Published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by

OXBOW BOOKS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford, OX4 1JE

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083

Historic England. Historic England thanks Oxbow Books for publishing this volume on their behalf.

Hardback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-449-9

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-450-5 (epub)

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ottaway, Patrick, author.

Title: Winchester : St. Swithun;s city of happiness and good fortune : an archaeological assessment / by Patrick Ottaway ; incorporating contributions from Tracy Matthews, Ken Qualmann, Stephen Teague and Richard Whinney.

Description: Oxford : Oxbow Books, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017000880 (print) | LCCN 2017001946 (ebook) | ISBN 9781785704499 (hardback) | ISBN 9781785704505 (epub) | ISBN 9781785704512 (mobi) | ISBN 9781785704529 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: Winchester (England)Antiquities. | Excavations (Archaeology)EnglandWinchester. | Winchester (England)History.

Classification: LCC DA690.W67 O88 2017 (print) | LCC DA690.W67 (ebook) | DDC 942.2/735dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017000880

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

Printed in the United Kingdom by Short Run Press

Typeset in India by Lapiz Digital Services, Chennai

For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact:

UNITED KINGDOM

Oxbow Books

Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449

Email:

www.oxbowbooks.com

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Oxbow Books

Telephone (800) 791-9354, Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate Group

This volume has been funded by Historic England (formerly English Heritage)

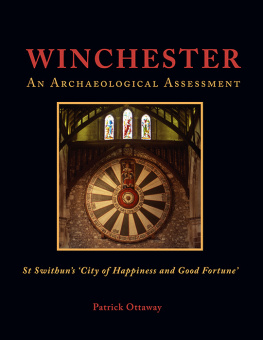

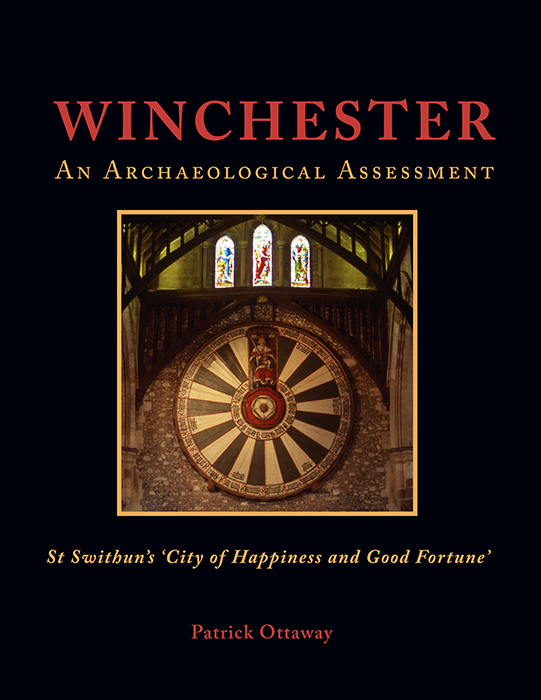

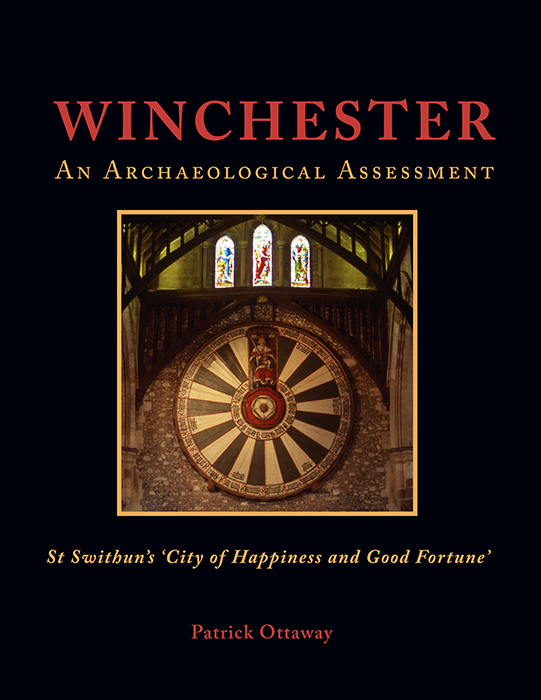

Front cover: The Winchester Round Table on the wall of the Castle Great Hall

Back cover: Winchester cathedral looking north-west

Contents

Foreword

The discovery of Roman and Saxon antiquities including a brick pavement of tesselated work found in digging the foundations of The Kings House for Charles II in 1683 is the first known record in the archaeology of Winchester. The end of the next century saw medieval discoveries at Hyde Abbey in 1788 and at the castle in 1797, and the first investigation the same year of the mortuary chests containing the remains of the Anglo-Saxon and Danish kings and bishops in the cathedral. In 1845 both the [Royal] Archaeological Institute and the [British] Archaeological Association held their (separate) second annual meetings in Winchester, publishing volumes which marked in several ways the beginning of archaeological enquiry in the city. During the rest of the 19th century newspapers often carried notices of the discovery of Roman mosaics and tessellated pavements, but it was only in 1926 that Sydney Ward-Evans took on the self-imposed duties of Winchesters Honorary Archaeologist beginning nearly two decades of watching hundreds of building sites and making up at his own expense information boards to which he attached pottery and other items for display in the new premises. The Hampshire Chronicle noted on his death in 1943 that he left no successor.

Winchesters museum, founded in 1846, had several homes and had been run by a succession of honorary curators. It was stagnating by 1947 when the City Council created the full-time post of curator, appointing Frank Cottrill. Apart from totally reorganising the museum and its displays, he drew on his experience excavating in London and Leicester and with dogged persistence carried out salvage investigations throughout the fifties. He also began the practice of bringing in younger archaeologists to run the first proper archaeological excavations in the city.

This was the context in which the city decided in 1961 that the site of a new hotel north of the cathedral should be extensively excavated. The following year the Winchester Excavations Committee was founded to undertake excavations, both in advance of building projects, and on sites not so threatened, aimed at studying the development of Winchester as a town from its earliest origins to the establishment of the modern city. The centre of interest is the city itself, not any one period of its past, nor any one part of its remains.

This was the beginning of urban archaeology. Ten seasons of excavation followed, from 1962 to 1971, on a scale never before attempted, carried out by volunteers from across the world working under experienced supervisors on sites throughout the city. In 1968, the Winchester Research Unit was set up, on a model developed for Polish towns, to study and present the results in a series of Winchester Studies published by Oxford University Press.

With the end of the Committees large excavations, the City established the post of Rescue Archaeologist, initially within the Research Unit but from 1977 within the City Museum. This important initiative led eventually led to the development of the Winchester Museum Archaeological Service. Most excavations on development sites within the city (and after 1974 in Winchester District), some on a large scale, as at The Brooks in 19878, were carried out by the Service until 2000, since when archaeological excavation and recording has been carried out by archaeological contractors funded under planning policy by developers. Today their operation is carried out under the eye of Tracy Matthews, Archaeological Officer of the City Council.

The work carried out under these different arrangements over the last 70 years forms the rich material upon which this Urban Archaeology Assessment is based. The extraordinary wealth of archaeological information recovered over these years is surveyed in detail in this comprehensive assessment. It might perhaps seem that we know an enormous amount about the origin and development of Winchester over the last two thousand years, so much indeed that there is very little need to go on digging, year by year, as each and every development site comes on stream.

Nothing could be further from the truth. At last we now have a base on which to ask questions which could not even have been posed 60 years ago. And some of these questions have only been clearly defined by the work of preparing this assessment.

Why was there a very large Iron Age enclosure on the western slopes of the present city covering an area of some 20 hectares and defended by a line of bank and ditch over 1.5km in length, representing a huge physical effort? What was its function and why was it abandoned sometime before 100 BC?

Why was the Roman town, Venta Belgarum , perhaps meaning something like The market of the Belgic people, provided with a substantial gated defence in the late 1st century AD, its interior laid out with a grid pattern of streets? And why were those defences reinforced at the end of the 2nd century, and again in the second half of the 3rd? And then in the 4th century apparently reinforced yet again by projecting stone bastions designed to carry catapults firing along the face of the wall from tower to tower? Was Venta at this time the base or one of the bases of the late Roman field army, the storehouse to which the tax in kind whether in sacks or on the hoof had to be delivered?

Next page