Owen Beattie is a professor of anthropology at the University of Alberta. He was born in Victoria, BC, and received his PhD from Simon Fraser University. He has contributed to many forensic investigations in Canada, as well as to human rights and humanitarian projects in Rwanda, Somalia, and Cyprus. He lives in Edmonton.

John Grigsby Geiger is St. Clair Balfour Fellow at Massey College, University of Toronto. He was born in Ithaca, New York, and graduated in history from the University of Alberta. His books have been translated into eight languages. He is a Fellow of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society.

First published in Great Britain by Bloomsbury in 1987

Copyright 1987, 1988, 1998, 2004, by Owen Beattie and John Geiger

This electronic edition published in 2012 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square,

London, WC1B 3DP

Published by arrangement with Greystone Books

(a division of Douglas & Mclntyre Ltd.), Canada

Introduction 2004 by O.W. Toad

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, Berlin, New York and Sydney

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

eISBN 9781408840849 (e-book)

www.johngeiger.co.uk

Visit www.bloomsbury.com to find out more about our authors and their books

You will find extracts, author interviews, author events and you can Sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers

For Shirley F. Keen.J.G.

For my first grandchild, A kasha (a.k.a. Pumpy)O.B.

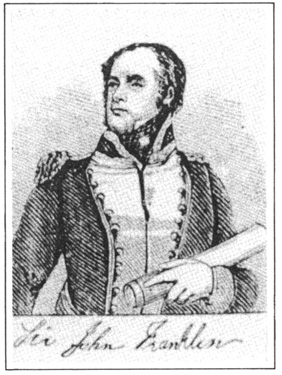

Frozen in time is one of those books that, having once entered our imaginations, refuse to go away. As Ive been writing this introduction, Ive described the project to several people. Frozen in Time, I say. They look blank. The one with the picture of the Frozen Franklin on the front, I say. Oh yes. That one, they say. I read that! And off we go on a discussion of forensic anthropology under extreme conditions. For Frozen in Time made a large impact, devoted as it was to the astonishing revelations made by Dr. Owen Beattieincluding the high probability that lead poisoning had contributed to the annihilation of the 1845 Franklin expedition.

I read Frozen in Time when it first came out. I looked at the pictures in it. They gave me nightmares. I incorporated story and pictures as a subtext and extended metaphor in a short story called The Age of Lead, published in a 1991 collection called Wilderness Tips. Then, some nine years later, during a boat trip in the Arctic, I met John Geiger, one of the authors of Frozen in Time. Not only had I read his book, he had read mine, and it had caused him to give further thought to lead as a factor in northern exploration and in unlucky nineteenth-century sea voyages in general.

Franklin, said Geiger, was the canary in the mine, though unrecognized as such at first: until the last years of the nineteenth century, crews on long voyages continued to be fatally sickened by the lead in tinned food. Geiger has included the results of his additional research in this expanded version of Frozen in Time. The nineteenth century, he said, was truly an age of lead. Thus do life and art intertwine.

BACK TO THE FOREGROUND. In the fall of 1984, a mesmerizing photograph grabbed attention in newspapers around the world. It showed a young man who looked neither fully dead nor entirely alive. He was dressed in archaic clothing and was surrounded by a casing of ice. The whites of his half-open eyes were tea-coloured. His forehead was dark blue. Despite the soothing and respectful adjectives applied to him by the authors of Frozen in Time, you would never have confused this man with a lad just drifting off to sleep. Instead he looked like a blend of Star Trek extraterrestrial and B-movie victim-of-a-curse: not someone youd want as your next-door neighbour, especially if the moon was full.

Every time we find the well-preserved body of someone who died long agoan Egyptian mummy, a freeze-dried Incan sacrifice, a leathery Scandinavian bog-person, the famous iceman of the European Alpstheres a similar fascination. Here is someone who has defied the general ashes-to-ashes, dust-to-dust rule, and who has remained recognizable as an individual human being long after most have turned to bone and earth. In the Middle Ages, unnatural results argued unnatural causes, and such a body would either have been revered as saintly or staked through the heart. In our age, try for rationality as we may, something of the horror classic lingers: the mummy walks, the vampire awakes. Its so difficult to believe that one who appears to be so nearly alive is not conscious of us. Surelywe feela being like this is a messenger. He has travelled through time, all the way from his age to our own, in order to tell us something we long to know.

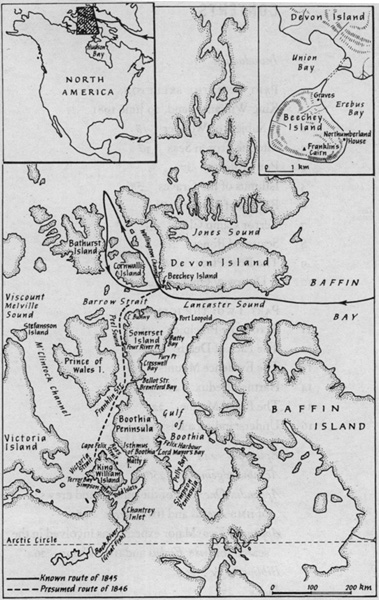

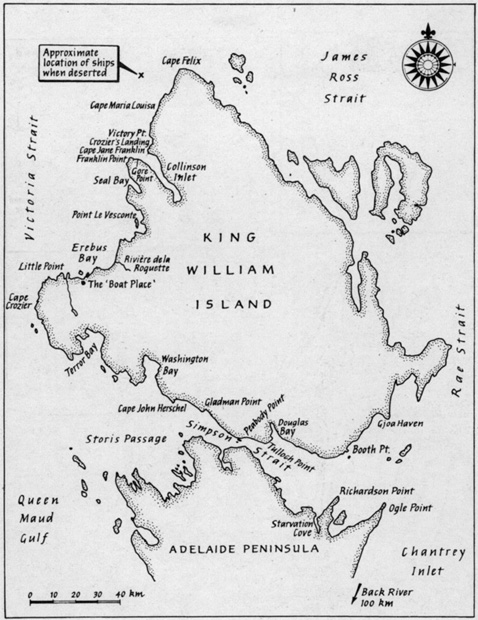

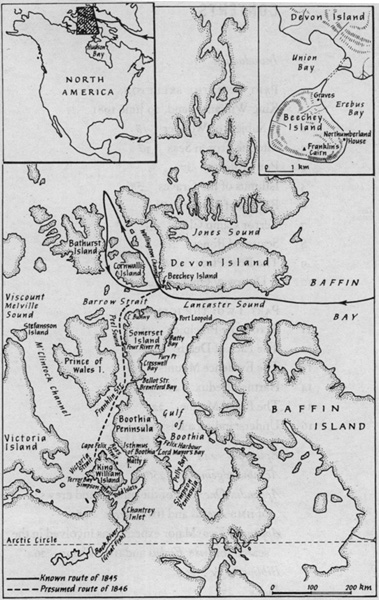

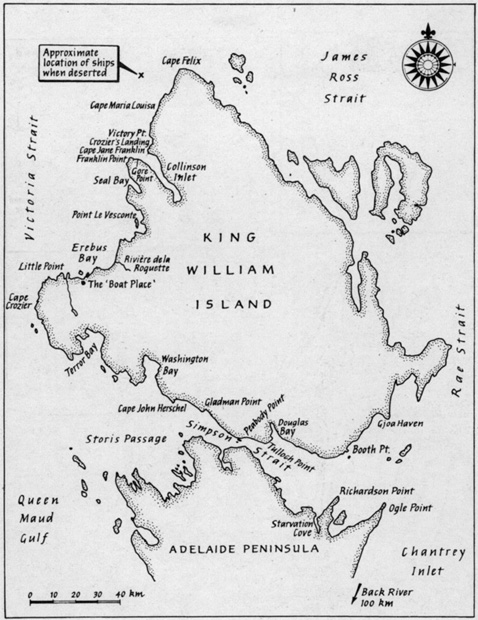

THE MAN IN the sensational photograph was John Torrington, one of the first three to die during the doomed Franklin expedition of 1845. The stated goal of the expedition was to discover the Northwest Passage to the Orient and claim it for Britain, the actual result was the obliteration of all participants. Torrington had been buried in a carefully dug grave, deep in the permafrost on the shore of Beechey Island, Franklins base during the expeditions first winter. Two othersJohn Hartnell and William Brainewere given adjacent graves. All three were painstakingly exhumed by anthropologist Owen Beattie and his team in an attempt to solve a long-standing mystery: Why had the Franklin expedition ended so disastrously?

Beatties search for evidence of the rest of the Franklin expedition, his excavation of the three known graves, and his subsequent discoveries, gave rise to a television documentary and thenthree years after the photograph first appearedto the book you are holding in your hands. That the story should generate such widespread interest 140 years after Franklin filled his fresh-water barrels at Stromness in the Orkney Islands before sailing off to his mysterious fate is a tribute to the extraordinary staying powers of the Franklin legend.

For many years the mysteriousness of that fate was the chief drawing card. At first, Franklins two ships, the ominously named Terror and Erebus, appeared to have vanished into nothingness. No trace could be found of them, even after the graves of Torrington, Hartnell and Braine had been found. There is something unnerving about people who cant be located, dead or alive. They upset our sense of spacesurely the missing ones have to be somewhere, but where? Among the ancient Greeks, the dead who had not been retrieved and given proper funeral ceremonies could not reach the Underworld; they lingered in the world of the living as restless ghosts. And so it is, still, with the disappeared: they haunt us. The Victorian age was especially prone to such hauntings, as witness Tennysons