Palgrave Studies in Pacific History

Series Editors

Matt Matsuda

Department of History, Rutgers University Department of History, New Brunswick, NJ, USA

Bronwen Douglas

College of Arts & Social Sciences, Australian National University College of Arts & Social Sciences, Acton, ACT, Australia

Palgrave Studies in Pacific History emphasizes the importance of histories of connection and interaction, with titles underscoring local cases with transnational reach. In dialogue with studies of the Pacific Rim focused on North American and East Asian relations, the series invites a rethinking of a Pacific globalized over many centuries through trans-regional encounters, networks, and exchanges. This "Oceanic" approach engages the Pacific Islands, Australia, maritime Southeast Asia, western Latin America, and parts of the Indian Ocean.

More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14605

Daniel Simpson

The Royal Navy in Indigenous Australia, 17951855

Maritime Encounters and British Museum Collections

1st ed. 2020

Logo of the publisher

Daniel Simpson

Department of History, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, UK

Palgrave Studies in Pacific History

ISBN 978-3-030-60096-9 e-ISBN 978-3-030-60097-6

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60097-6

The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

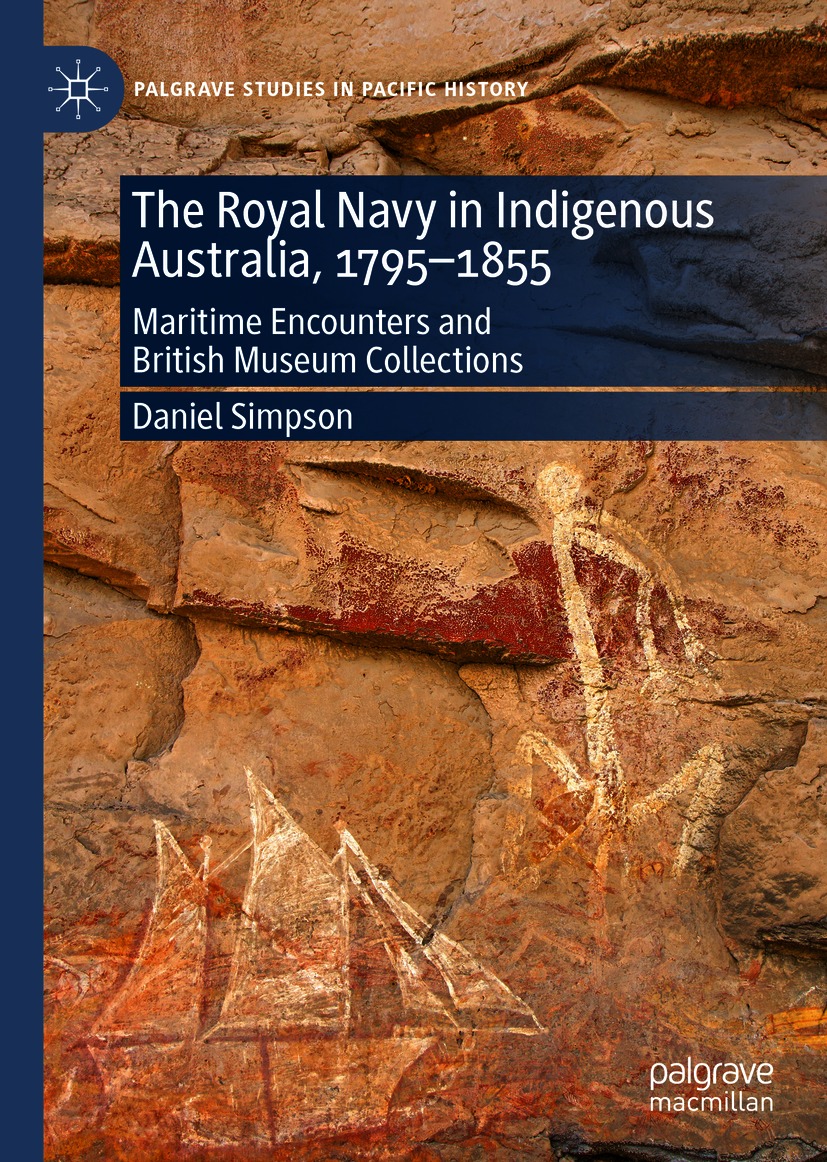

Cover illustration Andrew Bain / Alamy Stock Photo

This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

The registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland

For Hannah and Peter

Preface

Maritime encounters and exchanges shaped Indigenous Australians first contact with British naval explorers. In manifold and meaningful ways, they have never since ceased to mediate our colonial and postcolonial worlds. On the decks of ships, in sacred and ceremonial spaces, and through the galleries and storerooms of global museums, their legacy reverberates still. Formed in 2013, the Royal Australian Navys indigenous performance troupe, Bungaree, is an obvious and pertinent example of the continuities and complexities of an enduring relationshipone in large part forged between its famous namesake, a Kuring-gai man from the Broken Bay area north of Sydney, and the British Royal Navy captain Matthew Flinders, with whom Bungaree sailed as a friend and guide between 1798 and 1802.

Bungaree champions Indigenous Australian culture at special civic and ceremonial events; it offers performers and their supporters a home within the navy, and a forum for cultural expression. Composed of Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander sailors from throughout the continent, the dance troupe impresses its audiences with a lesson in Indigenous Australias considerable cultural diversity. This diversity was likewise soon appreciated by Flinders and successive naval explorers, who were by turns fascinated and bewildered by Bungaree and other intermediaries many travails as translators and cross-cultural brokers among peoples unfamiliar even to them.

Beneath the surface, deeper issues lurk. Bungarees performances express an uneasy coalition of history, aspiration, and political reality. With its customary military efficiency, Australias Department of Defence interprets the role of dance according to three primary objectives: to showcase Defence values and respect for Indigenous Australia, to reach out to potential recruits, and to engage with those Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander peoples who find themselves wary or uncertain of more conventional forms of reconciliation.

Entirely similar functions were attributed to dance in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century maritime encounters, at which aggressive or jocose performances communicated meanings and messages beyond the reach of words. In July 1838, two sailors from the expeditionary ship Beagle, then surveying Australia in the course of its third voyage, notably resorted to dancing for their lives after being surprised by an armed group of Woolna people at Escape Cliffs, in the modern-day Northern Territory. This absurd performancea very serious affairwas thereafter insisted upon by the Woolna people, on the not unreasonable basis that dancing sailors could not aim their rifles.

Elsewhere, performers danced through a similarly ambivalent atmosphere of merriment and tension. At the British Museum there now resides a Yadhaigana dance maskOc1851,0103.41collected in October 1849 at Cape York, in Far North Queensland, by the men of Owen Stanleys 18461850 Rattlesnake expedition. Though it now gazes blankly at museum shelves, the mask once surveyed a moonlit scene of cross-cultural confusion. Having encouraged and witnessed a night dance by Yadhaigana people, the Rattlesnakes men unwittingly insulted the performers by rewarding a local Queen, Baki, with a bagful of ships biscuit. This she then distributed to women and children who had merely spectated the event. The Rattlesnakes naturalist, John MacGillivray, gifted a detailed account of the hostility that ensued to future explorers, as a lesson in how a little want of judgment in the director of our party caused the most friendly intentions to be misconstrued, and might have led to fatal results.

I will return to Baki. In herself a rare example of a female presence in the navy and Indigenous Australias mutual encounters, she is also one of the very few named people with whom a surviving museum object can still be confidently associated: the Rattlesnake captains steward, Robert Gale, brought at least one basket belonging to her to England following the expeditions end. Altogether, the British Museum currently holds at least 135 such objectsall are just as resonant, and all were acquired in Australia by the Royal Navy in the course of its nineteenth-century expeditions. The purpose of this book is to echo the performative activism of