ISBN: 9789493056763 (ebook)

ISBN: 9789493056756 (paperback)

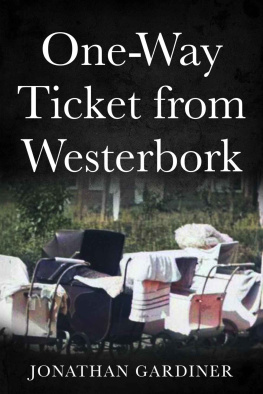

Cover: Prams left at Westerbork 1942-44 (Beeldbank WO2, NIOD, R. Breslauer?)

Copyright Jonathan Gardiner, 2021

Publisher: Amsterdam Publishers

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Foreword

This book is about the trains crossing between Westerbork in the Netherlands and other Nazi camps in German-occupied Europe, especially between October 1942 and September 1944. It was written for all those who took that journey not knowing whether it would be their last.

On a moor in the north of the Netherlands stood a camp that came to imprison many tens of thousands of Jews. Yet it was not the Nazis but the Dutch who built it. They did so to confine the many Germans and others seeking asylum in the Netherlands from a world in turmoil: Germany was systematically depriving Jews and others of their rights. Homosexuals, communists, Freemasons, Mormons and other minorities were being imprisoned or faced harsh penalties. The Netherlands, as a neighbour of Germany, began to receive more refugees than it could assimilate into Dutch society, so the government decided to build a refugee camp so people could be held until they could enter Dutch life.

Many German Jews also found themselves waiting in Westerbork. Today, it is a camp that few non-Dutch people will have heard of.

This is a story of the trains that left Westerbork and Amsterdam, heading east to the extermination camps in Poland and to Nazi concentration camps across Europe. It features material from diaries and Jewish sources that have recorded the histories of individuals and families. This story is chronological and does not contain footnotes. It brings together source material from Yad Vashem, the Joods Monument and first-hand diaries along with many reports and obscure papers not commonly used previously. It is not meant as a scholarly reference. All events are honestly recorded.

It is an indictment against those involved in perpetrating the Holocaust and against the Gentleman Kommandant of Westerbork who denied until his dying day that he had known the trains were transporting people to extermination camps this man who entertained Eichmann and associated with top Nazis when attending briefings about the Jewish Question.

I would like to extend my thanks to Dr Casey Hayes of Franklin College, Indiana (USA) for sparking my interest in Westerbork while I was researching the life of Willy Rosen.

Overview

I have come to know the last Kommandant of the Westerbork Transit Camp during the last few years. Some regarded him as a gentleman, whereas others took him for what he was a malicious, stone-faced smiling puppet master. Etty (Esther) Hillesum, a well-known Dutch diarist, saw through the faade of a gentleman. He might have played the gentleman, but as Etty wrote, it was a peculiar job for a gentleman to have. I have found him to be charming and well regarded by some, but those who saw beneath his veneer saw a man who was a deceitful and manipulative liar, although he liked to think of himself as cultured. You might ask why I would want to know such a man? Well the answer to that is simple: I do not. Would I profess to liking such a man? No, definitely not. Then how do I know him? I came to learn of him through someone whom, if I had known, I would gladly have called a friend. You must read further to see how this came about.

Obersturmfhrer Albert Konrad Gemmeker, SS number 382609, party member 5620430, was proud of the camp he ran. He went so far as to have it filmed and photographed in detail. Gemmeker knew he ran a model camp; his visitors came to watch the shows presented at the theatre he had built and to see his star-studded cast singing, dancing and telling jokes. There Gemmeker sat, in the front row, tapping his foot in time to the music, slapping the tops of his legs when a joke made him laugh. He would turn to his guests to see their enjoyment of the shows he staged for them. His guests, notes Philip Mechanicus, could be local Dutch farmers, ones who profited from the cheap camp labour and who sat alongside high-ranking SS officers.

Even Obersturmbannfhrer Adolf Eichmann laughed and took an interest in a dancing girl at Westerbork. Eichmann and Gemmeker discussed her at length after the show and again after Eichmann had met her. She was just another Jew to Gemmeker, so what did Gemmeker care that Eichmann took a liking to her? He would not question why. This just enhanced Gemmekers position. Others came from Amsterdam, guests of high-ranking Nazis, from all over, to be fted by Gemmeker who would show off his tame Jewish performers of film and the Berlin cabaret. This was how Gemmeker got through his day, seeking distractions from what he knew was his real task, transporting the Jews out of the Netherlands. What number had he been told? Some enormous number, enough to fill a city. One hundred and forty thousand Dutch, German and other nationalities currently residing in the Netherlands.

Albert Konrad Gemmeker from Dsseldorf had taken up his post on 12 October 1942 with the rank of Obersturmfhrer - Kommandant of the Polizeiliches Durchgangslager Westerbork. Those three squares set diagonally on his uniforms collar meant a great deal to him. His time in the police force at Duisburg and tedious Gestapo administrative work where he was diligent and regarded by superiors as reliable, had paid off. But a three-year wait to join the SS had seemed interminable. By November 1940, he was told that restrictions had been relaxed and was then admitted with the lowly rank of Hauptscharfhrer, the highest enlisted rank. He was already in The Hague working in the personnel department of the Sicherheitspolizei and the Sicherheitsdienst, the Security Police and Security Service. Not terribly exciting, he thought, but an opportunity arose to demonstrate his administrative skills. He was put in charge of the Sint-Michielsgestel internment camp in the south of the Netherlands in June 1942. While there, orders arrived to execute four hostages taken in retaliation for a Dutch Resistance attack on a German train full of soldiers headed home on leave. The bomb had exploded prematurely, injuring a Dutch railway worker. General Friedrich Christiansen personally issued the execution order.

Christiansen had ordered the arrest of 25 civilians who were also well-known in their communities. He demanded that the guilty persons give themselves up; otherwise, he would have the hostages shot. When the perpetrators did not turn themselves in, the general was forced to keep his word. Orders went out naming four, but then troops turned up with a fifth man. The action would serve two purposes. The men had double-barrelled surnames and, in German eyes, were therefore friends of Queen Wilhelmina who was safely in England. Executing them would send a message not only to insurgents but also to their Queen. Christiansen had not been in the Netherlands long, or he would have known that many Dutch had double family names. Two facts Gemmeker and other Nazis failed to grasp was that Queen Wilhelmina did not know any of these people and that the executions would make heroes of those executed. Others then vowed to avenge their murders, creating a circle of hate which would take years to break.