A HISTORY OF THE ROMAN WORLD FROM 30 B.C . TO A.D . 138

A HISTORY OF THE ROMAN WORLD

FROM 30 B.C . TO A.D . 138

BY

EDWARD T. SALMON

M.A., Ph.D., D.Litt., F.R.S.C., F.R.Hist.S.

MESSECAR PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, McMASTER UNIVERSITY, HAMILTON, ONTARIO

First published 30 November 1944

Second Edition 1950

Third Edition 1957

Reprinted 1959

Fourth Edition 1963

Fifth Edition 1966

Sixth Edition 1968

Reprinted 1970

Reprinted 1972

I.S.B.N. 0 415 04504 5

First published as a University Paperback 1968

Reprinted 1970

Reprinted 1972

Reprinted twice 1974

I.S.B.N. 0 415 04504 5

Reprinted 2004

By Routledge

11 New Fetter Lane, London, EC4P 4EE

Transferred to Digital Printing 2004

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

This title is available as both a hardbound and paperback edition. The paperback edition is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Preface to the Third Edition

TO discover that yet another reprinting of his work has become necessary is indeed a flattering experience for an author even when, as in the present instance, he knows full well that it is due to the fascination of the subject matter and not to any particular merits of his own. Besides affording gratification, however, it also imposes the obligation to introduce improvements wherever possible; and in the case of a reprinting as distinct from an entirely new edition this was bound to present some difficulties. For reasons of economy it was decided to reprint the present edition from plates cast from the text of the previous one, and this inevitably meant that any textual changes had to be contained within the pagination and indeed the lineation of the earlier edition. This, of course, imposed a limitation on the amount of alteration possible and necessarily involved rigorous compression and careful manipulation of language. I can only hope that in the process lucidity has not suffered, that an unjustified and certainly unintended dogmatism has not emerged and that the modifications of the text do not seem too awkward or too grotesque. For modifications there are, and the publishers have uncomplainingly and generously allowed them to be quite numerous. The attempt has been made not only to correct earlier mistakes and slips but also to bring the volume up to date with post-war work on the period with which it deals. The chapters on Augustus reorganization of the State, in particular, have been extensively revised; Appendix IV has been completely rewritten, and so has the Bibliography. I hope that, as a result, the work will be found more useful, although I do not expect to escape the reproach that my account of the various aspects of life in the first century and a half of the Roman Empire is rather thin. This is a single, not very large volume on a very large subject; and the constitutional and political, the social and economic, the military and the art historian will all no doubt find the treatment summary. I myself, for instance, greatly regret that the scale of the work does not permit a fuller account of the responsibility of the great families for the shaping and continuity of imperial policies. But in a book of modest size, which does not pretend to be anything more than an introduction to the history of the Early Empire, the temptation to go exhaustively into one topic at the expense of others had to be resisted as far as possible.

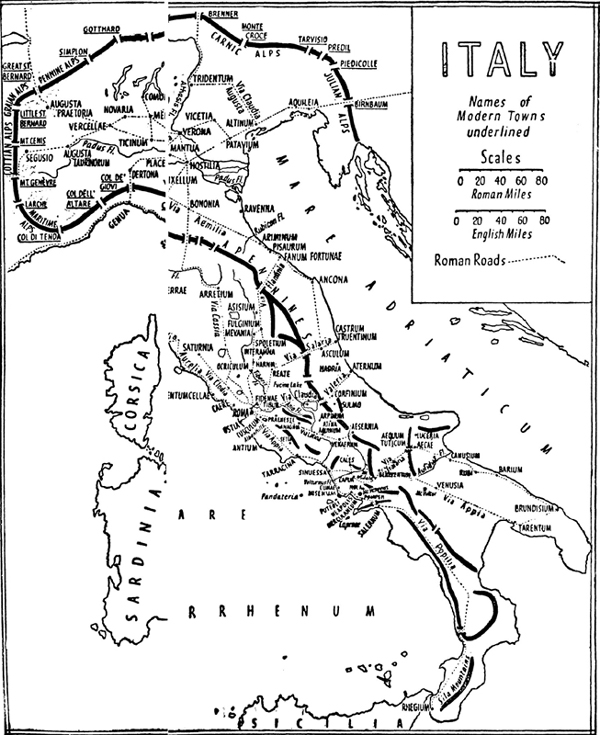

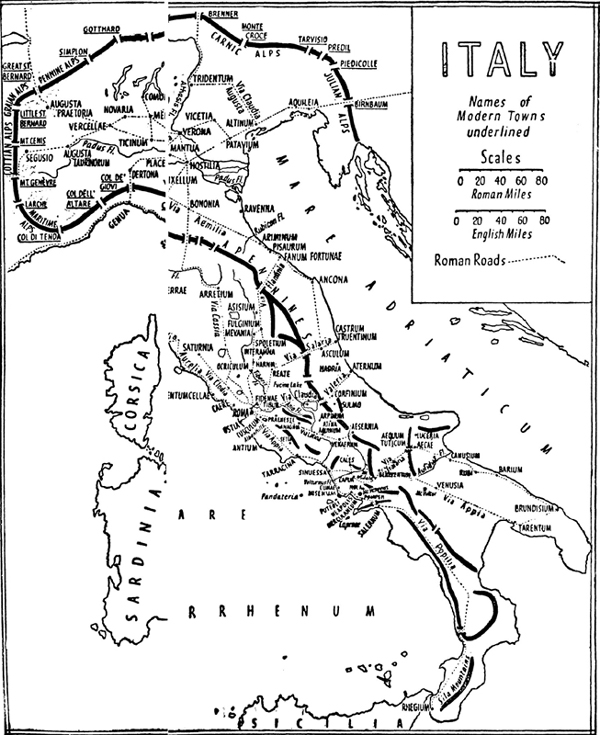

In general, the ancient names have been used except in cases where the modern name has become so familiar that to use any other would convey an impression of pedantry or might even confuse the reader. Thus, for Roman Britain the nomenclature adopted is the one most familiar to speakers of English.

Documentation has been reduced to a minimum in order to save space. It should not be taken to imply any reluctance on the authors part to acknowledge his obligations to his fellow-workers in the field. This book, in fact, makes no claim to originality: it merely seeks to provide a reasonably up-to-date synthesis of the history of the Early Empire. The bibliography will appear similarly sketchy: for it consists almost exclusively of books which have appeared recently, are likely to be available in most libraries, and are themselves well documented. From them the student desirous of consulting earlier works, and especially works in foreign languages, will be able to obtain all the information he requires.

Nowadays it is often fashionable to decry historical works in which individual personalities seem to be given undue attention; and some readers may regret that the framework of the present volume is the traditional one of the lives of the various Emperors. The following pages, however, will make it clear that the authors choice of this method is not due to any lack of interest in the life of the Roman world as a whole. The study of the Roman Empire has always exercised a marked fascination for citizens of its modern British analogue. This is particularly true in the case of one who received his early instruction in the subject at the great Australian University of Sydney, continued his studies at Cambridge, and is now a member of a Canadian University.

| E. T. Salmon, |

| Summer 1956 | H AMILTON , O NTARIO |

Preface to Sixth Edition

Recent work on the Roman Empire has dictated that a number of changes be made for this latest reprinting, which can accordingly be regarded as a new edition. The list of bibliographical items that has been added does not pretend to be complete. It does, however, direct attention to books where the interested student will find mention of most recent work of consequence.

CONTENTS

APPENDICES

I NDEX

MAPS

Part I

The Founding of the Principate

Chapter I

Augustus Princeps

1. The Restoration of Peace

THE previous volume has described how the Roman Republic failed. A period of confusion, unrest, civil strife and violence of all kinds had finally culminated in the emergence of one man as the supreme arbiter of the destinies of the Roman world. Octavian was now in a position to impose his will as he saw fit. The day of the Republic is done; the rule of the Caesars begins.

This failure of the Roman Republic was caused very largely by the reluctance of the Romans to change their methods of government and their political institutions generally. Conservatism and tenacity are no doubt valuable traits in a nations character; but conservatism may degenerate into mere obstinacy, and frequently obstinacy can be cured only by bloodshed.

The malady of the Roman Republic was caused by its attempt to govern a large Mediterranean empire with the political and administrative machinery of a city state. By means of various makeshifts and legal fictions the city on the banks of the Tiber did for a long time manage to administer the Empire with this inadequate political machinery. But ultimately the system broke down, and in the resulting anarchy Octavian fought his way to pre-eminence. His problem now was to settle the affairs of the Roman world and to place the Roman state once again on a stable basis.

Next page