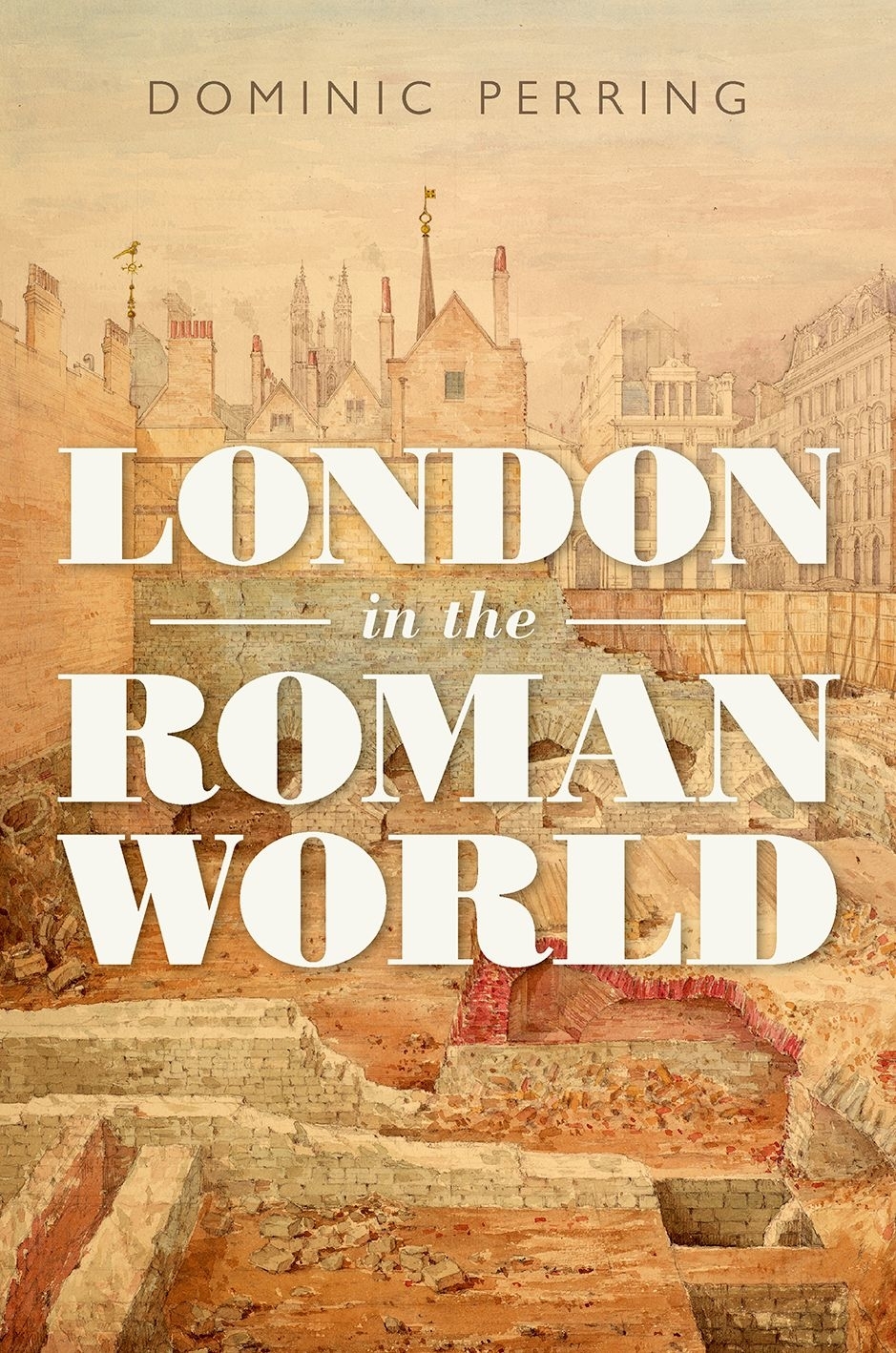

London in the Roman World

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Dominic Perring 2022

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2022

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021940826

ISBN 9780198789000

ebook ISBN 9780191093425

Printed and bound in the UK by

TJ Books Limited

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Preface

Acknowledgements

The writing of this book has stretched over the best part of a decade, following a very much longer period of interest in the archaeology of London. Throughout these years I have benefitted from the open generosity of numerous field archaeologists and specialists who have discussed their findings and ideas with me, and this leaves me a legion of magpie debts that I am unable to individually acknowledge: I am lucky to have been part of such an exciting research community. I am particularly grateful, however, to Gary Brown and Vicky Ridgeway for early sight of reports emerging from the investigations undertaken by Pre-Construct Archaeology, and to David Bowsher and Julian Hill for similarly keeping me abreast of work undertaken by the MoLA team. Ian Blair, Trevor Brigham, Gwladys Monteil, Rebecca Redfern, and Bruce Watson were all kind enough to give me early access to the unpublished results of their important research, whilst Damian Goodburn, Michael Marshall, and Jim Stevenson helped me to understand critical matters of detail in their replies to my questions. Andy Gardner, Martin Pitts, Louise Rayner, Jackie Keily, Sadie Watson, and Tim Williams read parts of this text in an earlier draft, and helped enormously with both thoughtful comment and encouragement. Dan Nesbitt kindly arranged access to materials and records held at the Museum of Londons Archaeological Archive, an exercise that was sadly curtailed by the interruptions of Covid-19 closure. I would never have found the time to write these words without the unstinting support of my colleagues at Archaeology South-East, who have accommodated my many distractions with this work, and it would never have reached print without a generous grant from the Marc Fitch Fund to cover the costs of preparing new illustrations by Justin Russell and Fiona Griffin. Justins diligent mapping of recent discoveries, in particular, has added enormously to my understanding of Londons archaeological landscape. I am also deeply grateful to the editorial team at Oxford University Press Charlotte Loveridge, Cline Louasli, and Juliet Gardner for steering this work to conclusion after its lengthy gestation. Most of all, however, I thank Rui and Zi for their love and forebearing throughout.

Navigating Londinium

Those unfamiliar with London are likely to find the Roman town difficult to navigate. There is no agreed system for naming and locating its ancient streets and houses, and modern place-names and postal addresses have changed with confusing frequency over the years. A proliferation of catalogues has served past surveys, each sensible to a different logic. Rather than add to this number I have followed the approach adopted by Richard Hingley in his recent study Londinium: A biography. This involves using the unique alpha-numeric excavation codes of the Guildhall Museum and Museum of London to identify individual excavation sites. These site-codes preserve the vital link between the primary archaeological record and the different interpretations and reconstructions that have been layered onto these observations. These sites are all listed and mapped in a concluding gazetteer ().

The maps of Roman London used to illustrate this account are necessarily highly schematic and involve a fair degree of conjecture. Those with a close interest in the urban topography may also find it useful to consult the fold-out 1:3000 scale map of Roman London published by the Museum of London. At the time of writing, this remains in print and obtainable from https://www.mola.org.uk/londinium-new-map-and-guide-roman-london. Although somewhat dated, it remains a splendid initial point of reference. A useful, if not entirely reliable, map of Londons Roman environs can also be found online at https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=9a85640effc042ae91af6b0d43abbafb.

The Museum of Londons Archaeological Archive remains the most valuable primary source, containing a wealth of unpublished information. This is a public archive where many of the finds and records described here can be consulted by prior arrangement. Some of the more important objects are also on public display: the British Museum draws heavily on the Roman London collection of Charles Roach Smith, and the Museum of London has long been committed to presenting the archaeological finds obtained from rescue excavations in and around London. The surviving remains of Londinium can also be visited, for which the City of London Archaeological Trusts online walking guide is highly recommended: https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/assets/roads-to-romewalk.pdf.

Contents

Points of departure

London is not only one of the worlds great modern cities but also, and perhaps more unexpectedly, one of its most intensely studied archaeological sites. Todays bright and glittering City, the square mile of high finance, perpetuates the site of a Roman town that commanded a strategic crossing of the river Thames. Excavations on City building sites fuel an archaeological research that continues to reveal new things about Londons Roman origins, offering rare insight into the empire of which it was part. These investigations explore a complex mound of rubbish that lifts todays streets some 9 metres above the virgin soil. The core of this study area is defined by the old towns walls, whose circuit can still be traced from place names and fragmentary ruins: extending from the Old Bailey in the west, past the Barbican, London Wall and Aldgate, to the Tower of London in the east. South of the river an archaeological landscape of equal complexity and no lesser antiquity, the outwork of Southwark, stretches back from London Bridge along Borough High Street to a point a little beyond the church of St George the Martyr. A dense hinterland of cemeteries, suburbs, and satellite sites surrounded these built-up areas either side of the river.