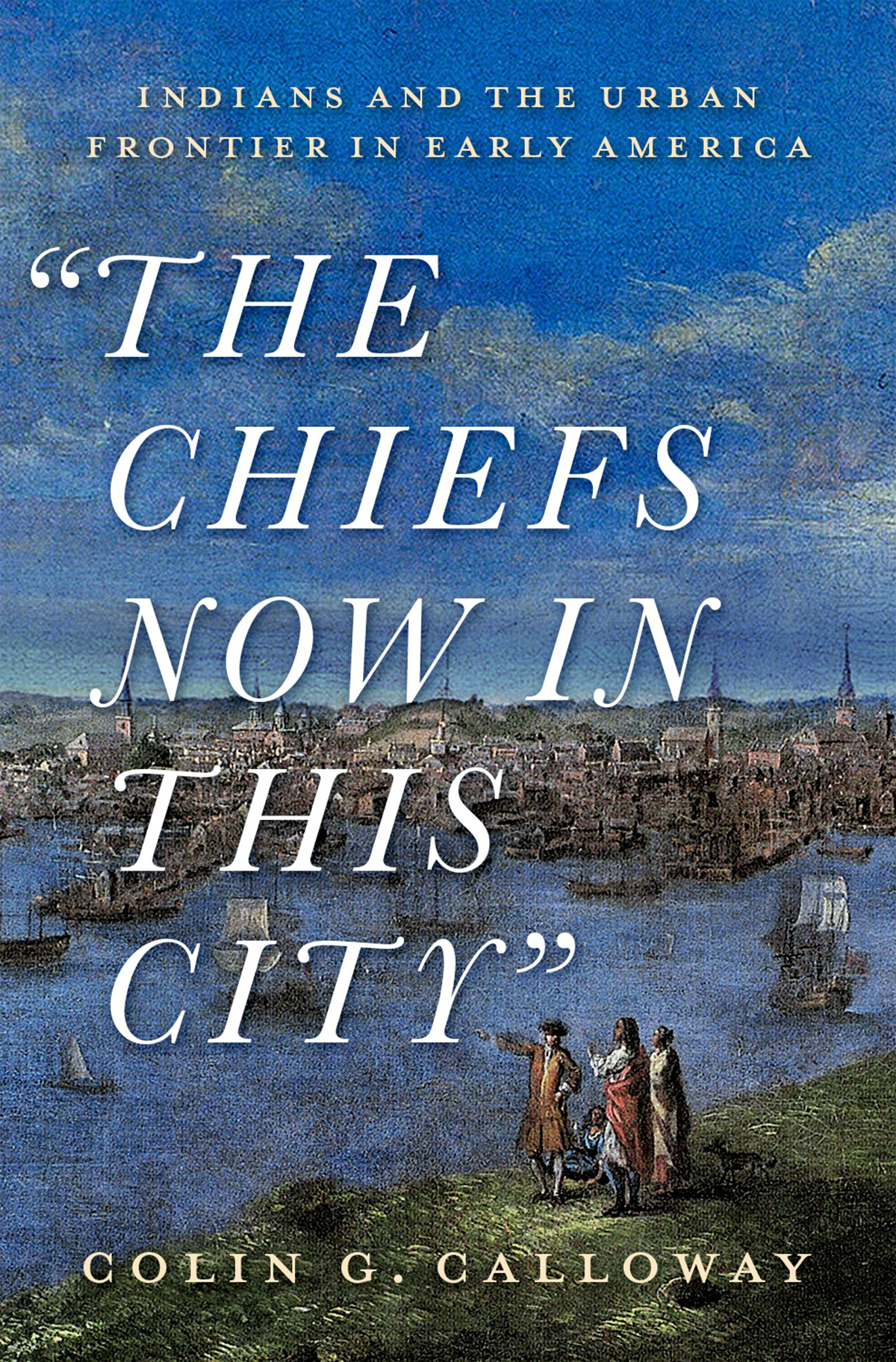

The Chiefs Now in This City

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780197547656

eISBN 9780197547670

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197547656.001.0001

To Marcia, Graeme, and Meg

Contents

Color plates

in the course of researching and writing two previous booksPen and Ink Witchcraft: Treaties and Treaty Making in American Indian History (2013) and The Indian World of George Washington: The First President, the First Americans, and the Birth of a Nation (2018)I became aware of a story I was not telling, and not even really seeing. Tribal leaders regularly traveled to early American cities, primarily on diplomatic business. Sometimes they went alone, more often they went in groups, and occasionally they brought a crowd. Cumulatively over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, hundreds of Indian people spent hundreds of days in cities. What did they do when they werent doing business, and what did they make of it all? The answers lie in the shadows of more fulsome descriptions of the negotiations they engaged in and the agreements they made, and piecing together glimpses of their other experiences has involved extensive needle-in-the-haystack research in government records, individuals journals and correspondence, and the surprisingly large number of newspapers of early America.

For her assistance in surveying newspapers, I am grateful to Sabena Allen (Tlingit), who worked with me on the project as a Presidential Scholar when she was an undergraduate at Dartmouth College. For assistance in retrieving and delivering multiple sources, I am grateful, as always, to my colleagues in Dartmouths Baker-Berry Library. For a congenial environment conducive to productivity, I am again thankful to my friends and colleagues in Native American Studies. Two anonymous readers who read parts of the manuscript in its raw, early stages offered generous advice and constructive suggestions. I am also grateful to Nathaniel Holly for sharing his dissertation with me as I finalized the manuscript, and to Mary Bilder for sharing an unpublished essay. At Oxford University Press, my editor, Timothy Bent, demonstrated sustained support, gave the manuscript thorough and thoughtful attention, and offered keen insights, and Amy Whitmer guided it expertly through production. Everyone involved in turning the manuscript into a book reinforced my conviction that when I publish with Oxford, I can take the highest standards for granted.

Colonial officials, observers, and the press routinely referred to tribal delegates as Indians and as the chiefs now in this city. In a book that has much to do with colonial perceptions and representations, I follow the sources in using Indians or Indian people, although I sometimes employ the terms Native and Indigenous as well.

Both chief and city are rather imprecise, generic terms that can have different definitions and connotations. Native American societies had many kinds of leaders who performed different roles in different circumstancesin war, peace, trade, council, ceremony, diplomacy, and the mediation of disputes within and between communitiesbut Europeans, and later the United States, applied the term chief loosely, with little understanding of how power was acquired and exercised. Although some individuals in this book are distinguished as sachems, sagamores, micos, war chiefs, civil chiefs, or spiritual leaders, for the most part, as in the colonial sources, chief is used as a term of convenience that embraces a variety of Indigenous leadership roles. Similarly, in dealing with colonial leadership, I have used the title governor throughout rather than make repeated distinctions between governor, lieutenant governor, and deputy governor.

Like chief, city (and town) can have various meanings, depending on time, place, perception, and purpose. Urban historians debate about what exactly constitutes a city. At one level a city is a large town, but cities were much smaller in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries than today, and in North America than in Europe and Asia, and official designations vary between, say, the United States and England, where for a long time city status was associated with having a cathedral. Expecting towns and cities to have institutions, stones, and structures, European colonists saw none in Native America. The cluster of communities at Kaskaskia at one point housed 20,000 inhabitants, a population no colonial city matched until the second half of the eighteenth century, but the French called it le grand village. Today, we often use city and town interchangeably. We may live on the outskirts of a city and go downtown to work or spend an evening out on the town. I follow the same practice.

The Chickasaw and Choctaw Indian Chiefs now in this City, will be present... this evening at the New Theatre.

Gazette of the United States, July 3, 1795

The Chiefs Now in This City

in the fall of 1784, Franois Marbois, secretary to the French legation to the newly independent United States, traveled to the country of the Oneida Indians, one of the Six Nations of the Iroquois league in upstate New York. He wanted to see the Indigenous peoples of the country firsthand and believed that time was short, for the advance of European population is extremely rapid in this continent, and since these nations live chiefly by hunting and fishing, they cannot remain in the neighborhood of cultivated regions. They go farther away, and soon it will be necessary to look for them beyond the Mississippi or even in the ice-covered regions around Hudson Bay. Ignoring the fact that Iroquois women had cultivated immense fields of corn, beans, and squash for centuriesand that American troops had destroyed forty Iroquois towns, 160,000 bushels of corn, and countless orchards in Iroquois country just five years beforeMarbois saw Oneida country as a wilderness. Traveling with his wife by horseback along Indian paths, he reflected on the transformations that civilization would surely bring to the landscape before him: