The University Press of Mississippi is the scholarly publishing agency of the Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning: Alcorn State University, Delta State University, Jackson State University, Mississippi State University, Mississippi University for Women, Mississippi Valley State University, University of Mississippi, and University of Southern Mississippi.

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of University Presses.

Text set in Warnock Pro and Hadriano Light

Material from : Balbancha was originally published in The Jazz Archivist, Vol. 28, 2015.

Copyright 2019 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Printed in China

First printing 2019

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

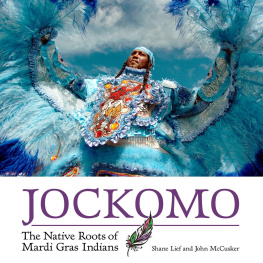

Names: Lief, Shane, 1971 author. | McCusker, John (John P.), 1963 author.

Title: Jockomo : the native roots of Mardi Gras Indians / Shane Lief and John McCusker.

Description: Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, [2019] | Material from : Balbancha was originally published in The Jazz Archivist, Vol. 28, 2015. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019008121 (print) | LCCN 2019020347 (ebook) | ISBN 9781496825919 (epub single) | ISBN 9781496825902 (epub institutional) | ISBN 9781496825926 (pdf single) | ISBN 9781496825933 (pdf institutional) | ISBN 9781496825896 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Mardi Gras IndiansHistory. | African AmericansLouisianaNew OrleansHistory.

Classification: LCC F380.N4 (ebook) | LCC F380.N4 L54 2019 (print) | DDC 976.3/35dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019008121

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you to the following people, who have offered intellectual companionship and loving feedback during the creation of this book:

First and foremost, Sarah Shelton, whose support has been manifold and well beyond words; Dona Lief, for unstinting enthusiasm in rallying the troops for public lectures; Tom Lief, with his inspiring commitment to Native cultural practices; Will Buckingham, sharing keen insights and courageously facing the maw of the academic meat grinder; John Joyce, always there with a sense of wonder; Russell Desmond, generous with his erudition; Cooper Wiley, for many enriching conversations; Jeffery Darensbourg, for sharing his experiences and leading the way to a deeper view; Lynn Abbott, Bruce Boyd Raeburn, Alaina W. Hebert, all three playing a key role in bringing our research to light; and also to so many others who have helped in various ways, including Pete Gregory, Daniel Usner, Kathleen DuVal, John Barbry, Donna Pierite, John Mayeux, James Andrew Whitaker, Kathryn Hobgood Ray, Nick Spitzer, Dan Sharp, Kyle DeCoste, Olanike Ola Orie, Judith Maxwell, Nathalie Dajko, Greg Waselkov, Greg Lambousy, Robert Sullivan, Luther Gray, Tosin Gbogi, Joshua Rogers, John DePriest, Evan Parker, and Jack Stewart, as well as other family members and friends.

For research assistance and support: Elizabeth McCusker, Ellen McCusker, Scott Aiges, Eliot Kamenitz, Kathy Anderson, Doug Parker, Lolis Eric Elie, Norman Dixon Sr., Alfred Bucket Carter, Belva Misshore Pichon, Joyce Montana, Katy Reckdahl, Natalie Pompilio, Chris Gray, Ashlye Keaton, Laura Paul, David Sager, Sherri Miller, and Joseph Makkos.

Mardi Gras Indians, both living and dead, who generously gave of their time, including Big Chiefs Robert Robbe Lee, Allison Tootie Montana, Victor Harris, Tyrone Casby, Clarence Delcour, Alphonse Dowee Robair, Estabon Peppy Eugene, Juan Pardo, Wallace Pardo, Walter Cook, Howard Miller, Al Womble, Kevin Goodman, Alfred Doucette, Cyril Iron Horse Green; and Queens, Flag Boys, Spy Boys, Wild Men, Drummers, and Needles, including Mercedes Merk Goodman, Dow Edwards, David Dejan, Ivory Holmes, Irving Scott, Issac Kinchen, Greggory Hawk, Thomas Bo Dean, Greg Perkins, Michael Green, Derrick Hullen, Thomas Watson, Darrell Lee Preston, Jay Williams, Jack Robinson, Irving Honey Bannister, Raymond Perique, Cherise Harrison-Nelson, and Ronald Lewis.

Finally, we offer thanks to all the people whose lives we wish to celebrate, recognizing our debt to those who came before us and who helped shape the world we inhabit.

Of course, any errors or lacunae in this book are our own responsibility. Nonetheless, we hope these will provide openings for future conversations.

PREFACE

We are all too aware of the contours of American history, which includes a long and bizarre record of attempts to capture a vanishing race of indigenous people or somehow encapsulate the spirit of a people or even the essence of Americahowever that may be imagined. There are notable examples of painters, photographers, and writers who have tried to do so. Although we also offer a collection of words and images, we do not claim that our book can fully represent any group of people or cultural tradition, and our work does not provide a conclusive statement about human nature. Instead, as a manifold of other peoples experiences as well as our own, recorded in various ways, this book gives a range of views about the past and present, and especially how language and music make the past alive in the present. Most of all, this book grows out of our love for our hometown of New Orleans. As the city marks three hundred years of existence, it is intrinsically worthwhile to ask questions about the meaning of this special place that has influenced so many lives. We find that the Mardi Gras Indian cultural system in New Orleans is a particularly compelling point of departure for asking such questions.

One of the peculiar aspects of New Orleans historiography is the relative absence of Native Americans from the story of the city. In the spirit of offering some balance in perspective, our story includes numerous encounters between indigenous people and others who came to this land later, as well as their descendants. Given the gaps in knowledge, many of which come from systematic erasures of people and public memory, we are confronted with the limits of language in discussing these many different cultural groups. Language usually fails to encapsulate the complexities of people, not only in terms of the intricate webs of family ties, but also in how people relate to others outside their kinship groups, and how everyone deals with others they might perceive as outsiders. The terms used in this story are themselves descendants of complex legacies of usage, and flow back and forth between Indian, Native American, indigenous group, and other expressions. Please note that, while White Mans Indian is an unequivocal reference to the way that Europeans and their descendants in North America have perceived Native Americans, the term Indian is also sometimes used in this sense. The particular history of that term alone is worth several volumes and is best discussed at another time and place. In the meantime, though, we believe it is good to continue exploring questions about the ambiguity of the word Indian, how this relates to New Orleans specifically, and what the more general implications are for all people and places.