mardi gras indians

LOUISIANA TRUE books tell the stories of the states iconic places, traditions, foods, and objects. Each book centers on one element of Louisianas culture, unpacking the myths, misconceptions, and historical realities behind everything that makes our state unique, from aboveground cemeteries to zydeco.

PREVIOUS BOOKS IN THE SERIES

Mardi Gras Beads

Brown Pelican

mardi gras indians

NIKESHA ELISE WILLIAMS

Louisiana State University Press

Baton Rouge

Published by Louisiana State University Press

lsupress.org

Copyright 2023 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved. Except in the case of brief quotations used in articles or reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any format or by any means without written permission of Louisiana State University Press.

LSU Press Paperback Original

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing

Designer: Barbara Neely Bourgoyne

Typeface: Source Sans Variable

Printer and binder: Integrated Books International (IBI)

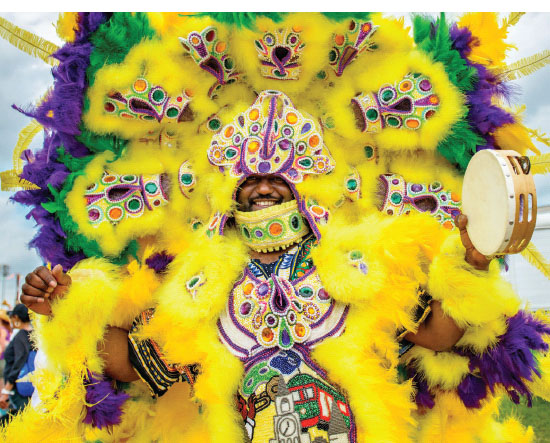

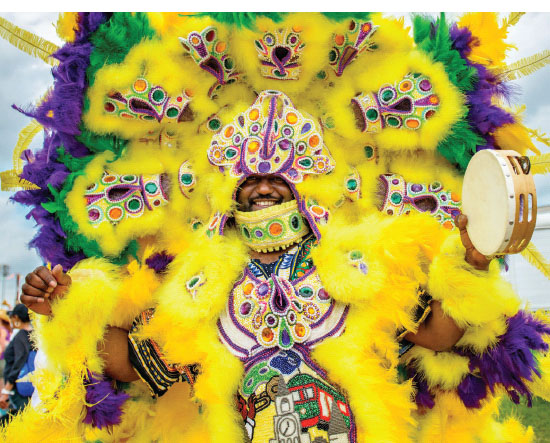

Cover illustration: Mardi Gras Indian at Jazz Fest, 2011 (modified). Courtesy Albert Herring, Tulane Public Relations / Wikimedia Commons.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Williams, Nikesha Elise, author.

Title: Mardi Gras Indians / Nikesha Elise Williams.

Other titles: Louisiana true.

Description: Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press, [2023] | Series: Louisiana true | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022014734 (print) | LCCN 2022014735 (ebook) | ISBN 978-0-8071-7870-6 (paperback) | ISBN 978-0-8071-7913-0 (pdf) | ISBN 978-0-8071-7912-3 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Mardi Gras IndiansSocial life and customs. | Mardi Gras IndiansHistory. | African AmericansLouisianaNew OrleansHistory.

Classification: LCC F380.B53 W55 2022 (print) | LCC F380.B53 (ebook) | DDC 976.3/3500496073dc23/eng/20220420

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022014734

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022014735

IN MEMORY OF BIG CHIEF KEELIAN BOYD

Also known as Big Chief Dump, who died on March 28, 2021, from heart failure. He was thirty-seven years old. Boyd was known as The Hat Man and The Hook Up man in the Indian tradition for the elaborate crowns he constructed, and for being able to put together suits for Indiansstill building, beading, and sewing until the very last moment. Boyd masked for twenty-three years. Courtesy Matthew Hinton.

contents

Wild Tchoupitoulas Indian gang masked for Carnival in 2018.

Courtesy Erroll Lebeau.

preface

Food is my love language. The first inklings of this text began with food, specifically with my love for New Orleansstyle red beans and rice. A personal essay I wrote about that dish led to me being contacted by LSU Press regarding their project of publishing books about different aspects of Louisiana culture. An unsolicited query in my inbox asked, Are you interested?

Of course, I responded.

However, I didnt want to write about food as I had done in other essays. I knew immediately that I wanted to write about the Indians, but I agreed to look at the list of subjects the Press wanted to cover before making a final decision. As a New Orleanian once removed, similar to how author and journalist Isabel Wilkerson referred to herself in her book The Warmth of Other Suns, I shared the list with my mother, a New Orleans native. She said, The only thing on this list I know I can help you with is the Indians.

Her statement in March 2020 solidified what I would be writing about. I began my preliminary research with Google. The search engine immediately spat back at me dozens of newspaper stories on Mardi Gras and COVID; the global pandemic was still in its nascent stages in the United States. When I started this search to write the book proposal, Ronald W. Lewis, the founder of the renowned Museum of Dance and Feathers, was still alive. By the time I finished the proposal and submitted it in early April, he had died. The news of his death led me deeper into my family, as Lewis was the uncle of my cousin, Brent Taylor.

As the news of my project spread through my family like hot gossip after Sunday service, my father, also a New Orleans native, as well as aunts and cousins all suggested names I should look up and people I should speak with. My fathers suggestion: You gotta watch the documentary Tooties Last Suit. Tootie was the prettiest Indian ever.

My aunt Mary Ryan said: My next-door neighbor Charmon, her nephew is a Big Chief; his name is Romeo. You gotta get in contact with him. Hes on Facebook.

Other names I wanted to follow up on were those I kept seeing in the results of my Google search: Bo Dollis and Donald Harrison. Though both men had already passed, their children were still carrying on the tradition.

From my home in Jacksonville, Florida, I planned a trip to New Orleans in the middle of a global pandemic. I set up visits to archives and made preliminary contact with Romeo, the Mardi Gras Indian Council, as well as the Backstreet Cultural Museum. I planned to wing the rest of it once I got on the ground in the city. My mother flew from Chicago to Florida. Then we drove the eight hours on I-10 from Jacksonville to New Orleans.

Once in the city, Stafford Agee came to my aunt Marys house in the Seventh Ward and interviewed with me in the basement. I contacted Bo Dollis Jr. via Instagram, and he agreed to let me interview him at his townhouse in the East. My cousin Tanya Devey put me in contact with Keelian Boyd, whom shed known for years. When I arrived at the home of his cousin Charles Duvernay, I interviewed them first before calling in their spouses.

Another cousin, LMaun Morris, introduced me to Ronnel Butler. It was while I was out with LMaun that I caught up with my cousin Brent at Ronald W. Lewiss home. Though his wife was still grieving and didnt want to interview with me, she and Brent did allow me to walk through the museum and take notes and pictures as I pleased. During this walk-through I met Gilbert Cosmo Dave. He, too, was still grieving the loss of his best friend, but he agreed to open his heart and speak to me about the culture and the tradition. While still at the House of Dance and Feathers, Romeo messaged me that he was finally ready to talk. My interview with Cherice Harrison-Nelson took place after my trip to New Orleans as she was busy during my time there and did not want to meet in person because of COVID precautions. At the time of my visit, she participated in the memorial service for the late Joe Jenkins.

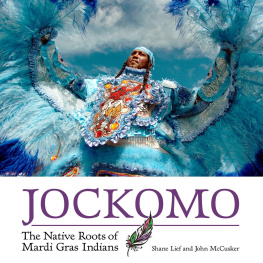

However, this cadre of interviews didnt provide me with enough material to write a book on a culture and tradition whose history spans centuries. During my visit to the Amistad Research Center, I was able to dig through the donated items from the Harrison family, many of which hadnt even been cataloged yet. It was there that I watched their family-produced documentary from the 1990s and received a link to watch the Maurice Martinez documentary from 1976. During my time digging through the archives at the Historic New Orleans Collection in the French Quarter, I returned to Google to find more primary sources. I ordered every book I could find. Jeroen Dewulfs From the Kingdom of Kongo to Congo Square; the biographies of Donald Harrison Sr. and Robert Nathaniel Lee by Al Kennedy; Jockomo: The Native Roots of Mardi Gras Indians, by Shane Lief and John McCusker; Congo Square in New Orleans, by Jerah Johnson, which I initially started reading in the archives; Freedoms Dance, with photographs by Eric Waters and narrative text by Karen Celestan; and Mardi Gras Indians, by Michael P. Smitha book so rare the first time I searched for it it was priced at $120. The secondhand copy I eventually purchased, with someone elses name scrawled in marker on the inside, still cost me $65. I also picked up Ronald W. Lewiss book published in conjunction with the Neighborhood Story Project during my jaunt with my cousin LMaun, and I ordered Victor Harriss book, also published with the Neighborhood Story Project months later.

Next page