Winner of the Jules and Frances Landry Award for 2017

NEW ORLEANS

CARNIVAL

BALLS

THE SECRET SIDE OF MARDI GRAS

1870-1920

JENNIFER ATKINS

LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS BATON ROUGE

Published by Louisiana State University Press

Copyright 2017 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

FIRST PRINTING

Designer: Barbara Neely Bourgoyne

Typeface: Adobe Garamond Pro

Printer and binder: Sheridan Printing

Portions of this book first appeared in Using the Bow and the Smile: New Orleans Mardi Gras Balls, Grand Marches, and Krewe Court Femininity, 18701920, Louisiana History 54 (2013): 546, and are used with permission of the editor.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Atkins, Jennifer, author.

Title: New Orleans carnival balls : the secret side of Mardi Gras, 18701920 / Jennifer Atkins.

Description: Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017009683| ISBN 978-0-8071-6756-4 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 978-0-8071-6757-1 (pdf) | ISBN 978-0-8071-6758-8 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: CarnivalLouisianaNew OrleansHistory. | Balls (Parties) LouisianaNew OrleansHistory. | Ballroom dancingLouisianaNew OrleansHistory. | Social classesLouisianaNew OrleansHistory.

Classification: LCC GT4211.N4 A75 2017 | DDC 394.269763/35dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017009683

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

For David

CONTENTS

ONE

Vive La Danse!

Balls and Mardi Gras in New Orleans History

TWO

A Most Brilliant Assembly

Preparing for the Ball and Choreographing Class

THREE

The Age of Chivalry Is Not Passed and Gone

Tableaux Vivants during Reconstruction

FOUR

A Strange and Silent Group

Courtly Grand Marches and Quadrilles

in the Gilded Age

FIVE

The Very Maddest Whirlpool of Pleasure

Ballroom Dancing in the Progressive Era

Table 2: Carnival Court Family Dynasties in Old-Line Krewes

and Tableaux Societies, 18701920

ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am indebted to many colleagues for their advice and support in the evolution of this book. Special thanks to Tricia Henry Young, Sally R. Sommer, Suzanne M. Sinke, Rachel Carrico, Shelley Manry Bourgeois, and Gianna Mercandetti, who provided insightful feedback at different stages of the manuscript. The biographical sketches compiled here would not be possible without the incredible sleuthing of Nikki Caruso. I am also grateful for the incredible assistance provided throughout the years by Lucy Escher Kahn, Anna Patsfall, and Bhumi Patel. Additionally, my archival experiences have been unparalleled, in great part because of the archivists, librarians, and curators who have guided me: Amy Baptist, Pamela Arceneaux, John Magill, and Rebecca Smith at the Historic New Orleans Collections Williams Research Center, as well as Leon Miller and Sean Benjamin at Tulane Universitys Louisiana Research Collection. Finally, thank you to my brainstorming krewe: Hannah Schwadron, Ilana Goldman, David Atkins, and the littlest onemy Rose. Each one of you has kept this book alive and moving forward. Thank you.

NEW ORLEANS

CARNIVAL

BALLS

Introduction

D uring New Orleans Mardi Gras festivities in the latter half of the nineteenth century, lavish balls were the culminating celebration of public parades for the oldest Carnival organizations, called old-line krewes. However, the Carnival balls (alternately known as bals masques) that immediately followed parading were also crucial krewe events. It was in the ballroom theater that krewe traditions and identities were reinforced. As members moved through carefully prescribed behaviors and dances, their tensions and reconciliations were formalized.

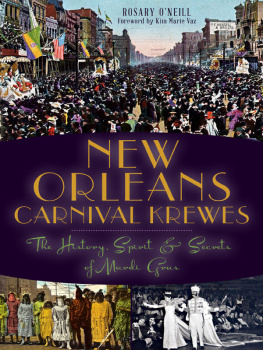

Old-line krewes were elite, white, all-male organizations (most established in the 1870s) dedicated to producing spectacular Mardi Gras celebrations consisting of a seasonal public parade, masking, and a private grand ball. The oldest, most prestigious clubsthe Mistick Krewe of Comus, the Krewe of Proteus, the Knights of Momus, the Twelfth Night Revelers (TNR), and the civic-minded Rexreigned over Mardi Gras. After the parades wound their way through New Orleans streets amid throngs of spectators, the krewesmen would enter the ballroom to spend the evening socializing, being entertained, and dancingthe zenith of krewe celebrations. Here women joined in the festivities as guests and participated as part of a mock royal court, complete with promenades and special dances. Krewesmen masked as utopian visions of themselves at the ball and carried with them the weight of their groups identity. These performances were for krewe eyes only. This was the secret side of Mardi Gras.

For old-line members, Mardi Gras rituals, especially private balls, conveyed significant information about their place in the world around them. To krewesmen, Carnival play was intensely serious. Not surprisingly, these men lost power in the ensuing Radical Republican government installed in Louisiana during Reconstruction. In attempts to reclaim a feeling of social status and dominance and to minimize the chaotic change they were experiencing, krewesmen retreated to the clandestine workings of their Carnival clubs. There they scripted a romantic image of the Old South, and in doing so, they drew on genteel mores while they masked as gods, kings, and modern-day knights.

The krewes ballroom signifies more than a place: It was also a ritual, a performative ceremony where complex social choreographies inscribed status, power, and identity. The manners and deportment that kept the ballroom running smoothly were distillations of socially constructed actions that translated cultural values into physical movements. Beautifully costumed krewe members executed rehearsed movements that displayed their elegance, body control, and command of appropriate codes of deportment, whether proceeding through a formal tableau presentation or dancing a popular quadrille (a European square dance that emphasized stateliness as dancers moved through interchangeable, geometric patterns). Ballroom protocol was dictated down to the smallest detailsan 1889 etiquette manual outlined eight distinct movements and seven shifts of body weight to properly perform a simple curtsy. Curtsies for women and bows for men were often part of salutations at a nineteenth-century ball and in social outings. They were, as William Greene wrote, the criteria of good breeding. For urbane New Orleanians, these choreographed and dancerly ballroom behaviors embodied and maintained important codes of civil behavior and reflected their perspectives about the world around them. The significance of these ballroom rituals is highlighted by an infamous dispute between two old-line krewes.

Mardi Gras night in 1890 was marked by conflict. The Mistick Krewe of Comus, New Orleans oldest Carnival organization, prepared for a glorious return to parading after a five-year hiatus.

When Mardi Gras night came, the Comus and Proteus parades happened to intersect on Canal Street, blocking both krewes from proceeding. Mardi Gras came to a standstill. Canal Street was an important marker delineating the American from the European sectors of the city, and it was the place where the most spectators gathered. On Canal, the parades went up one side of the street, crossed over the neutral ground (the New Orleans term for median), then paraded down the other side. From there, they turned off the busy public thoroughfare and disappeared into the French Quarter, the oldest area of the city where krewes staged their private Carnival balls. It was here, at the crossroads on Canal Street, where Comus and Proteus, in their determination to outstrip each other, turned the parade into an angry public standoff.