Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2014 by Rosary ONeill

All rights reserved

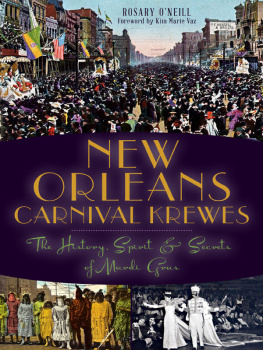

Front cover, top: Panoramic postcard of the Rex parade on Canal Street, 1904. John N. Teunisson.

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62584.609.9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ONeill, Rosary.

New Orleans Carnival krewes : the history, spirit and secrets of Mardi Gras / Rosary ONeill.

pages cm

Summary: Explore the secret past of Carnival krewes and the significance of the organizations in the history and culture of New Orleans-- Provided by publisher.

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-154-9 (paperback)

1. Carnival--Louisiana--New Orleans--History. 2. Associations, institutions, etc.--Louisiana--New Orleans--History. 3. Secret societies--Louisiana--New Orleans--History. 4. Social classes--Louisiana--New Orleans--History. 5. Political culture--Louisiana--New Orleans--History. 6. New Orleans (La.)--Social life and customs. 7. New Orleans (La.)--Social conditions. 8. New Orleans (La.)--Politics and government. I. Title.

GT4211.N4O54 2014

394.25090976335--dc23

2013047436

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For Bob

My love is like a red, red rose.

Contents

Foreword

Three guides to the mystery, fantasy, indulgences and political machinations of Mardi Gras in New Orleans are legendary: writer, preservationist and city publicist Mr. New Orleans, also known as Lyle Saxon; businessman and Old Crow advertiser and distributor Nathan Johnny King; and educator, band director and entrepreneur-turnedcarnival purveyor Mr. Mardi Gras, also known as Arthur Hardy.

In his fictional works, Lyle Saxon made readers feel that he was their personal escort to an exotic place. As they traveled with him across the page, the readers were lost in time and led to imagine the inhabitants of this intriguing city waiting to welcome them and reveal secret information for their amusement, amazement and delight. Saxon oversaw the writers and editors of the Depression eras Louisiana Writers Project who produced the New Orleans City Guide. The book covered every inch of the city, annotated the attractions and delivered it to readers with discretionary incomes to entice them to explore the hidden treasures of a magical land. Nathan King, an employee of F. Strauss and Son, a wholesale liquor dealer, researched, wrote and distributed annual guides to black carnival clubs showcasing their members and events. His devotion to Mardi Gras revelry was so intense that he made every ball in the black community, which could easily number several dozen. He was honored for his devotion by his election to serve as king of the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club parade in 1955. His scepter had a coconut (the signature throw of the club) at its base and an old crow at the apex. Arthur Hardy, publisher of the Arthur Hardy Mardi Gras Guide, has for over three decades offered a sightseers guide to the inner workings of krewes and their balls, parades and historical narratives. A tireless reporter of the festivities as they happen, he broadcasts on both television and radio, providing the soundtrack for the passing parades.

Rosary ONeill is a docent of a different background. Trained in the theater and performing arts, she begins her tour of Mardi Gras at its birthplace in pre-modern Europe. She reveals the way rulers used the theater forms of the triumphal entry into the city and court masques to cement their power and authority. Through her coverage of Mardi Grases past and present, she brings a perspective not often covered by other guides to Fat Tuesday customs: the continuing influence of the theater tradition of the Medieval period to the formation of early carnival customs in New Orleans and the persistence of these retentions to present-day practices, performances and productions. In so doing, she uncovers the psychology of cityits penchant for parties, pageants and self-glorification. It is as though New Orleanians were children thrown out of the Garden of Eden who have been seeking reentry ever since. Carnival allows for the illusion of riches and royalty as available to everyman and everywomanclose, yet so out of reach.

Born into the upper class of New Orleans, ONeill has been an eyewitness to the old-line krewes production of carnival and its privileges and exclusions. She exposes the underbelly of the old-line krewes whose aims were to perpetuate white male privilege and power. Because of their prominence on business, municipal and religious boards and councils and their commissions as citizen-kings, they could promote Mardi Gras to become an economic driver of the citys financial system, of which they could stand to benefit the most.

Limiting the idea of Mardi Gras to elite male krewes with parades casts doubt on the value of other carnival revelers. By consigning them to the margins as charming ancillary sidebars, the quest to shape the image of real Mardi Gras has been centered on krewe culture. The obvious aim is to publicly affirm their supremacy in both status and incomebut it is not only that. The discounting of others points to elite male anxieties about the masking practices of female and working-class groups. Rendering the carnival activities of non-elite white men as happening in dangerous parts of the city (i.e., black neighborhoods) or during insignificant times of the day, other revelers are characterized as being either violent or simply amusing.

The fact that members of other Mardi Gras traditions have remained hidden, invisible and outside the Mardi Gras economy has to do with the differences in their audience reach, their economic impact and the social status of their members. But most importantly, it allows for powerful groups to ignore, minimize and disavow the claims these groups make about themselves. One early response came from a group of black friends who decided to invent an imagined Africa to satirically confront an imagined Europe. About 1910, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club asserted its right to ridicule Rex, an elite male krewe. Zulu created a street tableau that acted out the racist images old-line krewes had been circulating for decades through their float themes and parading customs. Through its entry, Zulu was seemingly declaring, If you think our skin is black, we will make it blacker, and if you think we are savages, we will come from the river and invade the city. Promoting a view in which only old-line and parading krewes constitute real Mardi Gras is a way of disavowing the very humanity of those to whom they feel superior. They deny the desire of all people to be publicly adored, affirmed and celebrated or, simply put, to be the toast of the town. Today, Mardi Gras is officially kicked off on Twelfth Night at the old seat of city government, Gallier Hall, by the mayor and male krewes Rex and Zulu.

Even though krewes are now nominally racially integrated, social class continues to be a standard of evaluation between old-line elite mens parades, womens parades, black parades and the Mardi Gras day truck parades. Factors include whether the beads are new or recycled, whether the floats are built for that specific parade and its theme or loaned from a wealthier krewe, the quality of the construction of the floats and whether they were professionally designed or decorated by the riders themselves and the percentage of krewe members income spent on throws and costuming. Also obscured by a focus on male krewe masking are the enormous demands placed on the mens female relatives and partners to assist with costumes and arrange parties, favors and invitations to events.

Next page