Copyright 2021 by Joshua D. Rothman

Cover image copyright The Washington Post via Getty Images

Cover copyright 2021 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: April 2021

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rothman, Joshua D., author.

Title: The ledger and the chain : how domestic slave traders shaped America / Joshua D. Rothman.

Other titles: How domestic slave traders shaped America

Description: First Edition. | New York : Basic Books, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020038845 | ISBN 9781541616615 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781541616592 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Franklin and Armfield (Firm)History | Slave tradeUnited StatesHistory19th century. | Slave tradersMississippiNatchezHistory19th century. | Slave tradersVirginiaAlexandriaHistory19th century. | SlavesUnited StatesSocial conditions19th century. | SlaveryEconomic aspectsUnited States. | Franklin, Isaac, 17891846. | Armfield, John, 17971871. | Ballard, Rice C. (Rice Carter), 18001860.

Classification: LCC E442 .R68 2021 | DDC 306.3/620973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020038845

ISBNs: 978-1-5416-1661-5 (hardcover), 978-1-5416-1659-2 (ebook)

E3-20210327-JV-NF-ORI

PRAISE FOR

THE LEDGER AND THE CHAIN

Antebellum America was simultaneously a robust marketplace of strivers and a landscape of horror for the millions who were enslaved. In this groundbreaking work, Joshua Rothman reveals the intimate connection between the two. His study of the under-examined slave trade shows how it was integral to the rise of interstate commerce, the flow of credit, and the establishment of new transportation routes. He also underscores its systematic cruelty, in which men gloried in rape and casually sold children from parents yet stood as respected members of the community. The Ledger and the Chain is detailed, incisive, and devastating.

T. J. S TILES , Pulitzer Prizewinning author of The First Tycoon and Custers Trials

The story of the international slave trade is well known to many. Much less known are the workings of the domestic slave trade in the United States that sent scores of enslaved African Americans from the Upper South to the cotton and sugar fields in the Deep South. With exhaustive research and piercing insight, Joshua Rothmans The Ledger and the Chain brings that history alive through the stories of three men who sat at the nexus between Southern cotton producers and Northern financial institutions. As the tragic legacies of these men are still with us, this book should be read by all who are interested in our current racial predicament.

A NNETTE G ORDON- R EED, coauthor of Most Blessed of the Patriarchs

We are sometimes told that the quintessential American story is the tale of the small business that makes it big. If thats the case, theres no more American story than The Ledger and the Chain, Joshua Rothmans brilliant new history of the slave-trading entrepreneurs Isaac Franklin, John Armfield, and Rice Ballard.

E DWARD E. B APTIST , author of The Half Has Never Been Told

Joshua Rothman carefully and empirically builds from a forensic accounting of the lives and practices of those Frederick Douglass termed the man-drovers and others called the soul drivers to a social autopsy of the whole of American slavery in the nineteenth century. Essential.

W ALTER J OHNSON, author of The Broken Heart of America

Flush Times and Fever Dreams: A Story of Capitalism and Slavery in the Age of Jackson

Notorious in the Neighborhood: Sex and Families across the Color Line in Virginia, 17871861

For My Children

You know what is a swine-drover? I will show you a man-drover. They inhabit all our Southern States. They perambulate the country, and crowd the highways of the nation, with droves of human stock. You will see one of these human flesh-jobbers, armed with pistol, whip and bowie-knife, driving a company of a hundred men, women, and children, from the Potomac to the slave market at New Orleans.

Frederick Douglass, What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?

To see the wives and husbands part,

The children scream, they grieve my heart;

We are sold to Louisiana,

Come and go along with me.

Go and sound the jubilee, &c.

The Poor Slaves Own Song

But who, sir, makes the trader? Who is most to blame?

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Toms Cabin

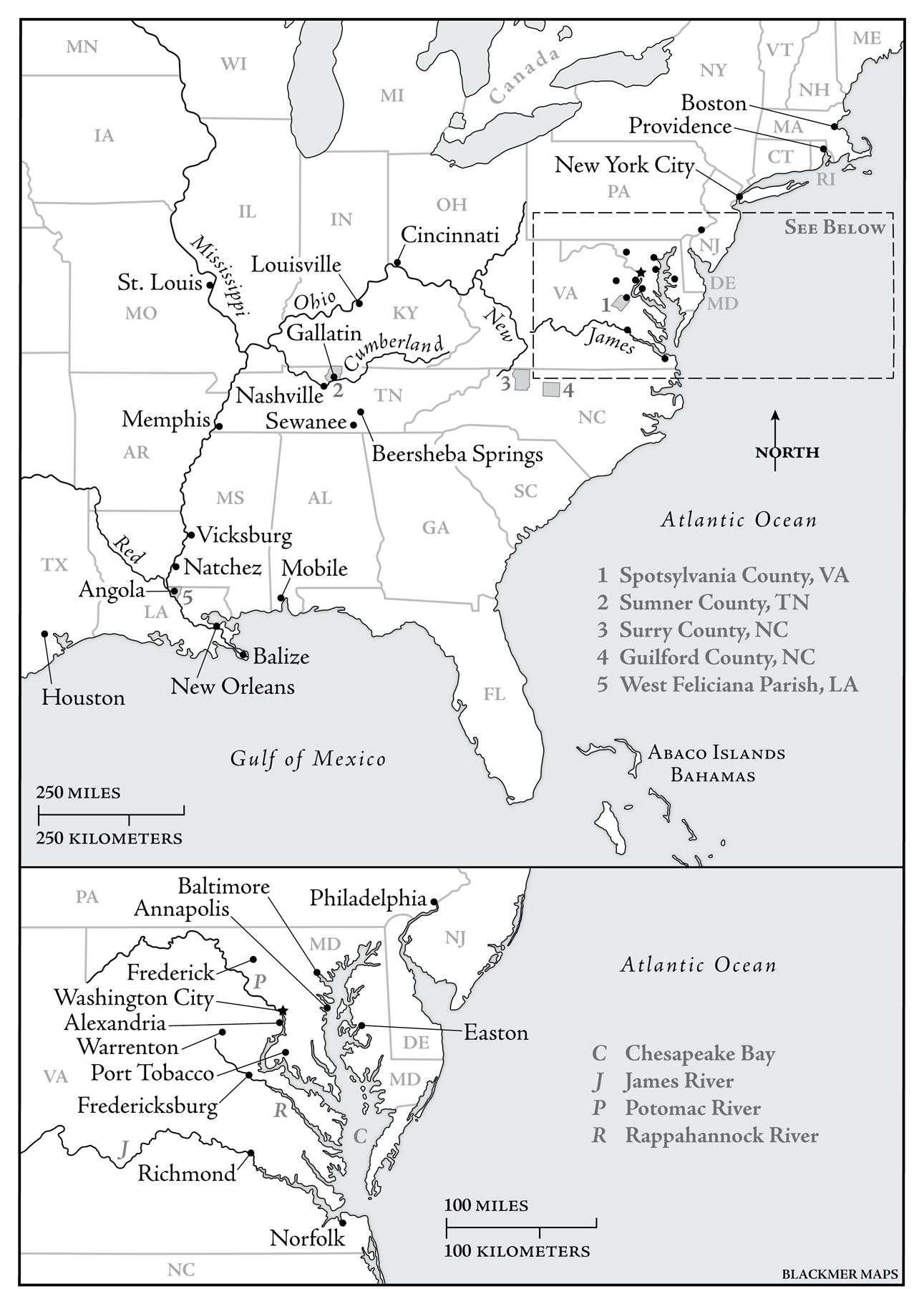

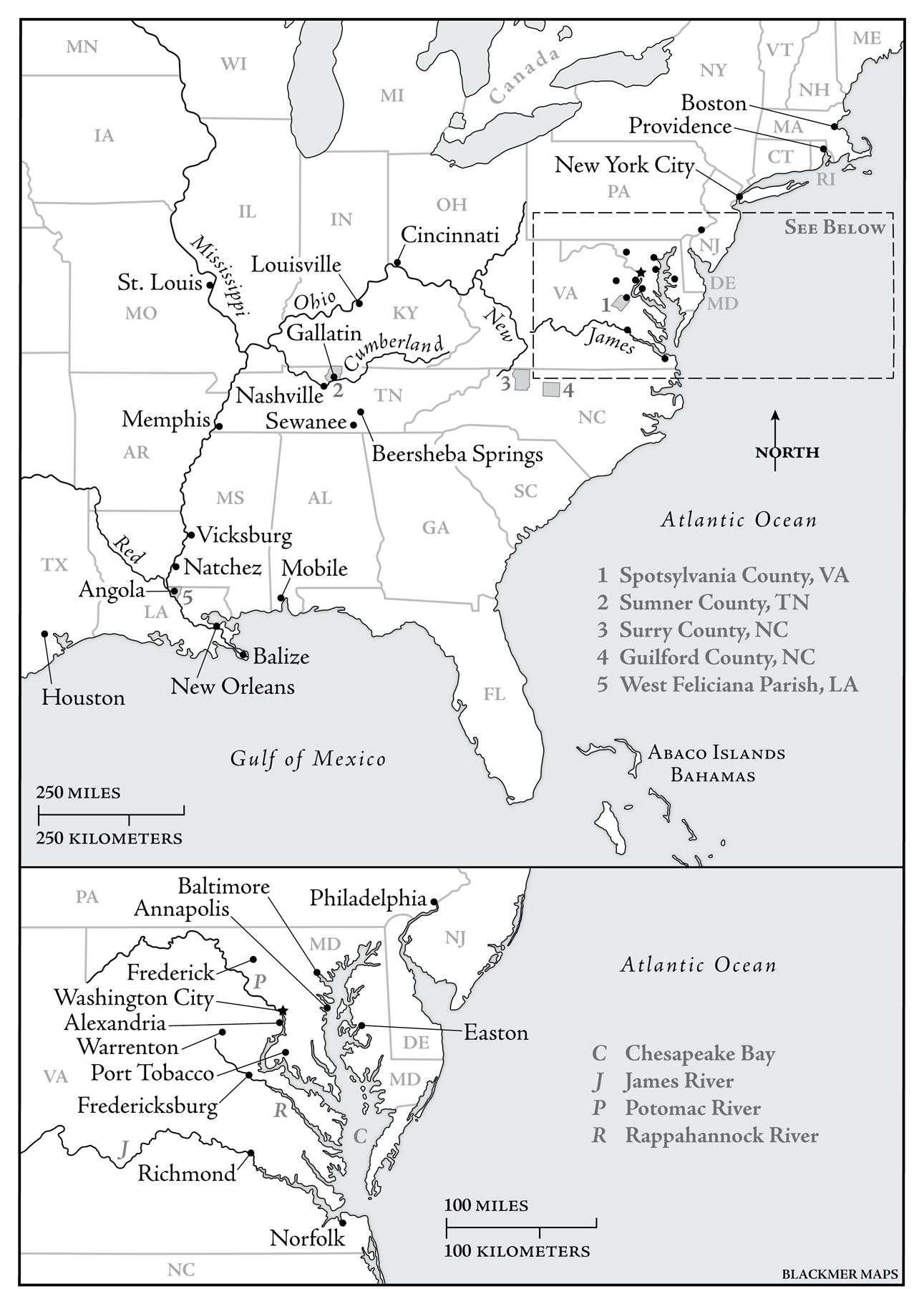

The slave-trading world of Isaac Franklin, John Armfield, and Rice Ballard.

T HE BODIES WERE PILING UP AND I SAAC F RANKLIN KNEW HE had to get rid of them. It was bad enough that every enslaved person who succumbed to cholera was a total loss to the company. If word spread in and around the river port of Natchez, Mississippi, that people in Franklins pen were dying, customers might not even buy the healthy ones. John Armfield and Rice Ballard kept shipping Franklin slaves from Virginia, but in December 1832, Franklin told his partners that in the preceding two weeks alone, disease had claimed the lives of more than fifteen of the captives they had sent. The death toll included half a dozen children, and Franklin had seven or eight others on hand who were vomiting, cramping, and experiencing uncontrollable diarrhea, their sunken eyes and cold, dry, inelastic skin telltale signs that they too might die.

A man concerned about the dignity of the enslaved might have arranged for proper burials. Isaac Franklin was not that man. Dead slaves brought no profit and threatened future gains. They were useless. So Franklin and an assistant waited till nightfall, tossed the

When winter turned to spring, light rain partially uncovered a teenage girl, a woman, and an infant, barely concealed beneath the soil. Further investigation unearthed still more decomposing bodies, a scene so grisly that a second set of jurors finished the coroners inquest after the first set was too revolted to complete the task. The dead were all wearing clothing identifying them as Franklins property, and his disposal scheme came undone. For a long while, the fact that slave traders operated in Natchez had unsettled some people, who thought it reflected poorly on the morals of the city and endangered public health and white lives. The discovery that Franklin had been dumping diseased human remains made the opinion nearly general. Horrified and outraged, white residents of Natchez circulated petitions, packed a public meeting at the courthouse, and clamored for action when the board of selectmen convened in emergency session. In April 1833, surrounded by an unusually large crowd and amid loud and continuous applause, the board banned slave traders from displaying slaves for sale within city limits.