The right of Nick Cooper to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in 10pt on 12pt Sabon.

Typesetting and Origination by Amberley Publishing.

Printed in the UK.

Tunnel vision a section of newly constructed Tube on the Piccadilly Line.

CHAPTER 1

BEGINNINGS

The London Underground was born of necessity. By the mid-nineteenth century the major railway companies had linked most parts of the country to London, but were prevented from venturing to the very heart of the city by Act of Parliament in the north and by high land prices north of the Thames in the south. Various railway companies had either sole possession or shared use of eleven mainline termini ringed around the capital, all desperate to project their lines further, both to link up with each other and, more importantly, to reach the ancient City of London, the financial powerhouse of the expanding Empire.

The only station actually within the boundary of the City was Fenchurch Street in the south-east, while to the north-east Bishopsgate lay just outside the border. To the north-west, Kings Cross was about a mile and half from the edge of the City and Euston further still; London Bridge was on the other side of the Thames, close to the south bank of the river. The upshot of all this was that traffic both human and freight could go no further than these stations and instead had to transfer to the overloaded road network, which was clogged with horse-drawn cabs, coaches, omnibuses and carts.

One City commuter who found this situation intolerable was a solicitor, Charles Pearson. But he had a solution; if trains could not run into the City on the surface, then why not under it? Finding willing investors in both the City of London Corporation and the Great Western Railway Company (GWR), the North Metropolitan Railway Company was incorporated in 1853 with the intention of constructing a three-and-a-half-mile underground railway between the planned GWR terminus at Paddington and a new station at Farringdon Street, on the north-east edge of the City boundary. In between there would be five intermediate stations, including ones at Gower Street (Euston) and Kings Cross.

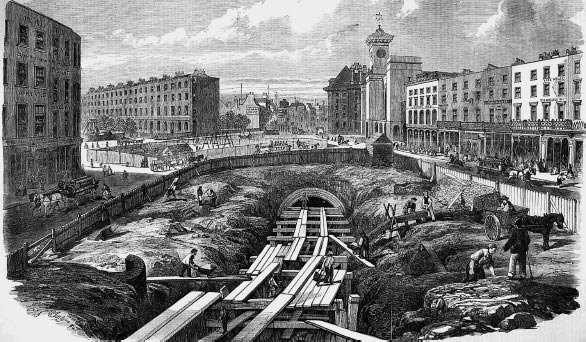

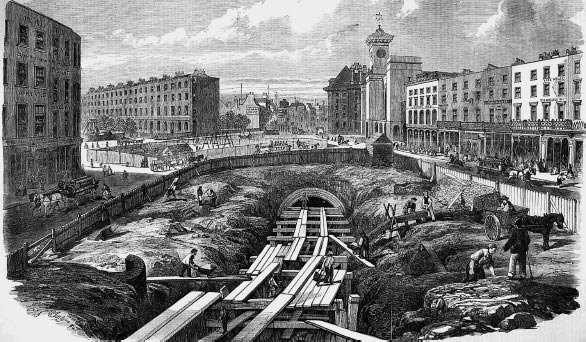

Unfortunately, the easiest and cheapest way to construct the railway was also the most disruptive. To avoid the cost of demolishing buildings, roughly half of the line west of Gower Street station ran as much under existing roads as possible, using a method of construction that became known as cut-and-cover. A deep wide trench was dug down the middle of the road, the brick tunnel built at the bottom of it, covered over again and the road re-laid. East of Gower Street, the line would be mostly in open cuttings. This was no bad thing given that the only motive power available was steam, so even the cut-and-cover sections needed frequent gaps to allow the smoke and fumes to escape.

Cut-and-cover sub-surface construction of the Metropolitan line passing Kings Cross in 1861. (JC)

The line was ready by the end of 1862 and after the customary inspection and approval by the Board of Trade and a few days of trial working, the Metropolitan Railway opened for passenger traffic on Saturday 10 January 1863. The opening had been celebrated the previous Friday, but one conspicuously absent guest was Charles Pearson, who did not live to see his dream of an underground railway become reality, having died just four months previously.

Short though the original section of the Metropolitan was, by the end of 1864 it had been extended westward and then south to both South Kensington and Hammersmith, with a branch off the latter to Kensington (Addison Road). The following year saw an eastern extension to Moorgate Street and by the end of the decade a branch at Baker Street was making a tentative move into the north-western suburbs, reaching Swiss Cottage. To the south, the Metropolitan District Railway had opened between West Brompton and Blackfriars stations, with a link to the Metropolitan line proper at Brompton Road.

The rapid expansion of these sub-surface lines continued over the next twenty years until, by 1890, they had between them reached as far south as Wimbledon and Richmond, west to Hounslow and Ealing (from which a service to Windsor lasted two-and-a-half years before proving a bit too far) and north to Chesham. In the east, the acquisition and re-purposing of the pedestrian Thames Tunnel it was the first tunnel in the world built under a wide river took both Metropolitan and District trains to New Cross. These extensions ran almost exclusively on the surface, since tunnels were not necessary further out where land was cheaper, but 1890 saw the arrival of a new player using a very different method of tunnelling.

In the mid-1860s, the engineer James Barlow developed a simplified variation of Marc Brunels huge rectangular tunnelling shield, which had been used to construct the Thames Tunnel between 1825 and 1843. Rather than a brick tunnel, Barlows would be composed of a series of 8-foot diameter rings formed from prefabricated curved cast iron segments, creating a continuous metal tube in which the track-bed would be laid; larger tubes would form the stations. When assembled, the outside diameter of the tunnels was slightly smaller than the circular tunnelling shield, so that the gap could be filled and sealed with liquid cement. This method of tube construction although much refined and now largely automated remains in use to this day.

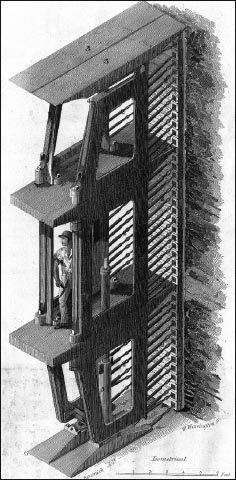

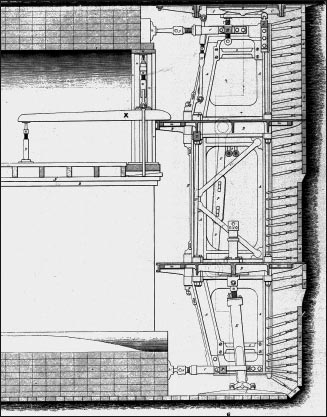

Although Barlow could not raise enough interest in a full railway, he tried out the basic principles by building a subway under the Thames between Tower Hill and Southwark where there was no bridge at that time with himself as engineer and his pupil James Henry Greathead as contractor. At each end of the tunnel there was a steam-powered lift to carry passengers 50 feet down to, or up from, the single 10-foot-long car that ran from one side of the river to the other on 2-foot 6-inch gauge track. Steam-powered cable haulage was used to move the car.