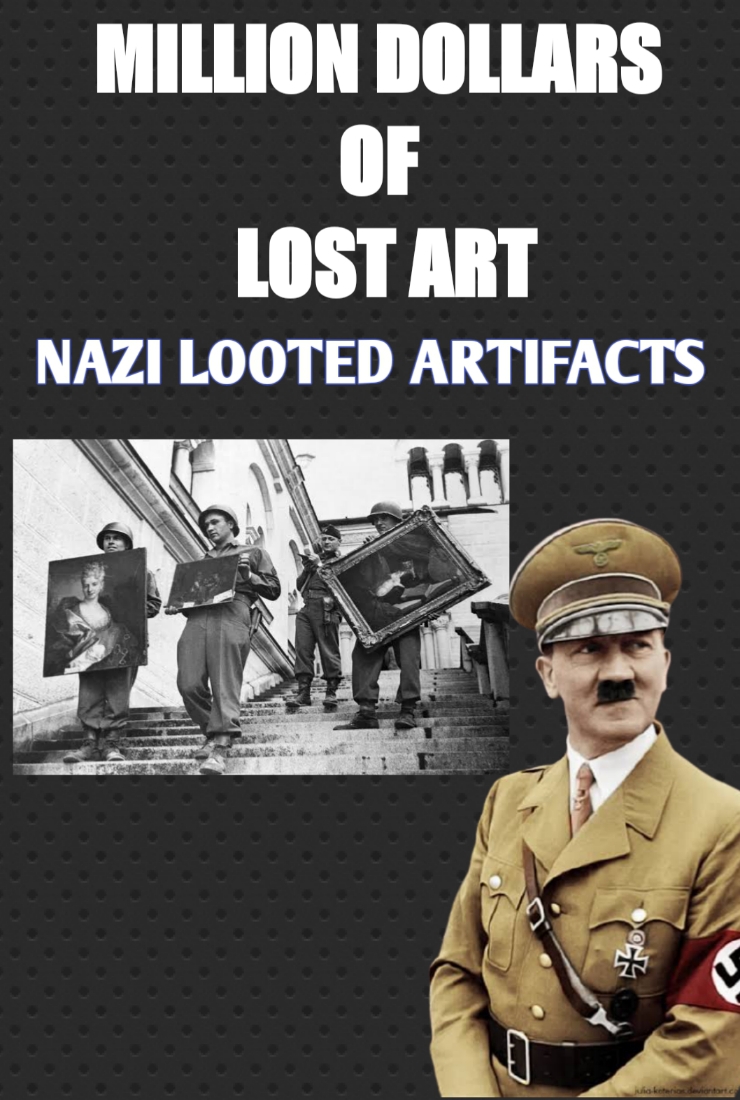

NAZI-LOOTED ART:

Paris Tribunal de Grande Instance held that the painting La Cueillette des Pois (Pea Harvest) by Camille Pissarro should be returned to the grandson of the Jewish art collector Simon Bauer whose collection had been confiscated by the Vichy Government in 1943.1 The American couple who sent the painting on a short-term loan to a Paris museum had acquired it at Christies in New York in 1995, reportedly for $800,000.2 Their disconte nt with the outcome and intention to appeal the verdict was voiced as:

It surely is not up to [us] to compensate Jewish families for the crimes of the Holocaust.

The claimants on the other hand welcomed the verdict as pure justice:

I think the French court has applied the natural law.3

Some months earlier, in July 2017, the City of Munich informed the public that a just and fair solution had been found regarding Paul Klees Sumpflegende (Swamp Legend), seized by the Nazis as degenerate art.4 The painting had changed hands several times by the time it was acquired for the Munich Lehnbachmuseum from a Swiss dealer in 1982. The press release informed the public that an undisclosed amount of money had been paid to the original owners to end decades of legal battle after a German court had earlier found that the claim was inadmissible. Shortly before that, litigation was initiated in the US over a painting by Kandinsky in the same museum following allegations that it was Nazi-looted 1

Bauer et al. v. B. and R. Toll , Tribunal de Grande Instance de Paris, judgment of 7 Nov. 2017 (No.

RG 17/58735, no. 1/FF).

A. Quinn, French Court Orders Return of Pissarro Looted by Vichy Government, New York Times , 8 Nov. 2017, . It is reported that the decision is being appealed.

Idem . Words of parties representatives (Ron Soffer for defendants, Cedric Fischer for claimants) as cited in the New York Times article.

Rathaus Landeshauptstadt Mnchen, Umschau 140 / 2017: Vergleich zur Beilegung der Auseinandersetzung im Falle des Gemldes Sumpflegende von Paul Klee, 26 July 2017 (Press Release Municipality of Munchen, see ); See also

nytimes.com/2017/07/26/arts/design/after-26-years-munich-settles-case-over-a-klee-looted-by-nazis.html> and .

*

Grotius Centre for International Legal Studies, Leiden University. General secretary Dutch Restitutions Committee (2002-2016). The author would like to thank Sergey Vasiliev, Prof.

Nico Schrijver, Patricia Kennedy Grimsted and Weyer VerLoren van Themaat for their valuable comments. Also, the author is indebted to Roos Hoek for her research assistance. This article is dedicated to the memory of the late Professor Norman Palmer, Q.C., C.B.E.

art.5 And, lastly, as another remarkable recent case example: in February 2017 the Dutch Restitutions Committee recommended the return to a Polish family of a family portrait by J.F.A. Tischbein that had been looted during the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939.6

The increasing number and changing nature of such cases raise the question as to whether clear international standards exist with regard to private claims to Nazi-looted art.7

At the interstate level such rules exist: cultural objects have a protected status and the obligation to return cultural objects taken during armed conflict to the State from which they came is well-accepted under international law.8 This article will not deal with rights of States but will focus on the position of private (non-Sate) parties.9 In 1998, these rights were addressed in the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-confiscated Art . This non-binding declaration, signed by 44 governments, introduced the international standard that former owners or their heirs are entitled to a just and fair solution with regard to Nazi-confiscated art that had not been restituted to them earlier.10 Whereas in 1998 the focus was primarily on claims by family members of Jewish Holocaust victims whose unclaimed confiscated artefacts were in western museum collections, today the array of claims has grown much wider. Claimants are now no longer necessarily relatives of Holocaust victims, and a confiscated work of art may surface in any public or private collection in the world.

Nor are claims limited to art confiscated by the Nazis but may concern cultural objects taken by others than the Nazis, or art that was sold by refugees in a neutral country such as Switzerland: so-called Fluchtgut (escape-goods). These developments are an indication that the just and fair rule, developed to address the rights of private dispossessed owners, is evolving. The question is, in what direction and by what logic?

International practice today is typified by a lack of transparency: often cases are settled works are cleared in a confidential agreement without legal argumentation, as in the Munich case. However understandable in specific cases, this hinders the development of a consistent, predictable and understandable set of norms, while openness would seem important given conflicting outcomes to similar cases.11 It is desirable for similar cases to be treated similarly (and different cases differently), but in order for this to be so, one must agree on which relevant facts need to be similar. The soft-law norm (prescribing just and fair solutions) is open and still unclear, which means that there is a need for precedents

Lewenstein et al v. Bayerische Landesbank , No. 17-cv-0160, U.S. NYSD, Complaint 3 March 2017. See also hereafter, 2.3.1.

Recommendation of the Advisory Committee on the Assessment of Restitution Applications for Items of Cultural Value and the Second World War (in short: Dutch Restitutions Committee) regarding Krasicki (RC 1.152) of 20 Feb. 2017; N.B. in 2005, the UK Spoliation Advisory Panel also upheld a claim regarding a non-Nazi taking in its Report in respect of a 12th-century manuscript now in the possession of the British Library of 23 March 2005.

The term Nazi-looted art can be used for various types of losses of cultural objects during the Second World War. This article will focus on losses by persecuted owners in Western Europe. See below, section 1.

Interstate restitution as reparations for violations of the laws of war. On the development of this norm, see, for example, Ana Vrdoljak Enforcement of Restitution of Cultural Heritage through Peace Agreements in Francesco Francioni and James Gordley (eds), Enforcing International Cultural Heritage Law (OUP, 2013), 23. See below, section 1.2.1.

Id . Obviously, the two normative frameworks are intertwined. Below, section 1.

Washington Conference Principles on Nazi Confiscated Art (Washington Principles) in J.D.

Bindenagel (ed), Washington Conference on Holocaust-Era Assets (State Department, 1999) 971-97. Principle VIII. Citation hereunder in section 1.1 and see:

hlcst/270431.htm>.

See below, section 1.3.

case law to further develop that norm. The positive legal framework, on the other hand, is highly fragmented, and courts of law are often not able to assess claims on their merits.

The expiration of post-war restitution laws, the non-retroactivity of conventional norms, and various legal concepts such as limitation periods for claims or adverse possession, are reasons for this.12 And although several Western European countries have established special committees to advise on these claims, their mandate is limited.13 That leaves a second important question open: who is to monitor compliance and explain the norm that individual owners have a right to a just and fair solution regarding artefacts lost in the course of the Second World War, as propagated by the international community since 1998?