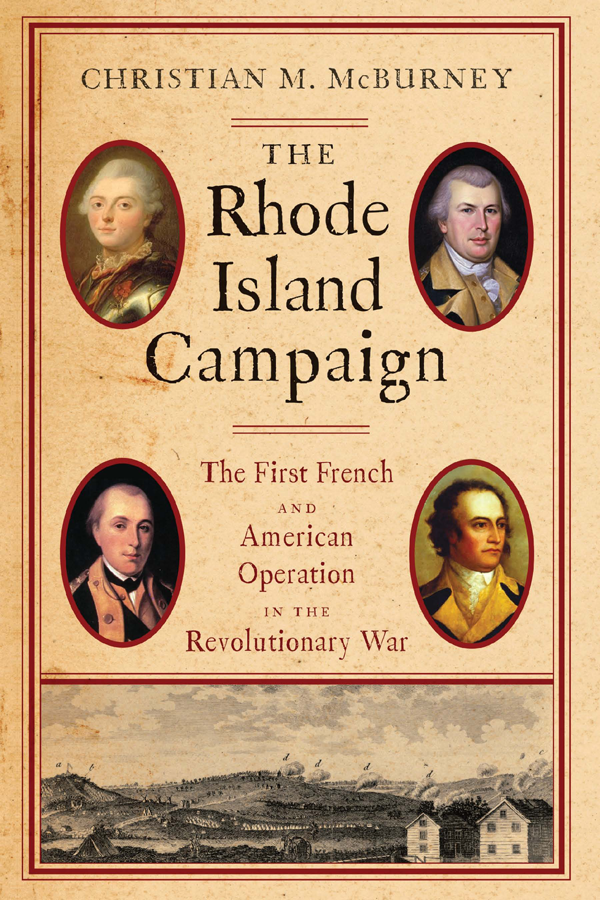

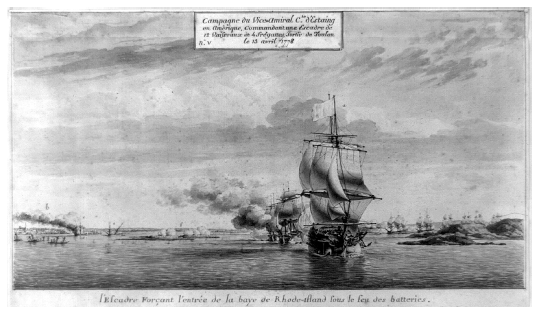

Frontispiece: The French squadron under the command of Vice Admiral Charles Henri Thodat, Comte dEstaing, exchanging fire with British shore batteries in Rhode Island. (Library of Congress)

Copyright 2011 Christian M. McBurney

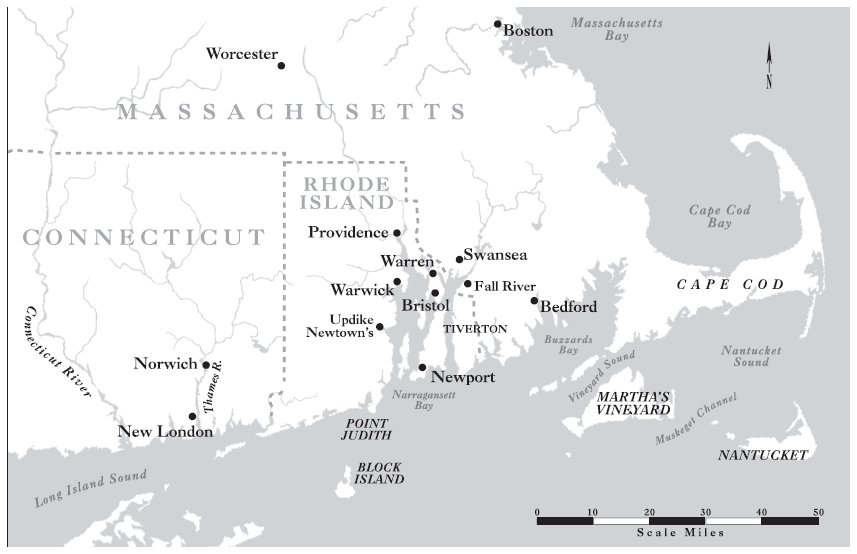

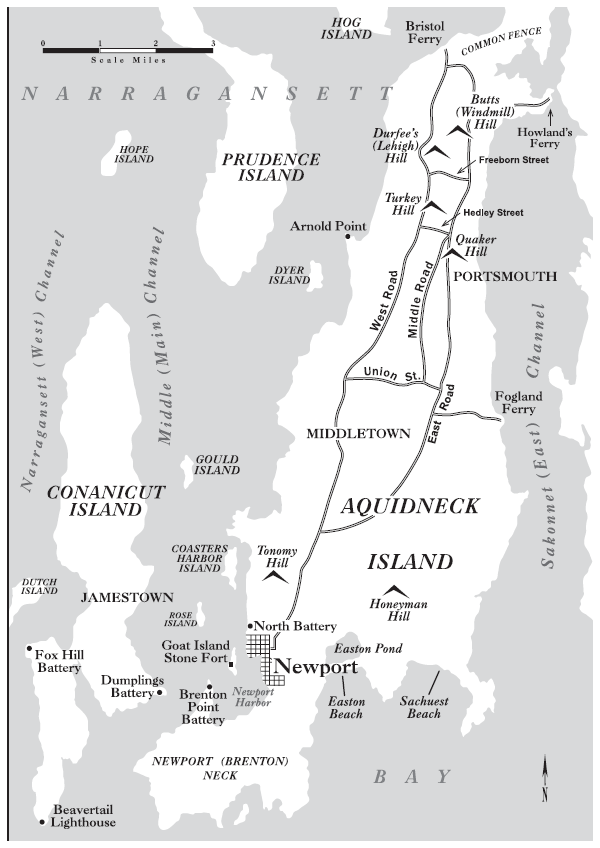

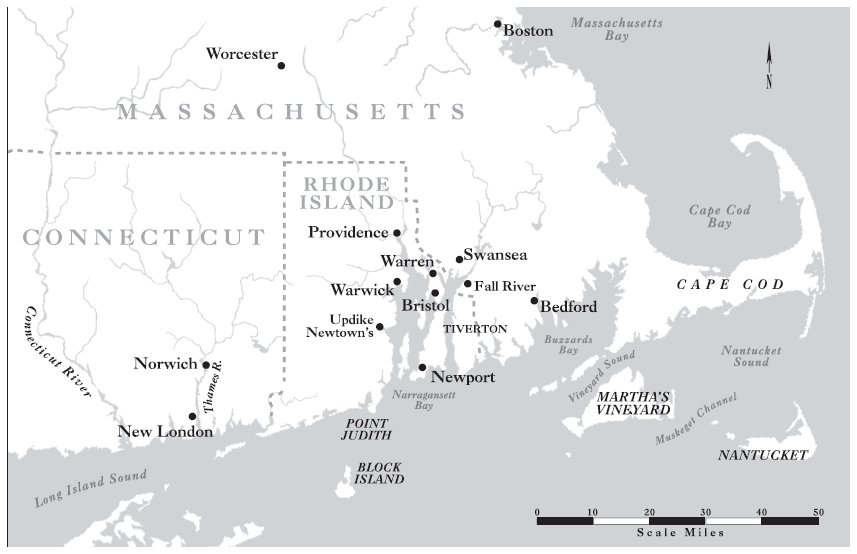

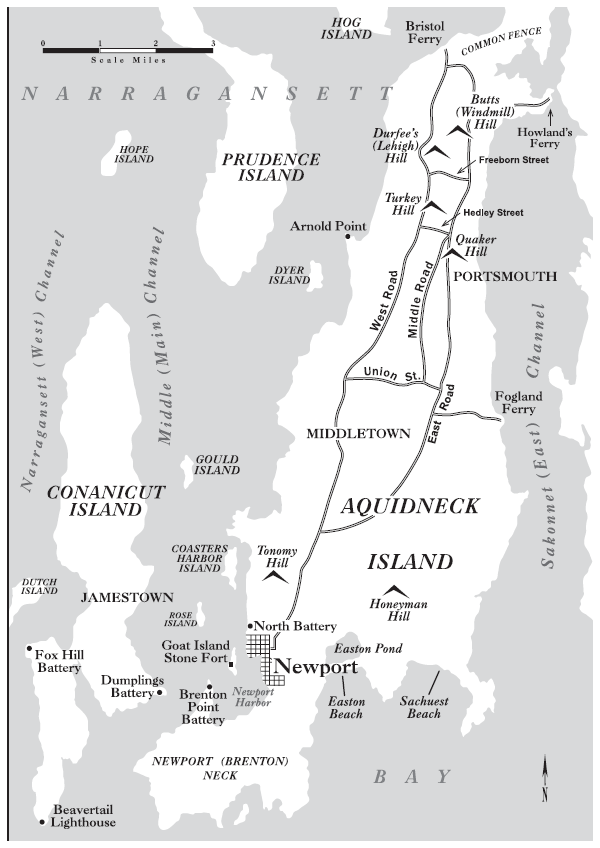

Reference Maps copyright 2011 Westholme Publishing

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Also available in paperback.

Produced in the United States of America.

Preface

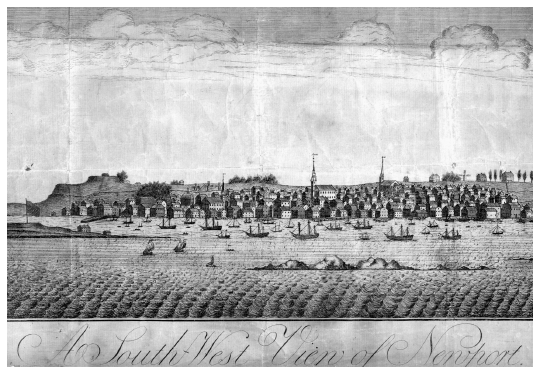

IGNORING THE CRASH OF CANNON AND MUSKETRY, the elegantly uniformed captain of a 74-gun French warship calmly orders his crew to open fire on a 50-gun British vessel.... A terrified British private presses against a dirt earthwork during an overnight artillery barrage as American shells explode around him.... A young Massachusetts militiaman, who only a month earlier was preparing to harvest crops on his fathers farm, crouches behind a stone wall, waiting to ambush a column of red-coated troops.... A former slave, now a private in a Rhode Island regiment of Continental soldiers, prepares to repel a third charge by professional Hessian troops. These are scenes from the Rhode Island campaignthe memorable effort by newly allied French and American forces to recapture British-occupied Newport, Rhode Island, in July and August of 1778.

The Rhode Island campaign did not involve the main British and Continental armies, nor did it directly affect the course of the war; it featured only one major engagementthe inconclusive Battle of Rhode Island. Still, to overlook its unique significance would be a mistake.

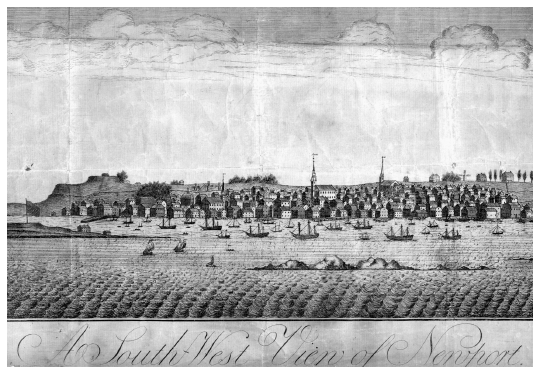

The Rhode Island campaign is most significant because it featured the first major joint operation undertaken by French and American forces against the British. The appearance of Vice Admiral Charles Henri Thodat, Comte dEstaings powerful French squadron off the North American coast in early July 1778 was an ill omen for the British. With the balance of naval power shifted, the allies hoped the war could be quickly won. When it was not, campaign disappointments spiraled into acrimonious name-calling between American andFrench officersforcing major figures to step forward and smooth a relationship each needed to defeat their common foe.

The military significance of the Battle of Rhode Island has also been underestimated. Aside from the battles at Bunker Hill, Lexington and Concord, and Bennington, Vermont, it caused more casualties than any New England engagement of the war. And while the August 29, 1778, clash ended allied attempts to recapture Newport, it revealed numerous positive signs. Continental troops on the American armys left wing had fought with vigor against seasoned British regular troops. And on its right (which featured the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, an outfit filled with freed slaves and other persons of color) Continentals repelled three charges by Hessian regulars, forcing them to flee the fielda rare accomplishment. Along with the June 1778 Battle of Monmouth (often inaccurately referred to as the last major battle in the north), the Battle of Rhode Island proved that solid instruction and battlefield experience were shaping the Continental army into an effective fighting force. The battle also highlighted the improving accuracy of American artillery, and even the fighting potential of New England militia units.

Nor have British naval losses in the Rhode Island campaign been sufficiently appreciated. When the French squadron forced its way into Narragansett Bay, the British burned or sank five of their own 32- and 28-gun frigates, two 14-gun sloops, and three armed galleys in order to prevent their capture. This loss of warships was the British navys most substantial of any campaign in the entire war.

Many of the top officers in the Revolutionary War played prominent roles in the Rhode Island campaign. The allied side boasted Nathanael Greene, Marquis de Lafayette, Comte dEstaing, and John Sullivan. British participants included Viscount Richard Howe and Sir Henry Clinton. Letters quoted in this book include those to or from Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Abigail Adams, Alexander Hamilton, Paul Revere, and John Hancock. A total of eighty-five letters to or from George Washington are cited. Just as important, however, are the numerous citations to diaries and letters of common soldiers and civilians on both sides.

Finally, the Rhode Island campaign was one of the most complicated and multifaceted events of the war. Each squadron commanderAdmiral Viscount Richard Howe for the British and d Estaing for the Frenchhad to make a number of crucial decisions, including whetherto limit his attention to his immediate counterpart or attempt to cooperate with ground forces. The choices they made spark controversy to this day. In the midst of launching a potentially war-changing campaign, the American and French allies had to figure out how to cooperate effectively, despite different languages, political and social systems, and military traditions. To retake Newport, the allies counted on New England states to quickly raise, equip, and send sufficient troopsa traditionally serious challenge for these virtually independent governments. The campaign featured one of the few major American siege operations of the war (the others occurred at Boston, Savannah, Fort Ninety-Six in South Carolina, and Yorktown). Weather figured prominently in each sides fortunes. Hurricane winds forestalled one imminent sea battle; later, the winds sudden disappearance slowed a British naval relief force long enough to allow an American army to escape from Aquidneck Island.

Next to the Boston campaign of 17751776, the Rhode Island theater of warthe area of southeastern New England most affected by the British occupation of Newport from December 1776 through October 1779and its associated campaign were the most important in New England. For nearly three years, New Englanders lived in constant fear that the British would use Newport as a base from which to attack Providence and then Boston. As a result, Rhode Island became and remained an armed camp. The British occupation of Newport spurred four major American troop call-ups. Each time, thousands of Massachusetts militia and state troops from Boston and surrounding counties, Worcester and surrounding counties, and from Bristol, Barnstable, and Plymouth Counties in southeastern Massachusetts answered the call, as did hundreds from southeastern Connecticut and thousands more from Rhode Island. Even New Hampshire sent about two thousand troops.

This book tells the story of the Rhode Island campaign, with all of its drama, twists, successes, and failures. It is hoped that after finishing it, readers will more fully appreciate the campaigns important role in the Revolutionary War.