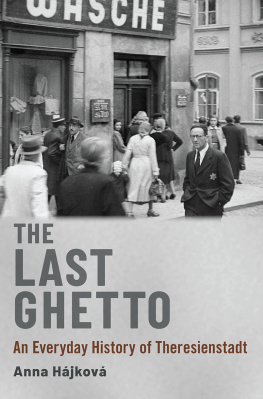

The Last Ghetto

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hajkova, Anna, author.

Title: The last ghetto : an everyday history of Theresienstadt / Anna Hajkova.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2020] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020012854 (print) | LCCN 2020012855 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780190051778 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190051792 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Theresienstadt (Concentration camp)History. |

Concentration campsCzech RepublicTerezin (Ustecky kraj)

Classification: LCC D805.5.T54 H35 2020 (print) |

LCC D805.5.T54 (ebook) | DDC 940.53/1853716dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020012854

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020012855

For those who did not come back

Contents

In his diary, written while he was an inmate in Terezn, a prematurely aged young man named Gonda Redlich recorded a series of bizarre moments. Here is one:

A small child shouts at an old man, Stinky Jew! A man walks up to them and says, What are you doing? You should be ashamed of yourself! You are a Czech and you talk in such a vulgar way. This occurred in the ghetto in the year 1944. The child, the old man, and the manall of them were Jews. It happened in the city of Terezn, which was only recently named: ghetto Terezn.

This scene was one of many in which Redlich criticized the numerous Czech Jews who distanced themselves from their Jewish roots. Two months after he wrote the entry, Redlich was sent to Auschwitz, where he was killed, together with his wife and their baby.

Terezn offers many similar stories. These seemingly bizarre situations were part of the logic of the forced community. The Nazis fashioned Theresienstadt for their purposes but left the day-to-day administration of the ghetto to Jewish functionaries. Redlichs diary recounts numerous conflicts and controversies among the inmates; the SS (Schutzstaffel) were mostly absent. Other diarists likewise focused much more on their fellow inmates and material conditions than on their persecutors. The people in Terezn created and inhabited different groups and hierarchies. All four participants in this scenethe child, old man, passerby, and diaristexpressed and lived their place in the social structure in the ghetto society.Czech Jews controlled access to status and prestige. Redlich, the diarist, was no mere observer. As head of the Department of Youth Care, he bore some responsibility for the childs behavior; the Zionist Youth Care strove to raise children in the ghetto as conscious Jews. Meanwhile, the shadow of transportsto the Easthung over them all. Even the fate of the vignette is telling. Whether because it implied pedagogical failure or because it showed the dearth of solidarity among inmates, this entry was not included in the published Hebrew or English editions of Redlichs diary.

Terezn was a victim society in the Holocaust; it is necessary to go to the eye of the horrors, to observe with an empathetic eye, and then ask what it means. This book examines the world in which the inmates of Terezn lived: the beliefs, mentality, and dynamics of the forced community. Terezn was a ghetto, established by German authorities to constrict the people they confined there. Although deprivation and suffering shaped the society that emerged, these factors did not entirely define it. Prisoners communicated, formed groups, and created rules. A close examination of the society in Theresienstadt helps us understand how people adapted to and worked in an extreme society.

Studying the prisoners social relations shows that Nazi victims should be understood beyond the dynamic of the perpetrator-victim binary and should not be read through victims deaths alone. For a long time Holocaust studies focused on the perpetrators. Works that examine the victims, especially those that look at society in camps and ghettos, have often been judgmental or descriptive, as scholars struggled with how to address and account for the conflicts and inequalities among Holocaust victims. However, victims should not be defined by their imminent murder, nor should they be ennobled by their impending fate. We need to tell the history of the society of victims, while occasionally integrating, wherever pertinent, the perpetrators role. This focus allows us to highlight the issues of responsibility, agency, and powerlessness, as well as the human tendency to understand through judgment.

Among the ghettos Terezn was distinctive, notably because it was the transit point for all Czech Jews; a designated ghetto for the elderly; international with respect to its population; and long-lasting, surpassing even Lodz. Nevertheless, Terezn was part of an interlocking system and merits integration in the wider history of Nazi ghettos and places of detention. With that idea in mind, The Last Ghetto, though not explicitly comparative, offers a road map for how to think about and analyze prisoner societies in the Holocaust. Every camp and ghetto had a different social field: the prisoner population, the particulars of the perpetrators persecution, the distribution of resources, and chronology. Rather than focusing on what made each camp and ghetto unique, we should approach the study of prisoner society with a theoretically informed, unified, analytical framework. Moreover, studying society in Theresienstadt provides insights not only into prisoner society specifically, but more important, into human society at large. Even if many of the events of the Holocaust would not happen in the outside world, whether because of their violence or scale, society during the Holocaust is one of the many versions of what human society can be.

One goal in this history is to place Holocaust and Jewish history into the wider context of modern history. Another is to argue for combining empirical Holocaust research with relevant theories. Perhaps because this European genocide in the midst of the twentieth century was so horrible, historians often tend to view it outside of the European context. As a result, much is lost. The Holocaust was connected to the context and society it came from and thus needs to be viewed in this perspective. Similarly, the way that middle-class Jews from Central and Western Europe viewed and acclimated themselves to the ghetto contributes to our understanding of their social, cultural, and gender histories. For an entire civilization of Central European Jews, Theresienstadt was a final station on the way to murder. These peoples lives were artifacts of a previous European world, whose last traces we can find in Terezn; it was not another planet but a site where Central European cultures continued, albeit under duress. The same rules that underpinned society in the ghetto structured the societies outside it. Examining people in the ghetto tells us more about the Central and Western European middle class, both before and after the war.