Contents

Guide

Page List

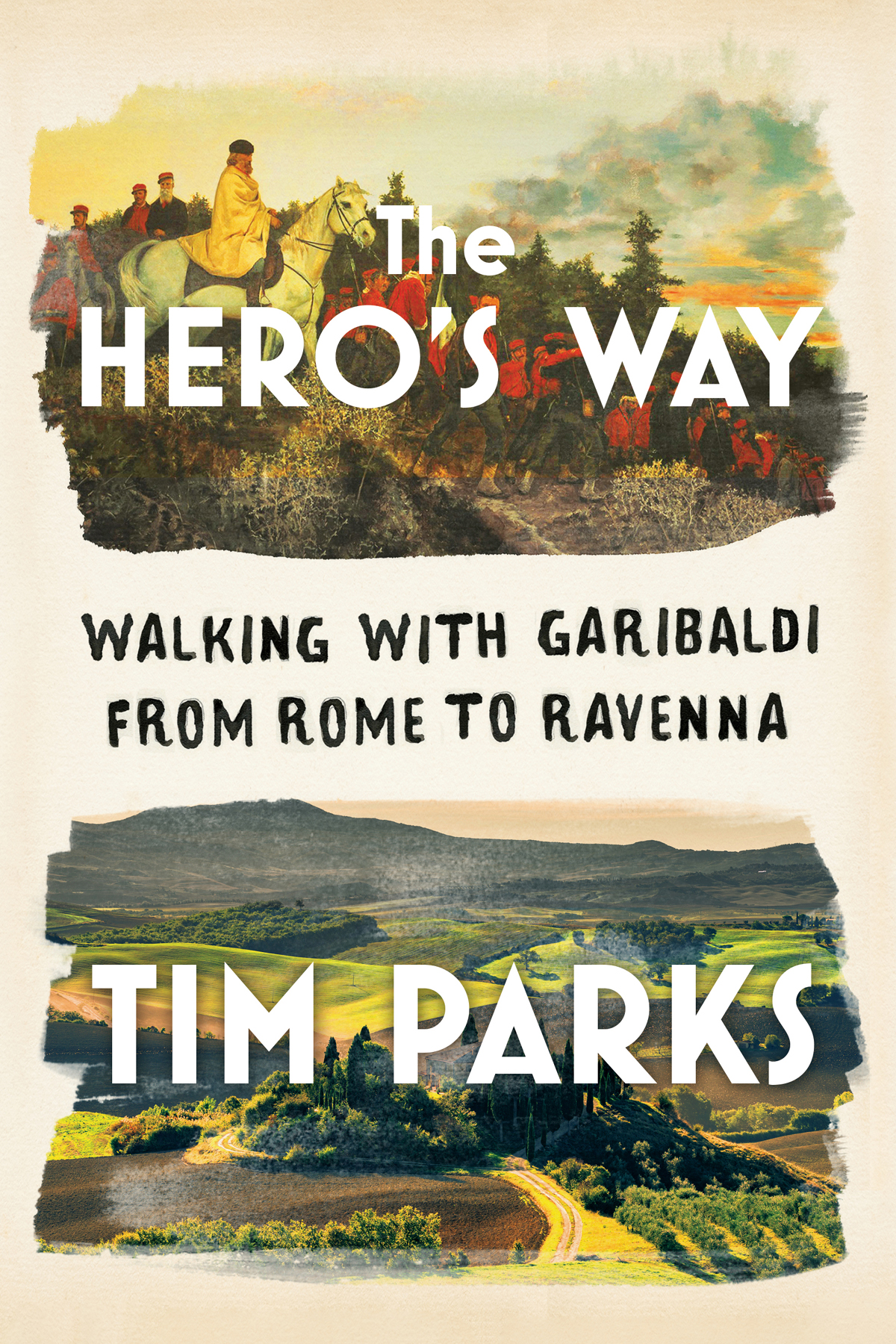

Tim Parks

The Heros Way

Walking with Garibaldi from Rome to Ravenna

For Eleonora, garibaldina

CONTENTS

One version of my life story might be that I met an Italian woman in 1978, married, moved to Italy and have lived here ever since. Without really choosing the place or it choosing me. But a happy curiosity of my Italian destiny was the way it was foreshadowed in adolescence. Faced with the need to choose a special subject for my history A level, I chose the Risorgimento, the process by which the various Italian statelets freed themselves from foreign domination and became, in 1861, a single unified nation. Under the guidance of a passionate teacher, we read a book of original documents from the time and learned of the four great artificers of modern Italy: the revolutionary republican Giuseppe Mazzini, who spent his entire life fomenting armed insurrections that invariably failed; the Machiavellian prime minister of Piedmont Camillo Cavour, who ably exploited rivalries between France and Austria to further Piedmontese expansionism, making his state the core of the emerging nation; the blundering but strangely effective Vittorio Emanuele II, King of Piedmont, who played a double game between his prime minister on the one side and the revolutionary patriots on the other; and finally Giuseppe Garibaldi, the extraordinary guerrilla warrior with a South American past who in 1860 astonished the world by taking a thousand rebels to the west coast of Sicily, capturing the island from a 20,000-strong Bourbon army, crossing to Calabria and driving north through Naples, gathering volunteers as he went, Rome bound, until he met the Piedmontese army racing south to stop him and handed all territorial gains to Vittorio Emanuele, creating the unified Italian state by fait accompli.

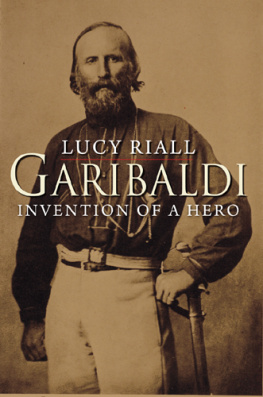

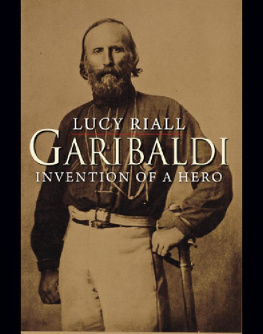

A year after those studies, in 1974, I took advantage of the newly introduced Interrail Pass to visit Italy for the first time and discovered in the process that I already knew a good percentage of the countrys street names. Viale Cavour, Via Mazzini, Corso Vittorio Emanuele, Piazza Garibaldi the four patriots are everywhere, their exploits celebrated in countless monuments, statues and plaques. By far the most attractive, both on the page and in stone, is Garibaldi: the deep-set eyes and bearded severity, the manly bearing beneath soldiers cap and gauchos poncho, still transmit a powerful charisma; the words roma o morte! inscribed beside the many balconies around the country where he pronounced his famous rallying cry still thrill the heart. Shame that the history books have him down as an ingenuous fellow, a tool in the hands of others, a lucky simpleton.

I began to doubt this description a decade later when asked to review biographies of the hero. Manipulated he may often have been, but simpleton he was not. He was canny, highly organized, creative. And if there was luck, which he acknowledged, it was luck he worked for. The injustice is interesting. Passionately local, ever divided into clans, factions, lobbies and corporations, Italians are not a people inclined to unity. Suspicion, conspiracy theories, cynicism abound. Infighting is the norm, defeatism is rife. Garibaldi, most unusually, set these negative qualities aside, and with them his republican ideals, to focus on a single goal: unity at any cost. He believed it could be achieved in his lifetime and, exhorting others to forget their differences and fight, even die, together, he achieved it. He thus becomes a challenge, even an accusation, for all those who like to feel that courage is futile and progress impossible. To make matters worse, he lived to tell the tale. Despite collecting a dozen bullet wounds over forty years of fighting, the hero died in his bed in 1882 at the age of seventy-four.

All the same I did not fall in love with Garibaldi till I came across A Diary of Events in Rome in 1849 by Gustav Hoffstetter. Hoffstetter was a Bavarian officer who volunteered to fight for the short-lived Roman Republic which replaced papal rule in February 1849 and fell to French troops after a two-month siege in early July. Garibaldi was one of the commanders in that battle, a battle he knew he could not win. However, it was not so much the doomed siege that moved me as the description of the heros extraordinary retreat from Rome through central Italy together with his Brazilian wife, Anita, and 4000 volunteers. He had sworn never to surrender to foreign soldiers on Italian soil. Arguably, it was what the hero learned and the example he set on that calamitous 400-mile march that would make his future triumph possible. Hoffstetter was his aide-de-camp. Rarely, reading his account, have I wished so much to live in a different time and another mans shoes. Or boots.

In 2019, 170 years after those events in Rome, I bought a pair of trekking shoes, persuaded my partner Eleonora to do the same and set off, in July, to retrace their steps.

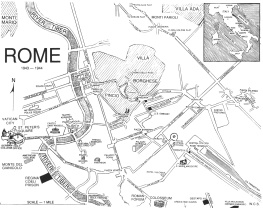

Aside from this principal map, it would be wonderful to pack this book with sketches and routes and plans. Its a tale of movement through a magnificent and varied landscape. A story of flight and pursuit. Cat and mouse. Or rather cats and mice. There are times when you need a sense of where everyone is in relation to this or that geographical feature, the mountains, the rivers, the sea. But maps are expensive and one would need so many. And these days most of us have the most wonderful and versatile maps right in our pockets. So, whenever you feel a little lost, as we often felt very lost along this trip, I suggest you pull out your phone. Each chapter, each day, opens with the names of the two, three or four towns or villages we passed through. Tap the names into Google Maps. Use the satellite view, the terrain view, the street view. I will do my best with the words, but they may be more alive and exciting if you know where we are.

DAY 1

2 July 1849 25 July 2019

Rome, Tivoli 22 miles

He had forty-eight hours to prepare for the journey. Weve been thinking about it for a year and more. Four thousand infantry had to be organized. Eight hundred cavalry. Mules, carts, munitions, food, medical services. A cannon. He was disappointed, having hoped for 10,000. We always knew it would be just us two, with our backpacks.

Still, we are leaving from the same place. Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano, Rome. The white facade of the basilica looms in the dark, its huge stone apostles silhouetted against the sky. He set out at sunset and had his men march through the night. No smoking was allowed. Orders were whispered down the lines. The enemy must not get wind. Our main enemies, we reckon, at least on this first stretch of the journey, will be traffic and heat. The forecast is for thirty-seven degrees, so the cool of the night is tempting. But to walk along fast roads in the dark would be suicidal. So we leave at 4.30 a.m., hoping to cover the twenty-mile hike before the sun is high.

The square is dead at this hour; San Giovanni isnt lit up. Our selfie on the steps shows only shadowy masonry behind wired-up smiles. No one has come to see us off. Garibaldi and his men were cheered on their way by a big crowd. The American journalist Margaret Fuller was there. Never have I seen a sight so beautiful, she reported, so romantic and sad... I saw the wounded... laden upon their baggage carts, I saw many youths, born to rich inheritance, carrying in a handkerchief all their worldly goods.

Next page