Contents

Guide

Terry Mort makes a fasinating read of every subject he takes up.

The Wall Street Journal

Terry Mort

Cheyenne Summer

The Battle of Beecher Island: A History

For Izabella, Brooks, Penelope and Zoe

INTRODUCTION

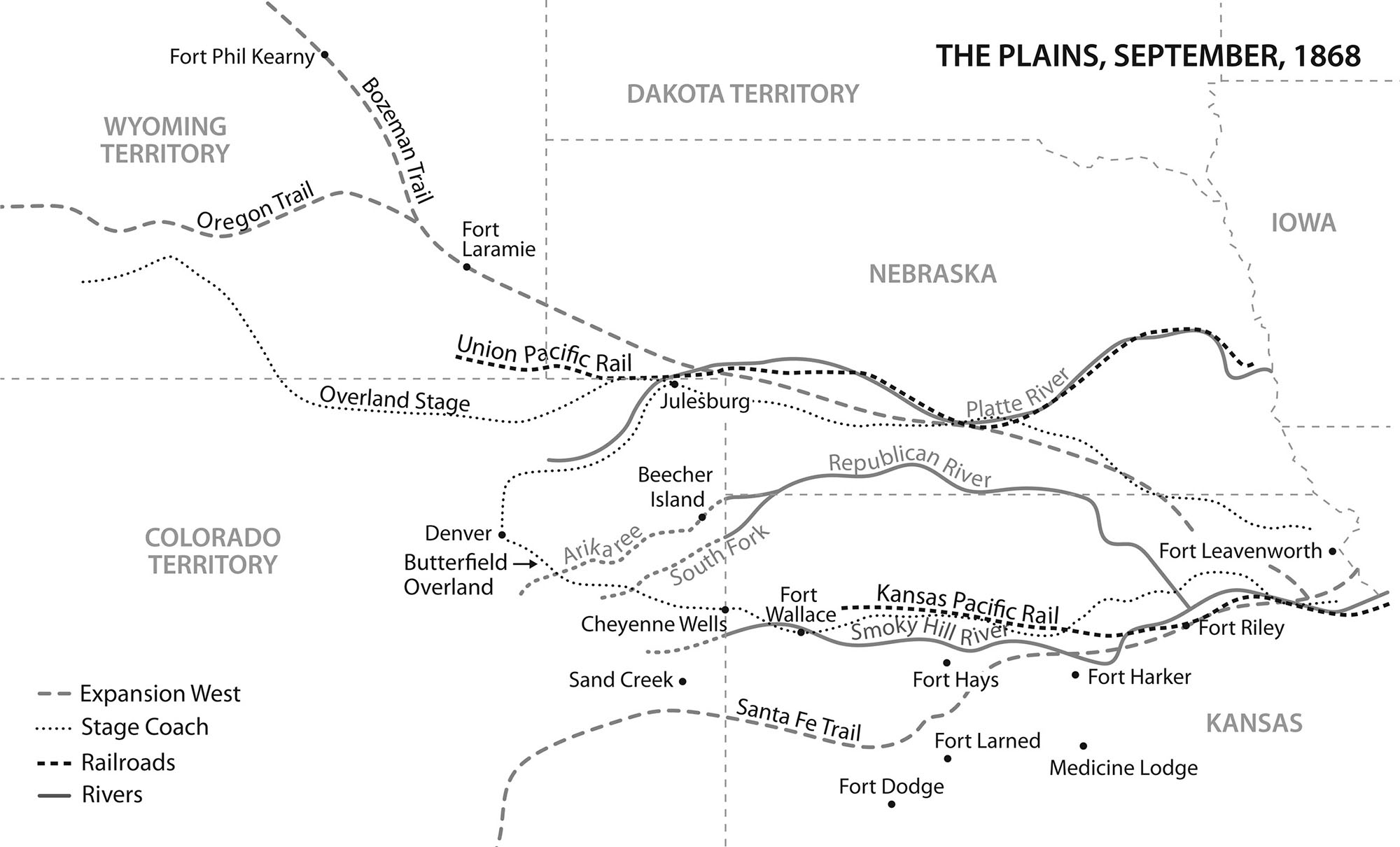

In the summer of 1868 General Phillip Sheridan was commander of the US Armys Department of the Missouri. He was responsible for the vast Plains that were the homelands of some of the most warlike and troublesome of the Native tribes. His territory comprised Missouri, Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico. And he had a problem. Those tribesnotably, the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapahowere raising havoc in the settlements, along the construction route of the Union Pacific Railroad and the emigrant wagon trail routes. Major George A. Forsyth, Sheridans inspector general of the department, wrote:

Upon the reoccupation of the southern and western frontier by government troops at the close of the [Civil War], the Indians, who had grown confident in their own strength, were greatly exasperated, and the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad across the continent to the Pacific coast, directly through their hunting grounds, drove them almost to frenzy. The spring of 1868 found them arrogant, defiant, and confident, and late in the summer of that year, they boldly threw off all concealment, abrogated their treaties, and entered upon the warpath. I have lying before me, as I write, tabulated statement of the outrages committed by the Indians within the Military Department of the Missouri from June until December of that year, and it shows one hundred and fifty-four murders of white settlers and freighters, and the capture of numerous women and children, the burning and sacking of farmhouses, ranches, and stage-coaches, and gives details of horror and outrage visited upon the women that are better imagined than described.

Sheridan didnt have enough troops or enough experienced officers to deal with the highly mobile Indian warriors who traveled the Great Plains as they wished, attacked where they chose, and disappeared into the seemingly endless prairie. Officers and men who knew anything about that business were very rare in the regular army. Jim Bridger, the old scout, summed up Sheridans dilemma when he said, Your boys who fought down South [i.e., in the Civil War] are crazy. They dont know anything about fighting Indians.

In fairness to the army, it could hardly have been otherwise. Most of the officers learned their trade in the Civil War. They fought in appalling battles that involved thousands of men marching shoulder to shoulder to attack enemy positions defended by thousands more, while both sides exchanged devastating artillery barrages that covered the field with the fog of gun smoke, confusion, noise, and sheer terror. Those tactics were absurdly inappropriate and useless against an elusive enemy like the Plains tribes. (Some thought the tactics were absurd, period.) Those few Indian leaders who heard about such battles were amazed that anyone could fight so foolishly and wastefully. The officers who survived and even prospered in the Civil War bloodletting might be competent soldiers in conventional, set-piece battles, but most of them didnt know what they were doing when it came to the warlike tribes. Whats more, newly minted graduates of West Pointthose who were sent to western outpostswere completely unprepared. The subject of Indian fighting was not, and had never been, a part of the Academys curriculum.

As one possible response to his problem, Sheridan decided to raise a company of frontier civilians who were experienced Indian fighters. Sheridan figured that a relatively small, well-armed group of frontier scouts might be worth many times that number of regularand often greenarmy troops. And although these civilian scouts would necessarily be under the command of regular army officers, a few wise old heads among the frontiersmen might balance their officers tactical naivet. Whats more, these men would not be used instead of the army patrols but in addition to the initiatives that were already underway, such as they were.

There was another reason why Sheridans idea seemed to make sense. The Indians were almost impossible to findunless they wanted to be found. And when they wanted to be found, it was because they had selected a time and place where they had a marked tactical advantage. An army patrol led by officers new to the business might wander fruitlessly for days across the Plains and never see an enemy. Then they would return with horses played out and nothing to show for the effort. Or they might never be heard from again, if they stumbled on a hidden and waiting enemy. But frontiersmen, who understood tracking and understood the ways of the tribes, might at the very least locate some significant pockets of hostiles. The officer commanding the scouts would then have the choice of attacking then and there, or, if the enemy force was too large, sending for the regulars.

So in Sheridans mind, it made a lot of sense to create an independent unit of experienced frontiersmen to scout against the tribesand to engage them, if the opportunity presented itself. And there were other good reasonsthe army could use the extra manpower. After years of the Civil War and the burgeoning national debt, Congress was not keen on spending for troops whose enlistment meant financial commitments of several years. The army was therefore stretched thin across the Western frontier, and the troops it did have were a mixed bag, at best. A team of temporary scouts therefore made some financial sense and was really the only alternative to budget-strapped departments like Sheridans. There was also a precedent for this kind of unit. The estimable scout Frank North and his brother Luther had organized and now commanded the Pawnee Battaliontwo hundred or so Pawnee warriors who were assigned to patrol and protect the Union Pacific Railroad as it moved slowly west. The Pawnee were the eternal and inveterate enemies of the Sioux and Cheyenne and were happy to take the white mans dollar to do what they had always done, anywayfight their tribal enemies.

So Sheridan decided to go ahead with the idea. He offered the job of recruiting and commanding the new unit of scouts to one of his favorite staff officers, George Sandy Forsyth, his inspector general. Forsyth jumped at the chance for a field command. He was a veteran of the Civil War and a competent soldier and had been breveted colonel for his conduct in the war. Like most professional officers of this time, he had no experience of Indian fighting. What little he knew about them was almost entirely secondhand. As he wrote in his memoirs:

My experience of military life having been gained solely in our civil war, the only fairly accurate knowledge I had of Indians had been picked up during a years service in the Department of the Missouri, as I travelled through its limits on duty as an inspector, and notwithstanding I had assimilated, or tried to, all that I had seen or heard regarding them, my knowledge was most meagre. It might have been summed up under three heads. First, that they were shrewd, crafty, treacherous, and brave. Secondly, that they were able warriors in that they took no unnecessary risks, attacked generally from ambush, and never in the open field unless in overwhelming numbers. Thirdly, that they were savages in all that the word implies, gave no quarter, and defeat at their hands meant annihilation, either in the field, or by torture at the stake.