Contents

Page List

Guide

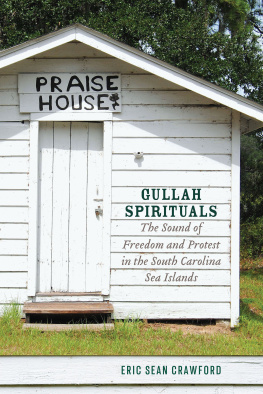

GULLAH SPIRITUALS

GULLAH SPIRITUALS

The Sound of Freedom and Protest in the South Carolina Sea Islands

ERIC SEAN CRAWFORD with BESSIE FOSTER CRAWFORD

2021 University of South Carolina

All Rights Reserved

Published by the University of South Carolina Press

Columbia, South Carolina 29208

www.uscpress.com

Manufactured in the United States of America

30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/.

ISBN: 978-1-64336-189-5 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978-1-64336-190-1 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-64336-191-8 (ebook)

The following material was reprinted with permission:

Thirty-Six South Carolina Spirituals by Carl Diton. Copyright 1928 (renewed) by G. Schirmer, Inc. International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved.

Reprinted by Permission.

Walk in Jerusalem, Just Like John

Im Going to Eat at the Welcome Table

May Be the List Time, I Dont Know

Ive Got a Home in the Rock, Dont You See

Ring the Bells

Guy Carawan, Sing for Freedom: The Story of the Civil Rights Movements Through Its Songs. Music examples reprinted by permission of New South Books, Inc.

Support for publication was provided by the AMS 75 PAYS Fund of the American Musicological Society, supported in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

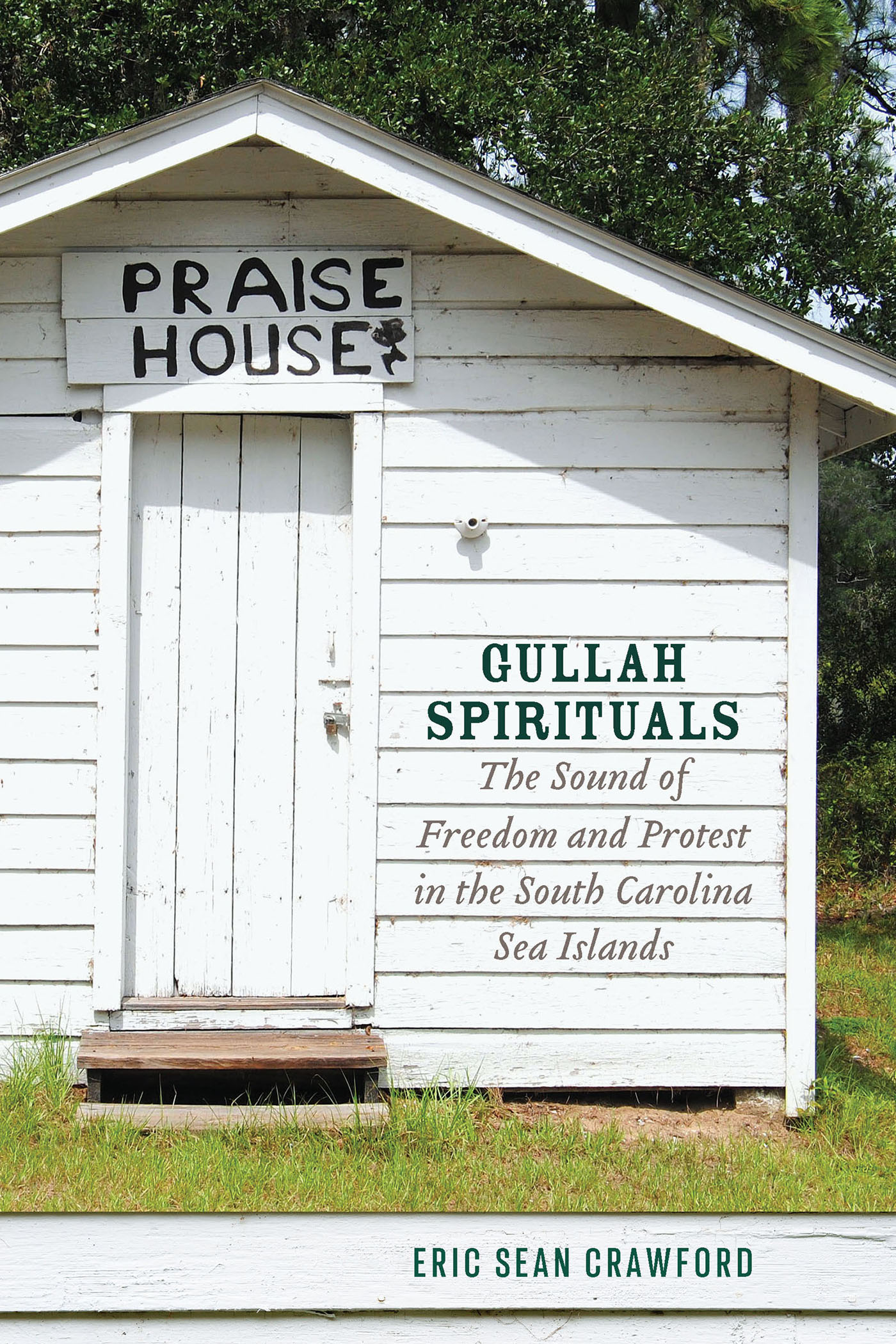

Front cover photograph: Eddings Point Community Praise House, Beaufort, SC, courtesy of Gwingle/Wikimedia Commons

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First, I give thanks to my Lord and Savior Jesus Christ for giving me patience in this long process. I must also recognize my mentors, Ernest James Brown, DMA, Carl Gordon Harris, DMA, and Marjorie Scott Johnson, PhD. They have made this journey possible, and I am eternally grateful.

I am indebted to my dear friend Alli Crandell, director of the Athenaeum Press at Coastal Carolina University, and the staffs at Penn Center, the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, and the Southern Folklife Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for granting me access to historical collections and permissions to use the reproductions in this document. I also thank ethnomusicologist Sandra Graham, who offered feedback and a tender shoulder in the early stages of this book.

I cannot fail to recognize my parents, Pastor Timothy and Dr. Bessie Crawford, who are the benchmarks for my life. They are truly the Wind Beneath My Wings. To my son Sean Timothy Crawford, I am a proud father, and I know you will accomplish great things. I am also thankful for the support of my brother, Dwayne Andre Crawford and his wife Kathy, Angie, and their children Andre, Taylor, and Kayla Marie.

Last, I recognize that this book would not have been possible without the help and inspiration of Deacon James Garfield Smalls, Minnie (Gracie) Gadson, and Deacon Joseph and Rosa Murray. Their commitment to keeping the Saint Helena Island song tradition alive makes them true ambassadors of the Gullah Geechee culture. I am truly fortunate to have them in my life.

Introduction

De ole sheep done kno de road

De ole sheep done kno de road

De ole sheep done kno de road

De young lam mus fin de way.

Saint Helena Negro spiritual

Each time I hear this popular refrain from Saint Helena Island, South Carolina, I think of those elderly singers on the island who continue a Gullah song tradition with unbroken ties to Americas slavery past. Indeed, they still remember traveling to church services by mule and watching their mothers and grandmothers singing and moving in the emotionally charged ring shout. Some can even recall singing more dignified spirituals during chapel services at Penn Normal, Industrial, and Agricultural School, one of the earliest educational institutions for newly freed slaves in the South. Yet readers will discover that these spirituals traveled well beyond Saint Helena Islands shores. Remarkably, these songs persevered despite the immense emotional and physical atrocities of the transatlantic slave trade and southern plantation life to influence many of the major events in American history.

My initial interest in Saint Helena Islands spirituals stemmed from a thesis entitled Music Education Through Gullah: The Legacy of a Forgotten Genre by former student Marianne Rice. She grew up near Saint Helena Island, and her mother Marlena Smalls is a well-known singer, actress, and educator. Marianne wrote about Gullahs ties to West Africa and the many well-known Gullah spirituals from the island, revealing a culture whose contributions to American history had been largely unacknowledged. Her writing caused me to reflect upon my undergraduate years at a Historically Black College and University (HBCU), where there was surprisingly little if any mention of Gullah culture in my classes, including the universitys choir, where spirituals were a staple of our musical repertoire. This awakening moment was the driving force in my decision to visit Saint Helena Island in the summer of 2009.

When I arrived on Saint Helena Island in Beaufort County, South Carolina, I was struck by its scenic marshlands, unspoiled beaches, and tree-lined roads defined by the hanging Spanish moss. Undoubtedly, such elements contributed to a much slower pace of life, and residents drove their cars below the speed limit so they could wave to the many walkers on the side of the road. It is obvious that they still remembered when walking was the norm and not the exception.

I attended a Sunday morning worship service at Historic Brick Baptist Church on Saint Helena Island, where I anticipated hearing some of the old spirituals. Before the Civil War, plantation owners brought their enslaved laborers to Brick Baptist to Christianize them and remove their perceived heathenish practices. These enslaved Africans had to sit unseen in the upstairs balcony, but they still took an active role in the congregational singing, especially the Europeanized hymns that would later serve as free musical material for their Negro spirituals. To my dismay, I heard none of the Gullah spirituals during Brick Baptists worship service, only hymns and popular gospel songs. However, a kind church member informed me of an evening prays (praise) house service not far away where I might hear the old songs.

I vividly remember hearing Deacon James Garfield Smalls fervently raise several of his songs at the Jenkins Praise House, one of two prays houses still holding Sunday evening services. His voice swept through this tiny wooden structure with a force that seemed to bring us all back to the bygone era of slavery when Negro spirituals were first forged. Indeed, such singing seemed to honor all those who had come before, and I felt an instant connection to my own childhood as a kid growing up in Millington, Tennessee, where I attended Saint James Christian Methodist Episcopal Church. After forty years, I can still recall the foot-tapping of my pastors wife to the cadence of her husbands sermons and the ever-present congregational responses of Amen and Preach Pastor. My own cultural past found a kinship and common ground within this prays house.