Contents

Guide

Page List

TABLE of CONTENTS

You were always bound to get something good to eat. I thought she was God, could make anything. I wanted to be just like her.

DENISE RANDALL-RAVANEL, MY OLDEST GRANDCHILD

WELCOME to EDISTO ISLAND

When you cross the Dawhoo Bridge that connects Edisto Island to the rest of South Carolina, youre in Heaven. Heaven on Earth, that is.

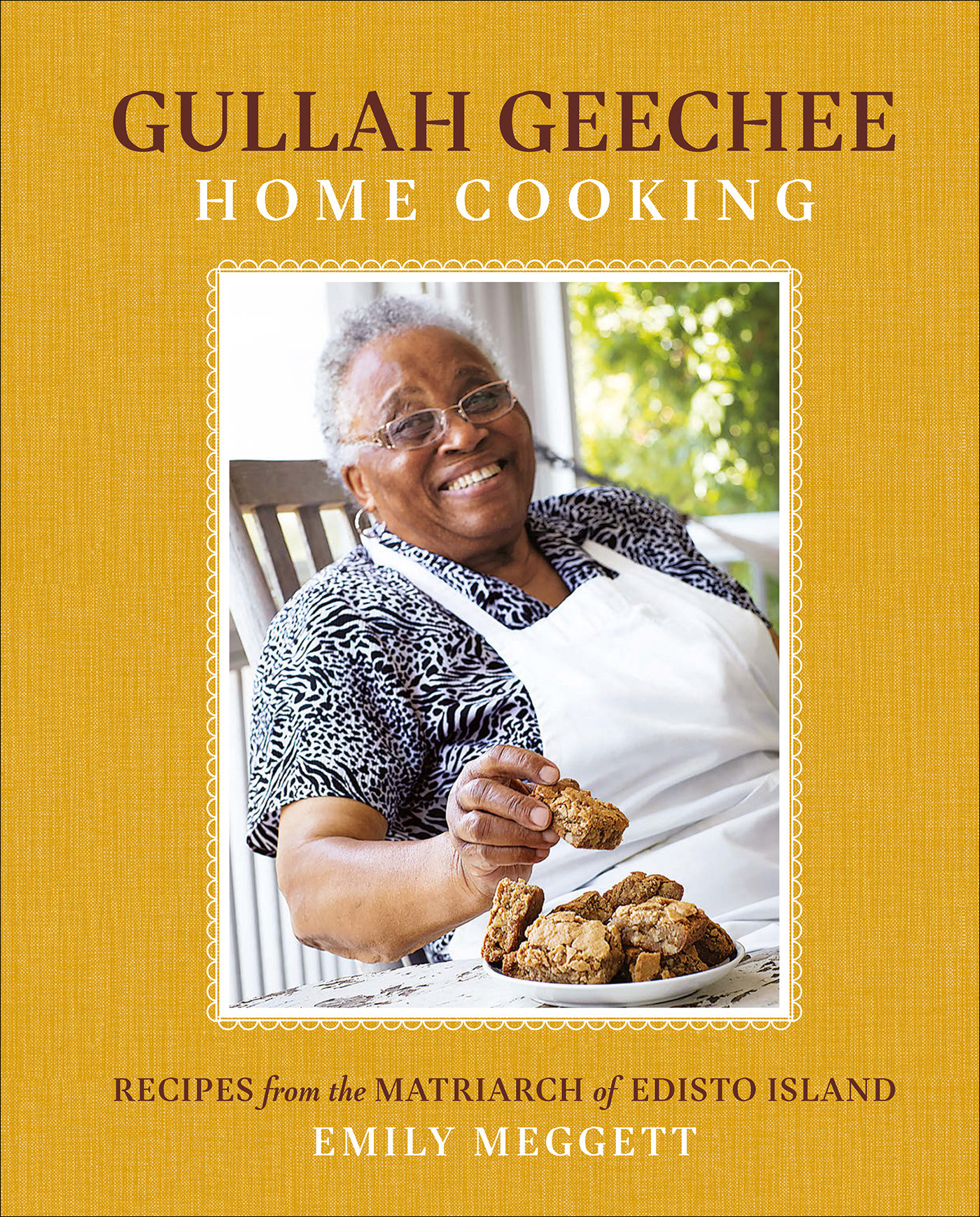

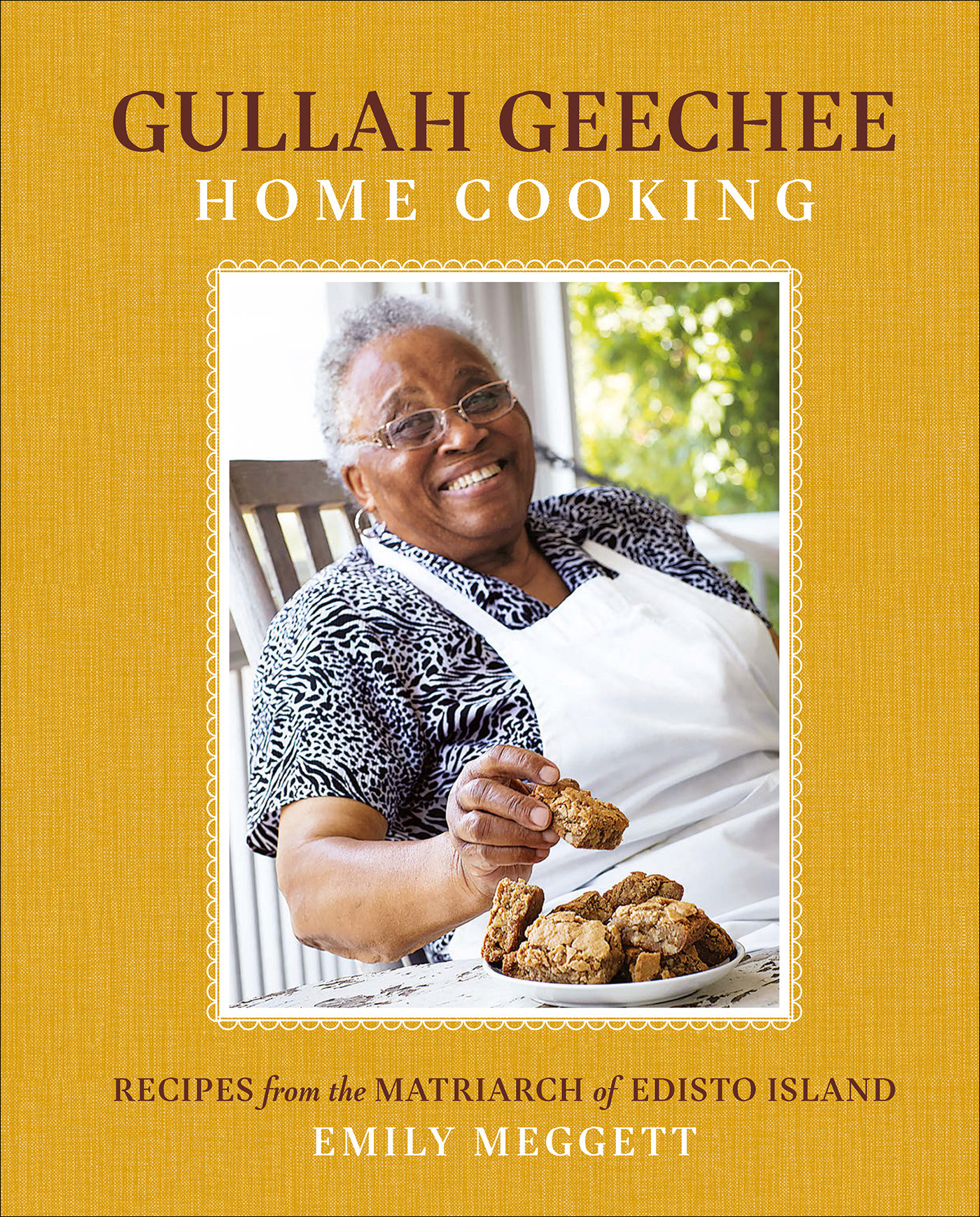

Im Emily Hutchinson Meggett. Most people know me as M.P. I was born on Edisto Island, South Carolina, on November 19, 1932.

Forty-two miles south of Charleston and home to just over 2,000 people, Edisto Island was a place where everyone knew everyone when I was growing up. There wasnt much out on the island then. The one way on, one way off Dawhoo Bridge was just a plank bridge. Highway 174 used to be just a dirt road. Some of the landmarks I remember on Highway 174 are the Eubank Store, Seaside Elementary, Edisto Post Office, Zion Church, Trinity Episcopal Church, New First Baptist Church, and Larimer High School.

Though small, this island is one of the most blessed places on Earth. Edisto has these great, big live oak trees that are full of Spanish moss, so many different types of animalsbirds and fish especiallyand a beach that has some of the biggest shells youve ever seen in your life. On this island, were insulated versus isolated (to quote Queen Quet, the Chieftess of the Gullah Geechee nation) from the hustle and bustle of city life. So Edisto maintains a sense of peace and stillness that my people have lived with for many generations.

A welcome sign to Edisto Island; crabs from South Carolina; an Edisto marsh; Indigo Hill, home of the matriarch; the Hutchinson House on Edisto Island

Many of my ancestors and elders would work in fields during the day, growing cotton, corn, potatoes, and other vegetables, then go home and tend to their own gardens. My grandparents owned ten acres of land. We didnt have no fertilizer for the garden. Mama would use manure from the chicken house, the horse stable, and the cow pen. We had corn (white and yellow), butter beans, lima beans, peas, black-eyed and field peas, okra, watermelon, cantaloupe, squash, onions, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, white potatoes, sugarcane, sugar millet, and our own rice pond. We had chicken, turkey, duck; we had fowl, hogs; we had horses.

We didnt have to go to the store for any fresh vegetables, either. We just went for items like sugar and flour. Thats because, like generations before us, we grew our own vegetables and there were plenty of fruit trees. We were so blessed. We even had our own livestock for meat, and my uncles would bring back plenty from fishing and hunting. Raccoon, squirrel, and quailwe ate all of that. I remember them hanging the coon from a tree and skinning it. When they got through skinning it, theyd salt it then leave it for a day or two to drysometimes outside in the tree, other times on ice. Let it dry out and then take it down and cut it up, soak it for an hour or two, and cook it. If its cooked the right way, you cant tell if its chicken or turkey. Now thats some good cooking, Ill tell ya.

When my grandmother and uncle and those would kill cows and pigs, they had a little smokehouse outside. Whatever they was gon smoke, they smoked it. Whatever they wasnt gon smoke, they preserved it in the ground. The guy would come around and bring the ice. Theyd dig a hole in the ground, put the ice in the ground in a brown bag along with whatever meat they got. Theyd wrap it up, lay it on that ice, put a piece of rooftop tin on that ice to keep the dirt out, and cover it up. And the ice would last for days. They didnt have no refrigerator. We didnt get a refrigerator until the early fifties.

Because we had our own rice pond, we harvested our own rice. Rice is a big deal to the Gullah Geechee people. Most of us have roots in Sierra Leone, a country known for its legacy of skilled rice farmers who could grow and cook rice. Just as it is with us, rice is served with most dishes there, too. We also harvested our own sugarcane, and when the corn was ready to be picked, whether it was yellow or white corn, wed have it ground into grits. My uncle Nem would break the corn and put it in the back of the horse and buggy. On Wednesday, wed shuck the corn. On Thursday and Friday, wed have to shell the corn off the cob and put it in these big ol bags. Then, on Saturday, a man would come from Jericho, which was about twenty miles out, and pick up the corn and take it to Jericho Mill. When they got through processing the corn, they would bring it back, and you would have a twenty-five- or fifty-pound bag of grits and another of husks. The same with the white one and the yellow one. Then youd have the cornmeal, the yellow and the white. Thats what you ate off of for the winter, so you didnt have to go to the store. The husks went to the hogs.

See, as most cities moved toward becoming more industrial, Edisto was still agricultural. We held on to the old ways of doing things for a very long time, some of it still to this day. Working the land is one of them. It was our way of surviving. Its how we fed ourselves, empowered ourselves, and kept our ancestral ties intact.

My family tree is deeply rooted in Edisto. In fact, my great-grandfather, Jim Hutchinson, was known as one of the Kings of Edisto Island. He was born in 1836 on Peters Point Plantation. According to our family history, his mother, Maria, was enslaved to his father, Isaac Jenkins Mikell, the plantation owner. He served the country during the Civil War, then got involved in local politics. A letter my great-grandfather wrote to the governor at the time, Robert Scott, resulted in a good bit of plantation land being divided among freed black people. One of his sons, Henry (my grandfathers brother), built a family home around 1885 that still stands today: the Hutchinson House.

Like many Black people in the thirties and forties, my mother, Laura Hutchinson, joined the Great Migration and moved north to earn more money. So my grandmother Elizabeth Major Hutchinson and my uncles, Isaiah and Luther Hutchinson, raised me. One of my uncles lived in the house with us. My other uncle lived in Charleston. When everybody saw his light-blue pickup truck bumping down the road, youd think Santa Claus was coming. Hed be passing out apples, oranges, candy, and shoes. Sometimes hed even bring furniture that folk from the city had thrown out.

When I say mama, Im referring to my grandmother. Mama, my uncle, his wife, me, my sister Bernice, and my cousins Marion, Edmond, Sonny, James, Emma, Jesse, and Gillie all lived under the same roof at the same time. We ate together, too. Whoever didnt fit at the kitchen table ate at the dining room table. We ate our meals as a family, though, and when I became a mother, I did my best to keep that tradition going.