The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Foreword

In 1969, I found myself twenty-three years old steering a boat across the May River in Bluffton, navigating a tricky route to a mysterious place called Daufuskie Island. It was the first year of teacher integration in the public school system in South Carolina, and I spent one of the richest and most pleasurable years of my life teaching eighteen black children from grades 5 through 8 in a two-room schoolhouse in the middle of a Carolina sea island that did not have a single paved road.

Until that time, segregation had been the law of the land in the South, and I was raised up in a tradition of a separate but equal school system. It took me a single morning with my new students to discover the equal part was a complete lie. My eighteen students all read below the first-grade level, five could not write their names or complete the ABCS, and none of them knew the name of the ocean that washed against the eastern shore of their pristine and paradisiacal island. They lived in one of the most beautiful and undiscovered places on earth, and all of those Daufuskie children had the run of the island.

That night I wrote the superintendent of schools a fiery, intemperate letter denouncing the school system for its cruel incompetence. The superintendent did not like my letter, did not like me, and twelve months later fired me for gross neglect of duty, conduct unbecoming a professional educator, being AWOL, and insubordination. Though he stole my teaching career from me, he could not touch that magnificent, life-changing year the children of Daufuskie had handed me like a gift.

I leapt into the kids lives and they caught me with their arms wide open. Theyd never heard of Halloween, and I took them to my home-town for Halloween. Theyd never heard of Washington, D.C., and I took them to spend five days in one of my favorite cities in the world. Though they had never heard of classical music, when the deputy school superintendent came out for his annual visit, I encouraged several of the kids to get into a heated discussion, arguing whether they preferred Beethoven, Tschaikovsky, or Rimsky-Korsakov. One of those kids was the impish and delightful Sallie Ann Robinson, the author of this splendid book.

When I heard that Sallie Ann, a child of Daufuskie, was publishing a book with the University of North Carolina Press, it ranked with the best days of my life. I know the full measure of struggle that she endured in her quest to lift herself out of a life of great hardship to be published by an arm of the university that gave Thomas Wolfe to the world. I know the names of many of the people and the teachers who came after me. I know about the California boys and girls from the University of California, Santa Cruz, and the great, charismatic Herman Blake, who provided a free education for some of the Daufuskie kids. That Sallie Ann Robinson is the author of a published book is a bright miracle that adds grandeur and hope to the American story we are all telling.

Here is the great glory of this book, thoughit will teach you how to eat much better than you did before you read it. My year on Daufuskie was one of the best-fed years of my overfed life. Daufuskie Islanders make the best deviled crab and deviled eggsthey are terrific with all dishes with the word devil in them. Sallie Ann could make biscuits that were light and feathery and teacher-pleasing when she was eleven years old. The island teems with deer and boar, rabbit and quail. The waters around it are tide-swollen, bringing the billion-footed incursion of shrimp into the rivers and marshes where Daufuskie nets await them for transportation to the kitchen tables of the island. I ate like a king in my one year on the island, and you will eat like me because Sallie Ann Robinson, one of the children I loved and taught, and wrote about in The Water Is Wide, grew up and got herself smart and ambitious and wonderfuland decided to write herself a book. I think I may be the proudest man on earth.

Pat Conroy

Acknowledgments

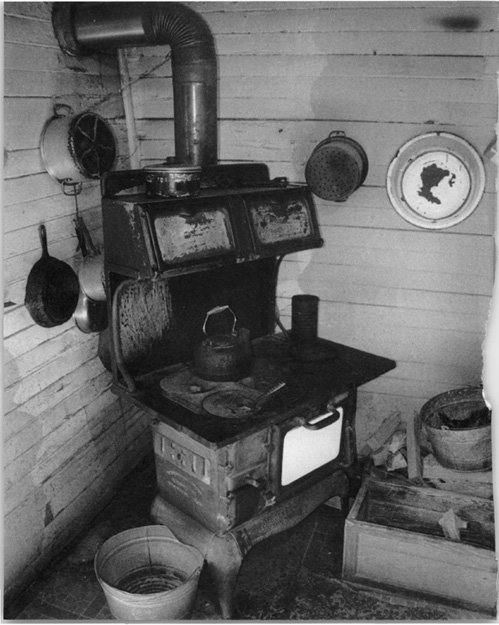

It all begins with Pop and Momma. As far back as I can remember, I have happy memories of the old days, now long gone but never forgotten. As a child growing up on Daufuskie, I had so much to be thankful for. We were always there for each other, no matter how tough times got. Momma and Pop used to tell us many stories about how hard things were for them when they were growing up, but how hard times never hurt them. Pop believed that a good, backbreaking day of work was good for you and made you stronger. A full belly, a good nights rest, and getting up with the chickens kept you going.

We never had as much as some but always had what was needed. Pop and Momma were known as two of a kind; they both worked hard and had big hearts, and they shared with everyone. When they started their life together, I was about four months old, as they united two already-made families, eight children (two boys and six girls), under one roof in a two-bedroom house. Two years later they added a set of twin girls of their own. Our sleeping space was tight. The boys slept on the couch or a pad on the floor, and we girls slept in a big bed pushed up against the wall.

Even though Pop and Momma had very little education, they knew what was important for our future: they taught us to do the right thing, and they encouraged us to get a good education. They made us study hard and do our homework before we did any yardwork or housework during the school term. Hard work, cleanliness, and manners will take you where money wont, they drilled into us and reminded us constantly.

Pop and Momma were always busy doing something. They didnt often stop to give us hugs or kisses or to say out loud they loved us. Their love was silent; it was tough love that taught us to survive. But everything they strived for and everything they encouraged us to do to better ourselves told us how much they truly loved us.

Their rules and discipline never changed for us, whether we lived at home or were grown and gone away. Give or take, right or wrong, they were the parents and we were the kids. Being grown meant being on your own; but, even so, if you were in their house, you respected and obeyed their rules. Pop never let us forget that although he wasnt book smart, he could rely on his mother wit, which made him smarter than we would ever be. He believed if it wasnt broke, you dont fix it: finding fault meant looking for trouble; fixing trouble took time; and time lost was time you could never get back. As kids growing up, our biggest challenge was to have patience and take one day at a time, realizing how important time was.