This book is dedicated to my late wife, Iqbal, who battled leiomyosarcoma with fortitude and equanimity till the end

Preface

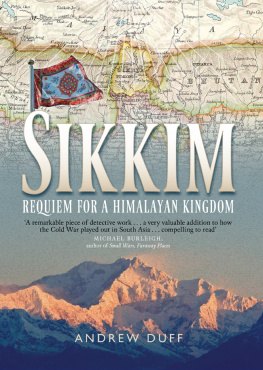

I t was in August 1973, a day before I left for Gangtok to take charge as the Officer on Special Duty (Police)OSD (P)that I called on the legendary Rameshwarnath Kao (also called R.N. Kao), the then head of Indias external intelligence agency, i.e. the Research & Analysis Wing (R&AW), which he had founded just five years ago. My visit to his South Block office was short and brief. Kao asked me if P.N. Banerjee, then joint director, Calcutta (now Kolkata), and Ajit Singh Sayali, my predecessor in Gangtok, had briefed me adequately about the requirements of the job. I replied in the affirmative. He then told me that I had been hand-picked in consultation with Banerjee for a very important operation and that he was confident I would be able to live up to his expectations. I was also told that though I would be the man taking decisions to handle unforeseen developments, Banerjee and he would always be there to help me in every way required. Thanking Kao for the confidence he reposed in me, I promised to do everything possible within my means to achieve the desired results.

After my briefings in Calcutta and Gangtok, I had realized the historical importance of the job assigned to me. Meeting Kao convinced me further that in Sikkim I would witness the unfolding of an important chapter in Indias history. This prompted me to start maintaining a diary in which I recorded notes about important developments, events and interactions as they took place during that period. I felt that these notes would be useful reference as and when I decided to write about the merger of Sikkim with India. Despite Kaos suggestion to me in 1988 to write precisely such a book elaborating the R&AWs role in the merger, I could not undertake this project for a number of reasonsboth official and personal. From May 2011, when my wifes leiomyosarcoma was detected, my time and energy were entirely devoted to her treatment. After the initial positive response, the cancer resurfaced. She faced the ailment boldly and there was no regret or pain on her face till the end, which came in January 2017.

Meanwhile, a number of books on Sikkim had begun appearing, many of which selectively depicted the ground realities in the period leading up to and including the merger. In some cases these books sought to underplay, or even ignore, the existence of a popular grassroots-level movement in Sikkim that favoured a merger with India. In other cases, the merger itself was incorrectly labelled an annexation, conveniently ignoring the fact that it took place through a resolution passed in April 1975 with an overwhelming majority in a popularly and democratically elected Assembly. There were also instances of certain writers resorting to unsubstantiated speculation on the nature, extent and commencement of the R&AWs role in merger-related operations. That these writers were engaging in mere speculation may be gauged from the fact that they didnt even appear to be aware of the presence of an officially approved (by the Chogyal) R&AW office in Gangtokheaded by an OSD (P) to begin with.

The period immediately after the merger also caught my attention. What surprised me the most was the speed with which Kazi Lhendup Dorjis (popularly called Kazi or Kazi Sahib) hold over his party started crumbling in the immediate aftermath of the merger. Kazi, who had devoted his life for the sake of Sikkims freedom from the Chogyals yoke, was accused of selling his country (he was called a desh bechoa ) to India, by those who had lost their power, perks and privileges with this merger. In fact, Kazi and his party lost the 1979 elections to those very forces that could not secure a single seat in the pre-merger elections of April 1974.

It is in the context outlined above that I began writing this book in the middle of 2017, in equal parts to fulfil a promise made to Kao in 1988, to put on record how (and, even more importantly, why) the R&AWs operation to facilitate the merger of Sikkim with India was conceived and executed, and finally to investigate the circumstances that contributed to the rapid decline in Kazis fortunes and prestige after I left Gangtok in early 1976.

Getting to the actual merger-related operations, they were not ordinary intelligence operations in which there is a clear nexus between the source or asset and its handler, where the source is duly compensated in one way or the other for the services rendered. They were more of a collaborative effort between the R&AW and the pro-democracy and pro-reform forces in Sikkim, who were previously repeatedly let down by India due to its policy of appeasement of the maharaja/Chogyal at the cost of their democratic aspirations. The R&AW was assigned the task of undoing that historical damage by providing these pro-democratic forces a level-playing field against the all-powerful and manipulating Chogyal, at a time when diplomacy had ceased yielding the desired results. I felt I was dealing with the remnants of Sikkims freedom fighters who were unfortunately left to fend for themselves after the rest of the India attained independence in August 1947. Under the circumstances, I considered myself to be a sort of political assistant to the Kazi, sent by the Government of India (GoI) to help him achieve his lifelong dream of Sikkims merger with India. The sophistication of the operation itself may be judged from the fact that even its main targetthe former Chogyalwhom I met frequently to brief him about Tibet- and China-related intelligence matters, could not identify my link with the operation. Till the end, he and his family continued to blame the Intelligence Bureau (IB) for their troubles.

In closing, at its heart this book is a first-hand narration of what a three-man R&AW special operations team (spl ops) in Gangtok, headed by myself as OSD (P), did in response to then Prime Minister Indira Gandhis directions to R.N. Kao in December 1972, asking him to do something about Sikkim. I hope the readers find it interesting.

Introduction

T he merger of Sikkim with India in May 1975 was a historic event in more than one way. Firstly, it undid the wrong done by India to the people of Sikkim by denying them the right to accede to, and finally merge with, the Union of India through the signing of the Instrument of Accession, as was the case with the rest of the 565 Indian princely states, which like Sikkim, were also members of the Chamber of Princes and the Constituent Assembly of India, before the country attained independence on 15 August 1947.

Secondly, to protect its strategic interests in this vulnerable and heavily defended sector along the SinoIndian border, India no longer had to depend upon the whims and fancies, and the growing unpredictability, of the Chogyal who had long cherished the ambition to secure an independent status for Sikkim like that of neighbouring Bhutan. Imagine the implications of a dissatisfied, sulking or even a revolting Chogyal in the background of a Doklam-like face-off between Chinas Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) and the Indian army, with the Communist Party of Chinas Peoples Daily publication,