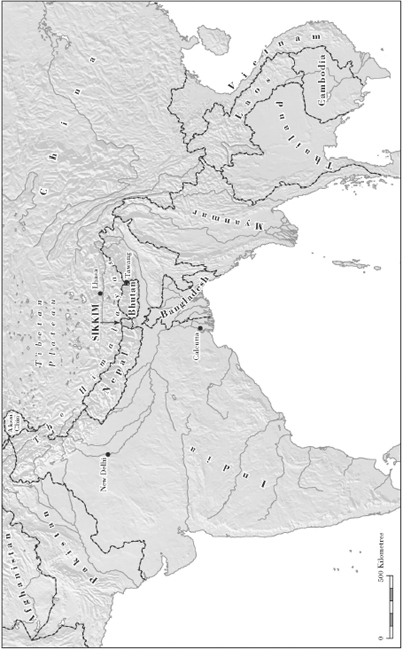

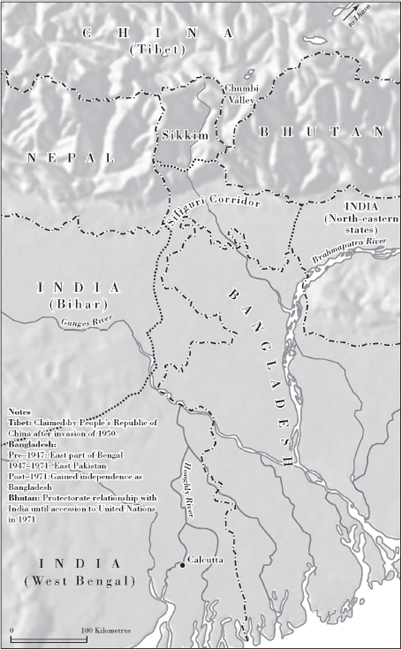

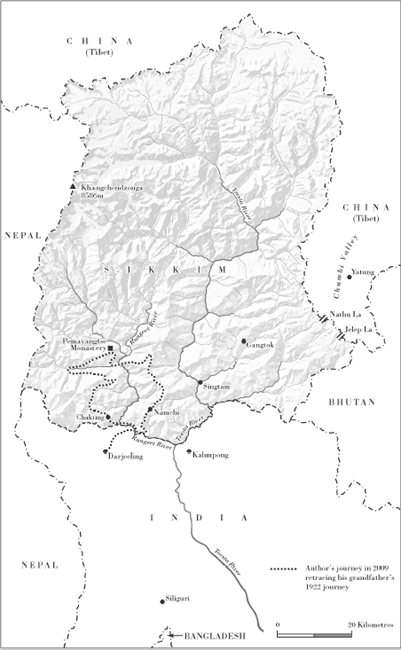

Sikkims complex geopolitical position

Introduction

April 2009, Pemayangtse Monastery, Sikkim

How much do you know about Sikkim?

The monk looked at me through the fading light, across the low table in his home on the grounds of Pemayangtse Monastery. A single bulb flickered as the electricity struggled up from the valley thousands of feet below. His maroon robes, trimmed with blue and gold brocade around the cuffs and buttoned front, contrasted with the peeling paint on the window behind him. He left the question hanging in the air as he picked up his soup bowl and slurped its contents. Through the window I could hear Buddhist chants floating out over the sounds of cymbals, horns and drums.

The words, spoken in an accented English unlike any Id heard elsewhere in India, were the first he had spoken for some minutes. I shifted uncomfortably in my bench-seat as I thought of my sparse knowledge. On the table between us I had placed a blue plastic folder from which spilled my grandfathers notes and photographs of the trek he made through Sikkim to this monastery in 1922. I supposed, wrongly, that my inheritance gave me permission to discuss Sikkim with the monk. Now it was clear I had miscalculated.

Not much, I admitted. But I would like to learn...

His hooded eyes rested on me impassively. The chanting had stopped and I could hear the steady sound of his breathing above the hum of electric current trying to feed the bulb. He picked up a book from beside him. I could just see its title: Smash and Grab: Annexation of Sikkim.

He tossed the book to me. Read this. It is banned in India. We speak tomorrow.

Looking back now, it seems a bit odd that I didnt know more about Sikkim. By the time I met the monk, the place had been in my consciousness for over two decades.

My journey to the beautiful hilltop monastery of Pemayangtse started in the 1980s. I was a teenager, living in Edinburgh. As my paternal grandparents minds began to fade, my parents moved them from St Andrews to live five doors down the road from us. I was happy: as their youngest grandchild, I had become close to them. Besides, they had around them the glow of something other, something different: they had spent most of their lives in India.

The move prompted a house clearance in St Andrews. Among the belongings that found their way into our house were a number of albums of photographs from India. I was captivated by all of them, but there was one album in particular that I would spend hours poring over. There was something physically pleasing about the weight and feel of this album. It was large and sturdy, about 18 inches wide by 12 inches tall. Inside the stout mid-brown leather cover, marked with over half a century of scratches, were two and a half inches of bound grey linen pages. It was, as my grandfather explained in a short note inside the front cover, strong rather than artistic on account of its provenance: it had been made in Gourepore, the jute mill outside Calcutta where he worked in the 1930s.

The photographs inside were absorbing: most were from my grandfathers early bachelor years in Calcutta. Others showed by grandparents newly married in the 1930s. My father and aunt also featured, as small children soon to be sent home to Scotland as the prospect of war loomed.

I wanted to talk to my grandparents about the stories behind the photographs. I felt there was something deeply unfair about the way they were declining just as I became a curious teenager. It was clear that my grandfather cared deeply for India, in his own way. Every image on every page had been carefully outlined in ink with hand-drawn geometric designs. But it was the carefully inscribed titles for each photograph that fired my imagination. I wanted to know what it felt like to jump from theback of a canoe and swim in the river at Falta, to watch the monsoon break at Parasnath, to mess around burying his best friend J. E. Osmond in sand to look like Tutankhamun at Gopalpur. I wanted him to tell me about the elephants on the tea estate in Bhooteachang, about bathing naked and picnicking on fish in the Sunderbans. I wanted to ask him about the Garhwal Himalayas, the Pindari Glacier, about places with strange names like Shillong, Kalimpong, Darjeeling, Ranchi, Phalut.

But there was one word I wanted to ask him about more than anything else: Sikkim.

Each time I opened the album, it was the first word that confronted me. On the right-hand page, encased in elaborate stencils, was a single black-and-white photograph of a river rushing under a flimsy-looking bridge. On one side of the photo in large letters was written Sikkim; on the other, Pujahs 1922. On the facing page six typewritten sheets of yellowing note-paper had been carefully glued by their edges so that they overlapped. At the top of the first sheet: Notes on a Tour in Sikkim Oct. 1922. The notes contained an account of a journey a holiday walking a ten-day circular route into the Sikkim Himalaya. The first eight pages were photographs of that journey, made when my grandfather was only 22 and had been in India for less than two years, but there had been other journeys through Sikkim, too, after my grandparents had married in 1929. There was a trip in 1932, again in 1934, and perhaps most remarkably one in 1938, when they trekked together over a 14,000-foot pass into Tibet.