PRAISE FOR HIMALAYAN PLAYROUND

Exploration of peripheral ranges and lesser peaks in the Himalaya has, if anything, waned over the last 30 years. Todays generation appears addicted to the standard itineraries offered up by commercial expedition companies. Mera Peak, Island Peak, Ama Dablam, Cho Oyu, Everest ... these few iconic peaks see thousands of visitors every year, while the other 99% of Himalayan and Karakorum mountains remain untrav-elled. Yet with modem means of travel many fabulous and remote ranges can be penetrated within the time frame of an annual holiday.

In this short but engaging book Trevor Braham reminds all those who flock to the honeypots of the Khumbu that there is a world of endless fascination beyond. Braham recounts his post-war journeys in Garhwal, Sikkim, Karakorum and the North-West Frontier, spanning the period 1947 to 1972. None of these trips achieves spectacular results. Indeed Brahams wanderings are notable for their lack of success! And herein lies the charm of the book. The spirit of mountain travel is what really counts to Braham. He grasps every brief period of leave from his job in the sub-Continent to visit new valleys and obscure peaks, sometimes with a team, but often with just a single companion.

The accounts convey the flavour of Himalayan travel after partition and independence. The protagonists had to accept lengthy delays in getting permits. A week spent idling at the doors of bureaucracy in Islamabad was not unusual. By contrast, a great deal of privilege and courtesy awaited the traveller once the gates were opened, not just loyal porters but also armed escorts in volatile regions.

Many of the places visited in Pakistan, such as Swat valley and Waziristan are now hotbeds of Islamic fundamentalism and terrorism, and have been off-limit to Westerners in the last decade. Braham gives us a glimpse of their culture in a less frenetic and happier time.

The narrative switches pleasingly between the human, geographical and cultural themes. There are excellent line maps and original photographs. Brahams style is perhaps a little short of vivid personal anecdote. A retrospect from a vantage of 30 years inevitably loses the sparkle of immediate experience. Nevertheless, those who aspire to a genuine mountain ethos, released from the bondage of commercial pressure and personal ego, will find these recollections highly enjoyable, and will regret only their brevity.

Martin Moran

A KNOWLEDGEABLE MOUNTAINEER LIVING IN INDIA

Trevor Braham was both far-seeing and lucky. He was at school in India and, after World War II, took a job with plentiful leave in his fathers firm in Calcutta. The element of luck was that this was the beginning of the Golden Age of Himalayan climbing and that in 1947 a prestigious Swiss expedition to Garhwal, led by the famous Andre Roch, invited a guest member from the Himalayan Club. Braham, who was living in Calcutta and had previous experience of trekking in Sikkim, got the job. He climbed Kedarnath Dome with Roch, Graven and Dittert, and returned on his own over various high passes with two Sherpas. What a wonderful start to a Himalayan career!

It established Braham as a knowledgeable mountaineer living in India and so he was invited to join several other expeditions. He was also perfectly placed to organise his own mountain trips, especially when he moved to Pakistan in 1961. The climbs in this book span in time the 30 years he was living in the east and in geographic spread from Sikkim toWaziristan, including the tragic Minapin expedition of 1958.

It was of special interest to this reviewer that he visited Spiti in 1955 with Peter Holmes, whose book inspired the reviewers expedition there in 1958. It is surprising that he has drawn his own map with sausage glaciers, when Holmes much better map was available in 1958, and my own in 1962.

In this book, Braham covers the same expeditions as in his 1974 Himalayan Odyssey, but, as an octogenarian, considers the maturity of later years has led to a deeper appreciation of the pleasures, heightening the awareness of the good fortune that has enabled me to develop a more profound relationship with mountains.

It has certainly led in this short book to a vision of enjoyable climbing on the lesser Himalayan peaks, climbing in a way that has become much more difficult since the mountains became draped in bureaucracy and commercialism, as Doug Scott laments in the foreword. Even if you have read Himalayan Odyssey, this is a book not to miss.

Joss Lynam

Irish Mountain Log, No 89, Spring 2009

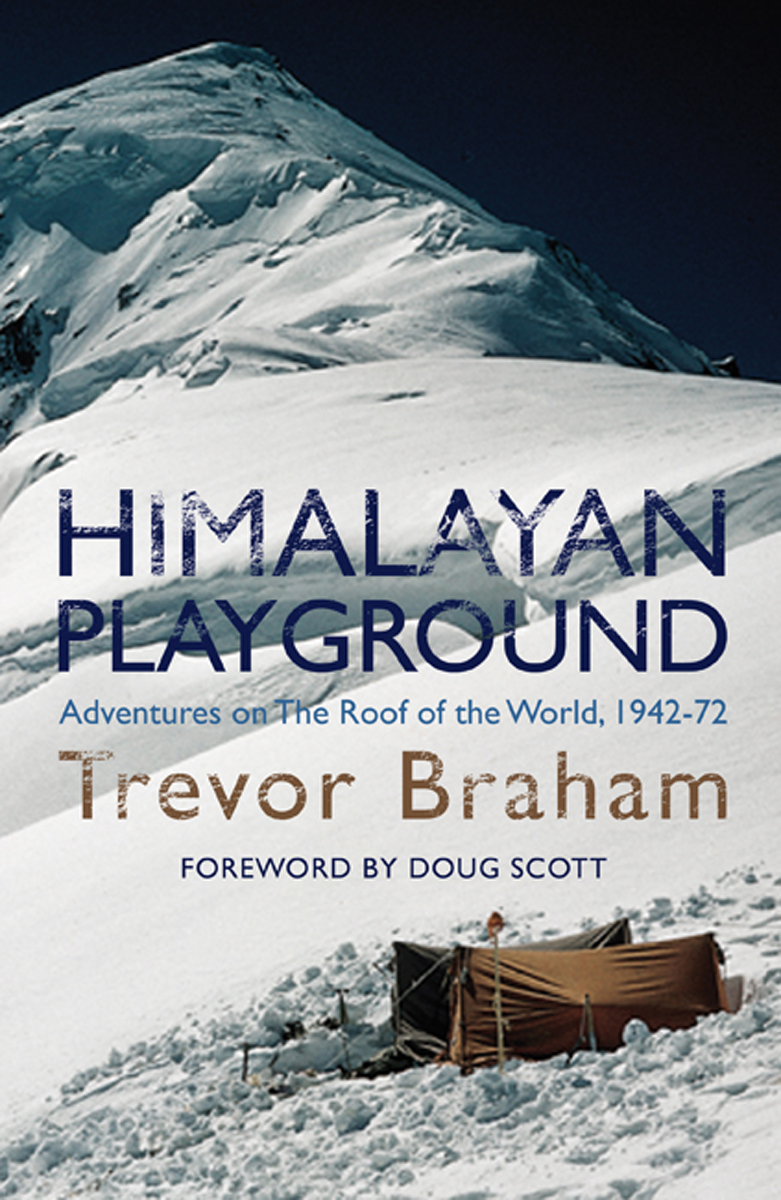

HIMALAYAN

PLAYGROUND

Adventures on The Roof of the World, 1942-72

Trevor Braham

FOREWORD BY DOUG SCOTT

www.theinpinn.co.uk

To Elisabeth

for her constant encouragement.

Also to Anthony and Michael

for their valuable support.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Apart from the picture on the front cover of Camp 3 on Minapin, taken by Dennis Kemp, and on the rear cover of the 1955 Cambridge University Expedition to Spiti, taken by Peter Holmes, all illustrations in this book are from photographs taken by the author.

The maps are based on originals appearing in my earlier book, Himalayan Odyssey, which were prepared with assistance from the Royal Geographical Society London, and have been adapted for use in this book.

Once again, I express my thanks to Sallie Moffat for the task of editing the text.

Foreword

Trevor Braham has put together another important contribution to Himalayan literature filling in the gaps in time and space historically and geographically. He shares with us his rich store of memories from a bygone age of Himalayan exploratory mountaineering. He is a link with the past as he started his Himalayan climbing before jet travel, at a time when expeditions could take up to half a year, before satellite phones and the possibility of helicopter rescue. In those days climbers were always fully committed, out of contact with family and friends and without communication to home and office. Such men were mentally and physically tough and were of a time when it was unusual for people to own a motor car, when people used to walk far more, before antibiotics, before nutritionists and personal trainers, when, in fact, it was felt somehow unsporting to train too hard. Nylon had only just been invented, plastic and closed cell foam boots had yet to appear along with the gas stove, ice screws and curved ice axes. Skill levels were lower and the dissemination of knowing what others had done before was far slower.

It was also a time when climbing was beginning to move forward after the huge setback it suffered during the Second World War, particularly on the Continent. But there was co-operation between Britain, Austria and Germany before the war and after it with the Swiss, as on Everest in the early 1950s. There were the beginnings of a proper appreciation of what it means to climb really high and the effect on the body. The physiologist Griffith Pugh had demonstrated on Everest that rehydration was just as important as proper acclimatisation.

How wonderfully fresh and adventurous it must have been for the 20-year-old Braham travelling through the Himalaya in 1942 as a young soldier on leave during the Second World War and how wonderful to have Sherpa companions whom he had read about in the pre-war Everest expedition books. It is reassuring to find a climbing author not entirely consumed with himself while acknowledging not only who he was with, but also the vital contributions played by those who went before. There is a lot of useful, historical fact introduced into the narrative that is accurate, as one would expect from a former Honorary Secretary of the Himalayan Club, later the editor of the