M AKING B OURBON

MAKING BOURBON

A Geographical History of Distilling in Nineteenth-Century Kentucky

K ARL R AITZ

Cartographic Design and Production by Dick Gilbreath, Gyula Pauer Center for Cartography and GIS

Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged to experiment with user settings for optimum results.

Copyright 2020 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Unless otherwise noted, photographs are from the authors collection.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Raitz, Karl B., author.

Title: Making bourbon : a geographical history of distilling in nineteenth-century Kentucky / Karl Raitz.

Description: Lexington : University Press of Kentucky, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019045519 | ISBN 9780813178752 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780813178776 (pdf) | ISBN 9780813178783 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Bourbon whiskeyKentuckyHistory. | DistilleriesKentuckyHistory. | Distilling industriesKentuckyHistory.

Classification: LCC TP605 .R36 2020 | DDC 338.4/766352dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019045519

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America

| Member of the Association of University Presses |

Contents

Illustrations

Maps

Photographs, Drawings, and Art

Tables and Graphs

Introduction

Kentucky Bourbon in Time and Place

I was born into a culture that then, as now, treasured place and geography more than time and history.

Edmunds V. Bunke

The manufacture of whisky is one of the most extensive and valuable interests of the entire Blue Grass Region. Indeed, the blue grass seems to have a beneficial effect on whisky, as it has on everything else that comes in reach of it.

William H. Perrin

In the heroic age our forefathers invented self-government, the Constitution, and bourbon, and on the way to them they invented rye. Our political institutions were shaped by our whiskeys. They are distilled not only from our native grains but from our native vigor, suavity, generosity, peacefulness, and love of accord. Whoever goes looking for us will find us there.

Bernard De Voto

Kentucky distillers have produced alcohol spirits for more than two centuries. The frontier craft began by utilizing simple equipment and traditional techniques to convert Indian corn into a clear spirit sometimes called white whiskey.

To see a contemporary distillery from a distance is not to understand how it works; how it relates to its site, employees, or neighboring properties; or how it evolved to become a tangible artifact. While the distillery is a largely anonymous place to the casual observer, its image and its product have come to represent the industry, and the state of Kentucky, to the world.

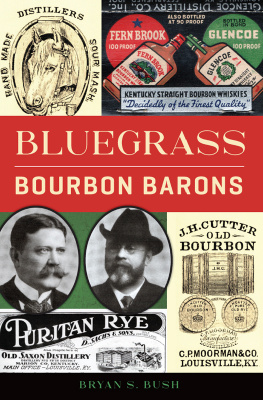

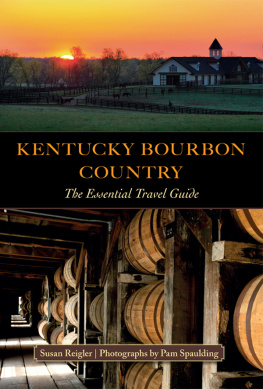

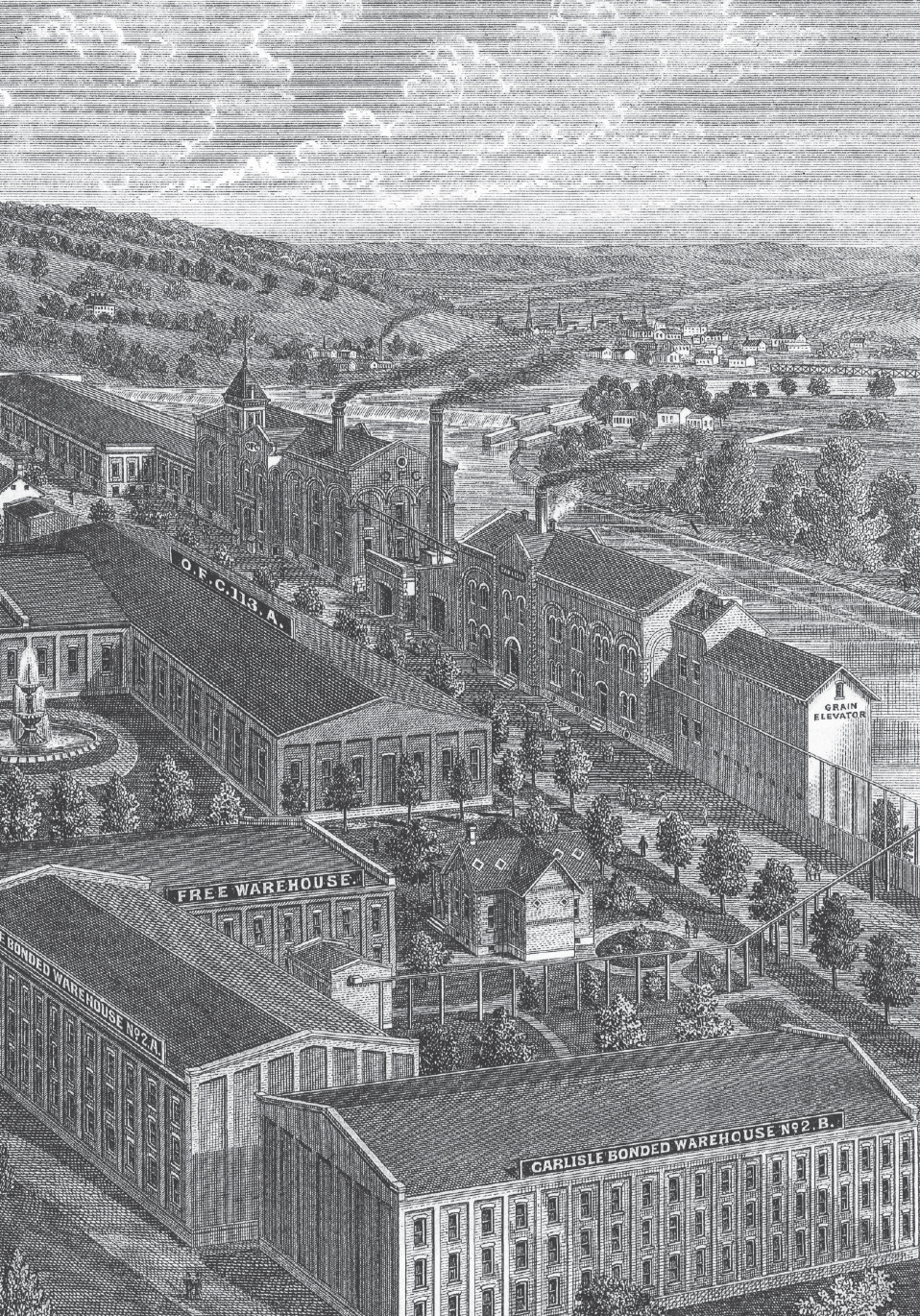

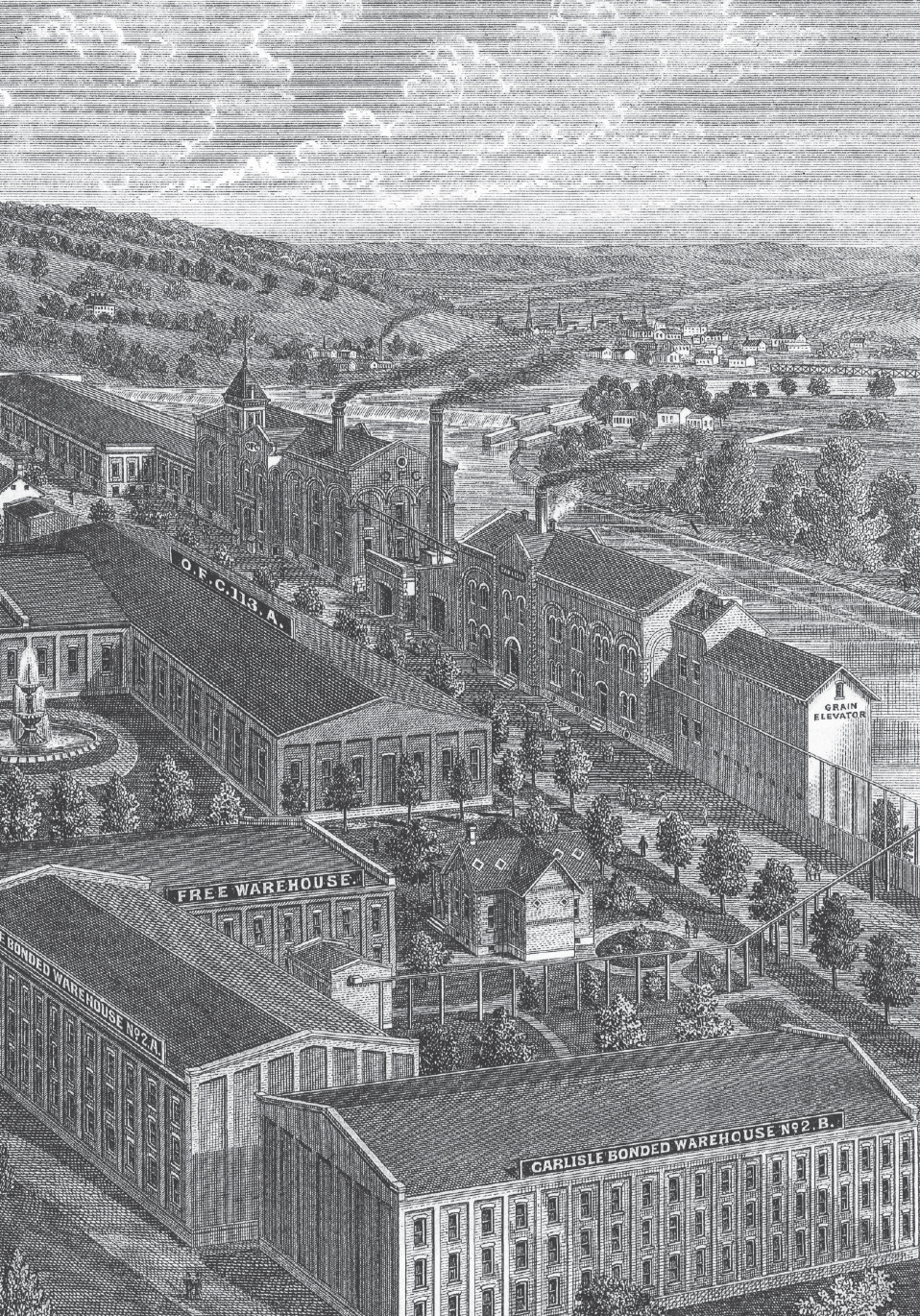

The place and landscape of distilling have always been important elements in promoting and advertising Kentucky bourbon. Nineteenth-century advertisements and bottle labels prominently featured the name of the county of origin and often included real or fanciful images of operational distilleries. Bourbon producers have long revered traditional distilling techniques. Distillers followed proven recipes and branded their whiskeys as Old, as in Old Times and Old Log Cabin. Or their brands alluded to historical places and personages, such as Rolling Fork and Evan Williams. While many manufacturers of consumer goods tout their products as new and improved, contemporary bourbon advertising campaigns continue to emphasize tradition and heritage. Perhaps more than any other industry in America, the Kentucky bourbon whiskey business has purposely maintained its traditions and methods. Bourbons heritage has its own folklore and founding narrative. Its heritage is iconic; it is tangible; it is the essence of the industrys legendry. And heritage is marketable. Present-day distilleries welcome tourists with guided tours, visitors centers, and museums. While marketing to tourists is a comparatively new phenomenon in the bourbon distilling business, the industry image presented to visitors is infused with tradition. Indeed, many distilleries operate, at least partially, in old buildings, a venerable legacy of the past. Distillings most valued images, those depicted in museums, on tours, and in advertising, are taken from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuriesthe era when this frontier craft became a modern industry.

The general historical outline of Kentucky distilling has been well documented, and there is no need to duplicate those studies. Rather, the purpose here is to examine the geographic history of the transformative nineteenth century, when distilling changed from artisanal craft to large-scale industry, and to examine how distillers created the signature distilling landscape that remains at the core of the contemporary industrys identity.

Distilling has long been associated with farming and milling. It also has supply linkages to the timber and cooperage industries, which provided staves and barrels; the copper mining and smithing industries, which contributed still equipment; and the pottery and glass industries, which provided the stoneware jugs and bottles in which the product was sold in the retail market. Raw materials and supplies arrived at distilleries by road or by railroad, and perhaps by river in some locations; the finished product was transported to customers first by packhorse trains, then by wagons and river flatboats, and later by steam-powered conveyances. All these thingsthe farms and mills, the lumberyards and cooperage shops, and the turnpikes, railroads, and steamboatscontributed elements to the distilling landscape.

As a manufacturing process, distilling is simple in concept and complex in execution. Distilling is a serial or stepwise operation in which raw materials are processed to make raw alcohol spirits that are further transformed by special aging techniques before eventually yielding a potable and salable product. Distilling begins with enzymes in malted barley that convert the starch in a slurry of water and milled grain into sugar. Cooking the mixture produces a mash, which the distiller ferments; adding yeast converts the sugar into alcohol. When fermenting is complete, the product is referred to as distillers beer. The liquid then passes through a two-stage distilling process. The first stage produces a low wine, which is then redistilled in the second stage into a high wine, often in a traditional copper pot still or doubler. Complexity arises because the distiller must work with precision and speed, using varied recipes. Corn mash requires a different cooking temperature than rye or wheat mash. Malted barley enzymes lose their effectiveness if the mash is too hot. Yeast requires oxygen to work effectively and may die if the mash pH is too acidic or too alkaline or if the mash temperature is too high. The selective movement of raw materials and the precise control of the distilling process in an industrial distillery require a dense rookery of conveyors, vats, pipes, pumps, valves, gauges, and filters. This assemblage demonstrates that the modern distilling process is intricate and demands exacting attention to detail.