Contents

This eBook is licensed to Simon Karoly, simonkaroly123@gmail.com on 04/19/2021

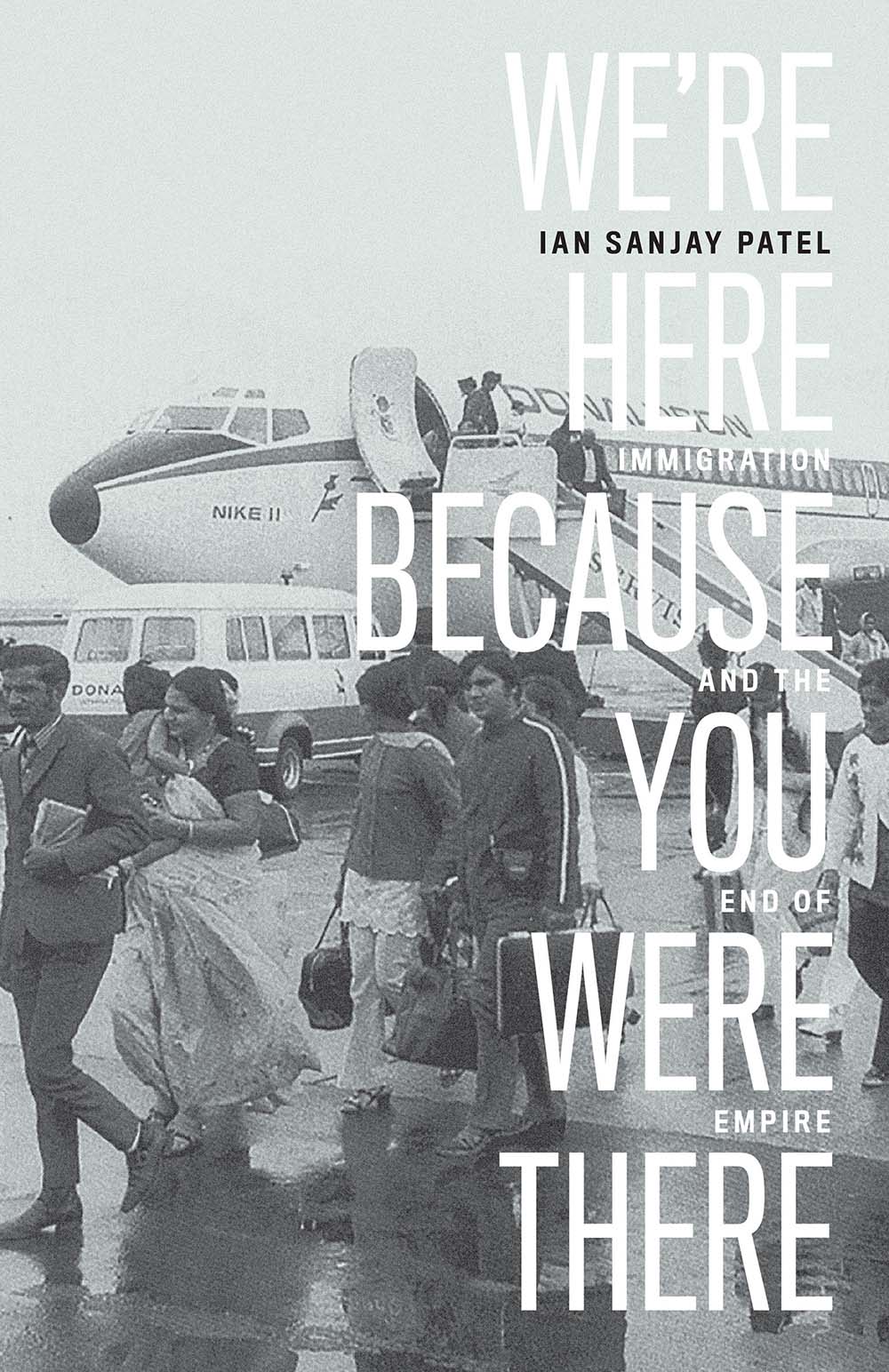

Were Here Because

You Were There

Immigration and

the End of Empire

Ian Sanjay Patel

This eBook is licensed to Simon Karoly, simonkaroly123@gmail.com on 04/19/2021

First published by Verso 2021

Ian Sanjay Patel 2021

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-767-8

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-768-5 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-053-2 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020948731

Typeset in Minion Pro by MJ&N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

This eBook is licensed to Simon Karoly, simonkaroly123@gmail.com on 04/19/2021

For Shantaben Patel (19232015)

This eBook is licensed to Simon Karoly, simonkaroly123@gmail.com on 04/19/2021

Contents

____________

This eBook is licensed to Simon Karoly, simonkaroly123@gmail.com on 04/19/2021

At the time we were Black and Asian, we ticked the Black and Asian box on the medical forms, joined the Black and Asian family support groups and stuck to the Black and Asian section of the library: it was considered a question of solidarity.

Zadie Smith, Swing Time

Those natives were never meant to come here and live next door.

Race relations professional, London, 1972

Beneath every history, another history.

Hilary Mantel, Wolf Hall

This eBook is licensed to Simon Karoly, simonkaroly123@gmail.com on 04/19/2021

________________

We are here because you were there. These were the pithy words of the writer Ambalavaner Sivanandan, born in the British colony of Ceylon (later renamed Sri Lanka), who migrated to Britain in 1953. His words addressed a British state that had denied an incontrovertible history about why so-called immigrants were now in post-war Britain in greater numbers than ever before. Here meant Britain; there meant former British colonies. If poorly understood, there was a direct relationship, Sivanandan suggested, between the British empire and post-war migrations to Britain. Domestic British history had been separated from British imperial history, and from this false separation, confusion about and rejection of post-war immigrants had been allowed to spread.

If immigration did not exist, it would have to have been invented. No term better than immigrant helped convert those post-war migrants into the insinuating ghosts of a colonial world supposedly separate from domestic British life. To this day Britain remains deeply equivocal, both socially and politically, about exactly what happened with respect to immigration, why it happened, and whether its happening was a welcome thing. This book animates the four corners of Sivanandans aphorism, unearthing the you, the we, the here and the there, to reveal their overlapping, plural combinations of place, experience and encounter.

Overused, manipulated and exhausted, immigration somehow remains one of the most compelling words in the vocabulary of social and political life. We all know that immigration is complicated, controversial and important and privately we each hold views on the subject that are more than likely firmly made up. Whether described in social, economic or ethical terms, immigration seems never to fail to command high emotion to meet an apparent need for symbols and scapegoats, often signalling either progress or decline, depending on the observer.

Few words better stir a sense of national identity and destiny than immigration. The immigrant, by definition, does not belong to the nation-state in which she resides. The imagined idea of a nation-state a people belonging to an ancestral territory under a state that protects both finds its negative image in immigration. The claim that some do not belong only brings the belonging of those included in the nation-state into greater relief. One of the primary international prerogatives of the state is the ability and discretion to define who is a citizen (a national) and who is not. Yet British national identity has been less influenced by the nation-state than by the claims of its political traditions and the perceived uniqueness of its political institutions above all the rule of law that helped give purpose to the empire. The British national experience of immigration after 1945 was therefore caught between an indistinct nation-state and a conspicuous imperial past and present.

Immigration is also a byword for race, and for ideas about who is and who is not native to the nation or, in Britains case after 1945, native to the imperial heartland. In many ways, the primary domestic encounter of British political elites with questions of race occurred in the 1960s, when transformative immigration legislation was devised for the first time. Despite the presence of non-white people in Britain in smaller numbers for hundreds of years, post-war British politicians and officials saw the problem of coloured immigration to be a new, unique, at times even eschatological threat.

The origins of the non-white people who migrated to Britain during the post-war period ranged from the Caribbean to Africa, South Asia and the Pacific. It is generally understood perhaps more by intuition than concrete knowledge that they held a form of British citizenship, or at least had the right to enter, live and work in Britain, despite the persistent referencing of them as immigrants. The so-called Windrush scandal that erupted into the media in 2018 centred on reports of people who had migrated as children from the Caribbean in the post-war period, and who were now facing deportation or had been deported. It was bewildering: surely they already had British citizenship? How could their claim to citizenship have been finessed away by legislation? It turned out to be fiendishly complicated something to do with old nationality legislation in 1948, the ugly acronym CUKC (a citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies), and the key date of 1 January 1973, when the 1971 Immigration Act came into force. Confused? Perhaps that was the point.

In Britain, immigration has been conceived as a domestic problem, cloying and claustrophobic. To reckon with post-war immigration in Britain, one steps into a tightening circle, its air stifling, until one is ultimately in the same room as Conservative politician Enoch Powell, hearing his rivers of blood speech on the first floor of a hotel in Birmingham in 1968. This book is about getting more historical oxygen to our understanding of post-war immigration in Britain. Following Sivanandans words, this means more than anything else extending our horizons beyond domestic British history. From its origins in Britains white-settler colonies to its post-war incarnations, immigration has been as much an international as a domestic problem for British political elites.