Contents

vii

ix

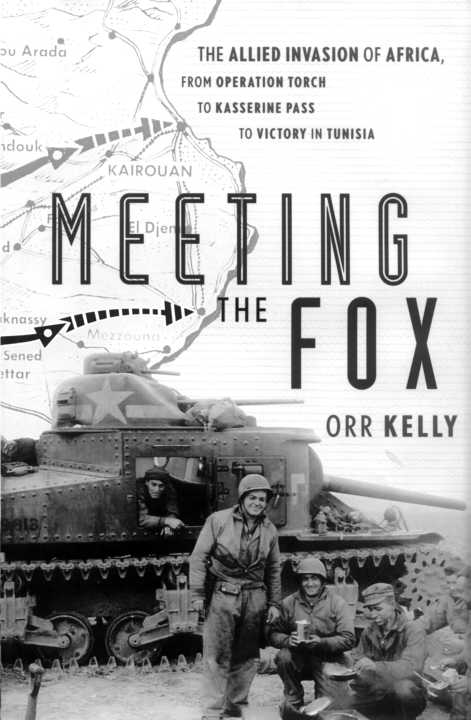

PART ONE THE LONG WAY TO BERLIN

PART TWO MEETING THE FOX

PART THREE VICTORY IN TUNISIA

Maps and Illustrations

Maps

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Research for Meeting the Fox took me to half a dozen archives and libraries. It also took me to the battlefields of Tunisia. Most writers routinely give thanks to a spouse for help, although I suspect the help often involves little more than keeping the kids quiet while the writer communes with his or her muse. In this case, far more than the usual expression of thanks is due to my wife, Mary, for her help during our Tunisian trip.

Acting as navigator, she guided us to the unmarked scenes of battles in rural Tunisia far from the normal tourist routes. When my pocket was artfully picked on our first day in Tunis, she came up with a credit card that was not linked to the ones I had lost and permitted us to continue our research trip. And she proved helpful and supportive even after I drove about ten yards too far on a road in southern Tunisia-just far enough to mire our car to its chassis in the Saharan sand.

My friend Kathryn W. Gest, executive vice president of Powell Tate, which represented the government of Tunisia, put me in touch with Bochra Malki of the Agence Tunisienne de Communication Exterieure in Tunis, who helped me get in contact with Tunisian officials. Nejm Lakhal of the Tunisian Embassy in Washington also helped with contacts in Tunisia.

At the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, I found a great wealth of material on the campaign in North Africa. The records there include not only the after-action reports written in the field, but also the maps and overlays used by the troops. Lifting them out of the folders where they have lain for these sixty years, one can almost feel the lingering grit from the Tunisian battlefields. Sandy Smith, an expert on the naval records, was especially helpful in guiding me to the war diaries of the ships that landed the invasion force.

The papers of many of the officers involved in the campaign are on file at the archives of the Army Military History Institute at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. Jim Baughman and Dave Keough were very helpful in providing access to those files. Down the hall, in the Institute library, Richard Baker guided me to the library's collection of monographs written by officers soon after the end of the war.

Yvonne Kincaid of the Air Force History Library at Bolling Air Force Base in Washington, D.C., and the staff of the Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama provided me with access to many Air Force records.

Aaron Haberman of the George C. Marshall Archives in Lexington, Virginia, guided me through the voluminous collection of the papers of Brig. Gen. Paul M. Robinett, which provided not only factual detail about the battles in which he was involved but an insight into the relationships of the leading American officers with each other and with their British counterparts.

I am also indebted to the veterans of the North African campaign, listed in the bibliography, who shared their memories with me in interviews, gave me access to their diaries and memoirs, and in a number of instances, lent me books, many of them out of print and otherwise unavailable, from their personal collections.

Special thanks are also due, for reading my manuscript and offering a number of valuable comments, to the Rev. Bernard Hillenbrand and Morton Lebow of Washington, D.C., two veteran World War II infantrymen; Col. Robert J. Berens of Springfield, Virginia, who served as a noncommissioned officer with the British Commandos and the American 34th Infantry Division in Tunisia; Col. William R. Tuck of Houston, Texas, a tank veteran of North Africa; and J. Frank Diggs of Arlington, Virginia, who fought in North Africa, was captured in Sicily, and has recently written his own account of life in a German prisoner of war camp.

Essential to making this book possible was the work of Mike Hamilburg, my agent of many years, and Stephen S. Power, my skilled and perceptive editor. At one point, due to the vagaries of the publishing business, Stephen almost got away, but we managed, thankfully, to hang onto him.

Introduction:

Visit to a Forgotten Cemetery

The guidebook to Tunisia warned us: "The detour out to the war cemetery ... is only for the dedicated."

For my wife, Mary, and me, the route to the cemetery is no detour. The North Africa American Cemetery itself is our goal.

Several years ago, in the course of research for my history of the Air Commandos, From a Dark Sky: The Story of U. S. Air Force Special Operations, I came across an Air Force oral history interview with Col. Philip Cochran, who was instrumental in putting together, in Burma, the first air commando operation during World War II. In the interview, he described what happened in Burma, but he also gave a vivid description of his experience leading a fighter outfit in North Africa, in the first confrontation between American and German forces.

His account of those desperate early days stayed in my memory, piquing my curiosity about that almost-forgotten six-month battle. It would eventually become the genesis for Meeting the Fox. It is curiosity about those early battles that has, in a sense, made us among the few "dedicated" visitors to this out-of-the-way cemetery.

In our search for it, we drive along the Mediterranean coast east of the city of Tunis past the disappointing ruins of Carthage and the picturesque village of Sidi Bou Said, its sparkling white buildings trimmed in blue, until we find a sign pointing the way up Rue Roosevelt.

The parking lot, with space for perhaps a hundred cars and several tour buses, is empty. The only sound is that of the large American flag flapping in the ocean breeze atop a tall flagpole.

An English-speaking Tunisian emerges from the office and invites us in to sign the guest book. His is a lonely job. By his estimate he sees perhaps 3,000 visitors a year-about eight a day. But some days there are none. Most of the visitors come in groups from visiting U.S. Navy ships or an occasional cruise liner. The official U.S. Battle Monuments Commission annual reports put the number of visitors higher: 7,822 in 1997 and 9,163 in 1998. Even accepting those larger numbers, the North African cemetery is a neglected monument to the almost-forgotten crucial first battles between Americans and Germans, receiving far fewer visitors than any other World War II American cemetery.