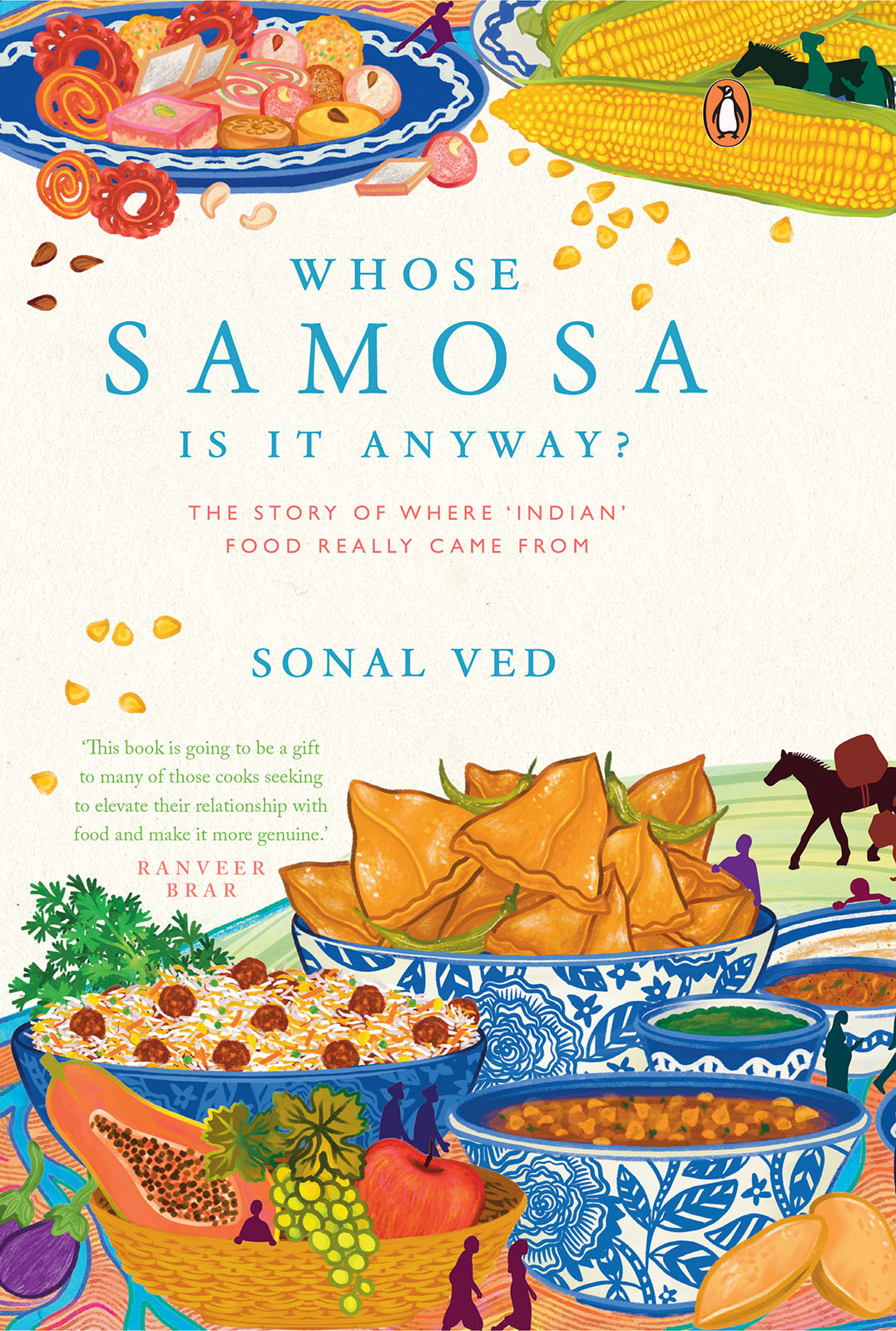

The genius of India has always been its ability to take global traditions and influences and turn them into something uniquely Indian. Indian cuisine is the best example of Indias ability to take the international and make it national. Sonal shows us, in this marvellous book, how India created one of the worlds best cuisines through absorption and assimilation.

True perspective for any cook to really have a strong relationship with food comes from understanding where the food comes from not just geographically but historically and culturally. This book is going to be a gift to many of those cooks seeking to elevate their relationship with food and make it more genuine.

This book is the need of the hour; I have waited 20 years for someone to write it.

A long overdue, refreshingly modern curiosity applied to the history of Indian cuisine. Sonal aptly brings her quirky and fun-spirited personality to the writing desk.

Introduction

My curiosity to understand Indian cuisine began in the school canteen, my first exploration of food outside of home. The house I grew up in wasnt at all an ideal prototype to study the evolution of regional food. Like many urban Indian families, we were rooted in traditionby way of Indian fasts and feastsbut an everyday meal at home was diverse, global and ahead of its time.

If there is one thing you should know about Gujarati families living in a metropolis in India, then its the fact that they gave up traditional cooking and moved to Tarla Dalal-inspired meals over two decades ago. My school tiffin seldom came stacked with rotli, daal, bhaat and shaak, or as the cool kids called it, RDBS. It was a neat show of saucy paneer enchiladas, falafel stuffed inside bajra pitas, baby corn idlis, cream cheese pinwheel sandwiches, spinach and cheese havdo, things that made my tiffin the most covetable item in classactually the second, after the back bench during a post-lunch chemistry class.

Unless I visited cousins in the heart of Kutch or Saurashtra, my exposure to Gujarati food remained the rice flour pankis that I ate at Swati Snacks, a restaurant in Bombay known for authentic Gujarati cuisine (David Chang ate here). But even those meals were tinted with flavours inspired by Bombay. Occasionally, we ate hyper-traditional dishes, like a ghee-dotted bowl of dal dhokli followed by homemade shrikhand. Summers meant mango juice-based fajeto (sounds Mexican, but its not), and aam panha. Winters meant gud papdi, lilva ni kachori and undhiyu, and the fasting season meant lots of faraal foodand that was more or less what I understood about my own regions cuisine.

In the nineties, when India was experiencing an internet boom, my table started to look different. The aloo parathas that we ate so often at dinner were nonchalantly served with an Ottolenghi dip (vaal instead of white broad beans) and amla chutney dotted on Martha Stewarts soft-shell tacos. Nigel Slaters ice-cream base was used to make our annual aam ras tub. So, to put it simply, the Ved kitchen was ever-evolving and was inspired by AmericanEuropean influences before I was able to differentiate between what belonged to my ancestors and what we had been lugging along like Hailey Beiber and her Bottega.

Food at home left me with little matter to string together and understand what Indian food was all about before the various outside influences started accumulating over the course of time.

My palate had always sought wanderlust. In school, I marvelled at my Sindhi friends tiffin that came brimming with macrolyun patata, or macaroni cooked in tomato gravy, which she ate with rotis; or at a Bohri friends malida, a wheat-based sweet dish of Afghani origin. And I wondered how this Marwari friends mom effortlessly made authentic khow suey that wasnt inspired from any cookbook but was an heirloom family recipe. My best friend, a Jain, though vegetarian on paper, skipped many vegetables. She taught me how to eat versions of potato-based dishes like pav bhaji, masala dosa and poha that did not have the root vegetable. And although I thank that experience for helping me understand the various shades of vegetarianism, I will never forgive her for making me try potato-less French fries. Yes, these were made of raw bananas.

Now that I think about it, there were many undercurrents that lay in all those school meals, those that differentiated Indian cuisine from other cuisines but also made it challenging for anyone to describe it in a line or two. I couldnt do it then, so I am trying to do it now, and that is why this book of 55,000 words.

As I began my research to understand the history of Indian cuisine, I had more questions than there were answers for. Did the European traders come before the Arab conquerors? Can you say cinnamon is an Indian spice even though it first grew in Sri Lanka on the Indian subcontinent? What are the origins of the quintessential chutney and samosa, or of the fruit punch, and how are they connected to India? Who taught us how to make ladi pav, and how did the Burmese khow suey land up on the wedding menus of Marwaris?

Experts who could answer my questions were spread across the world, and there were few books dedicated solely to this subject. As I set about to deep-dive into Indias culinary history, I realized that the process was not going to be linear. Ingredients and dishes didnt show up in the Indian kitchen in a specific order or for a reason. They just did. Indian cuisine was layered, lacked chronology, and was tinted with myriad influences that I am just beginning to unravel.

The more I found out about the Indian kitchen, the more I realized that there is no such thing as a definitive Indian cuisine. Research papers, experts, historians and the internet had a lot of data, but my attempt was to streamline these ideas andif I got luckyto make it readable for my readers.

While writing Tiffin, my second cookbook, which compiles 500 recipes from the twenty-nine states and nine union territories of India, I had concluded that it was safe to say that there are as many hyper-local Indian cuisines as there are Indian states. And even states that share borders, like Punjab and Haryana or Karnataka and Goa, have similarities and dissimilarities, some of which can only be observed if you look at their kitchens through a magnifying glass. For each region in India has its own culinary narrative that speaks through its distinct dishes and kitchen staples. Sure, there were overlaps, but each cuisine packs within itself, textures, layers, ideas and historical nuggets so that all of Indian food cannot be pigeonholed together to say that there is one Indian cuisine.