Contents

Guide

Nicholas Crane

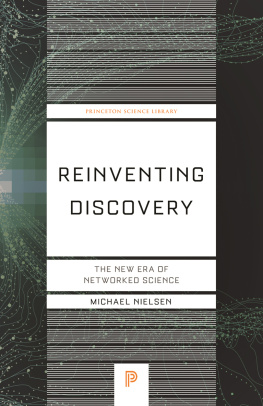

Latitude

The True Story of the Worlds First Scientific Expedition

LATITUDE

Pegasus Books, Ltd.

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2021 by Nicholas Crane

First Pegasus Books cloth edition October 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-64313-795-7

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-64313-796-4

Jacket design: Faceout Studio, Amanda Hudson

Imagery: Bridgeman Images / Getty Images

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

www.pegasusbooks.com

Only after twenty-four hours did they see daylight again; but their canoe smashed to pieces in the rapids; they dragged themselves from boulder to boulder for an entire league; finally they emerged into an immense open plain, bordered by inaccessible mountains. Here the land had been cultivated as much for beauty as from necessity, for everywhere the useful was joined to the agreeable

Voltaire, Candide, or Optimism, 1759

1

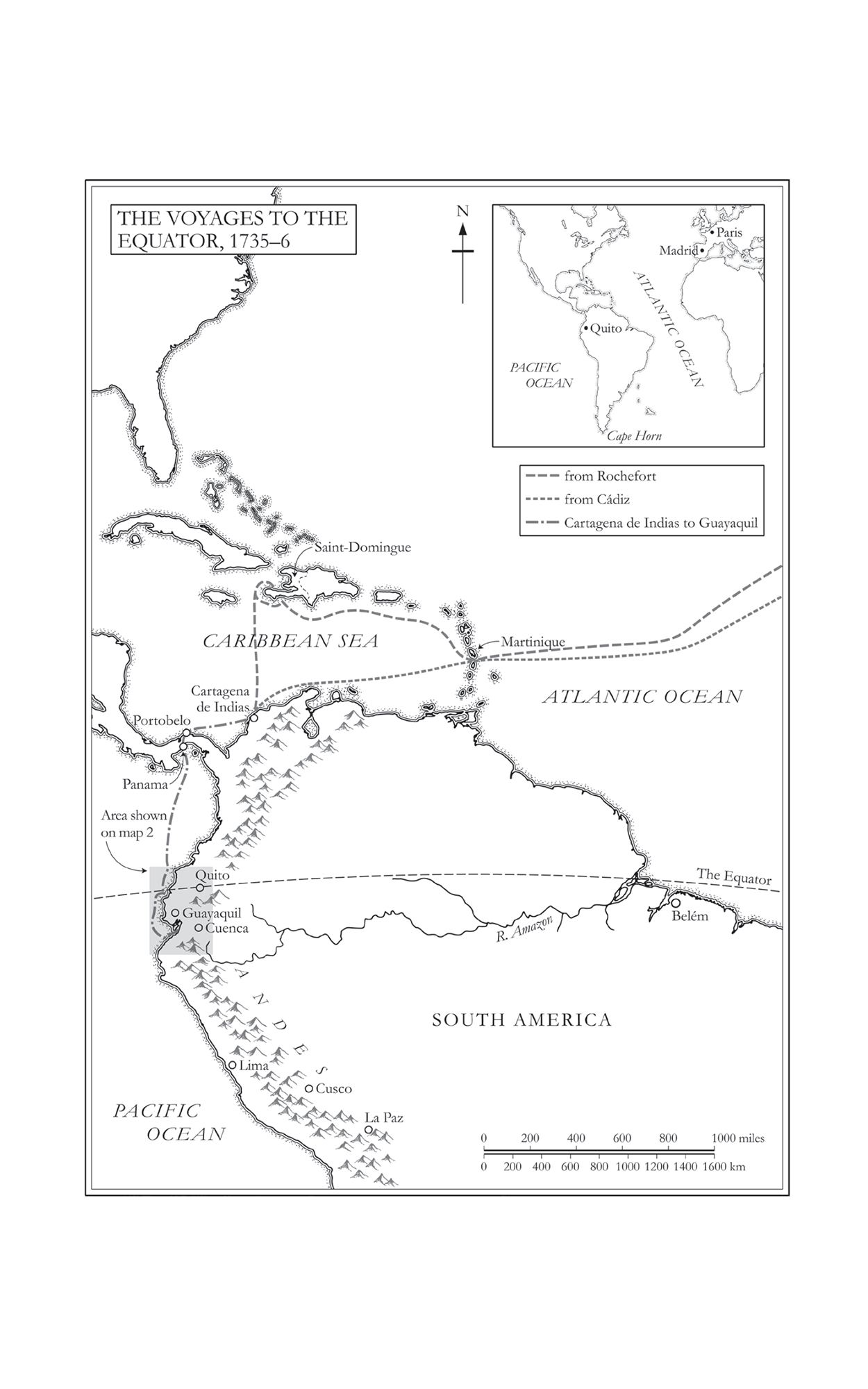

The tide was turning. Soon the moon would pull the sea down the black river. From the darkness came the gargle of water on wet mud and the eerie calls of unseen birds. On the west bank, the roofs and towers of Rochefort fused with the inky sky. A muffled clunk carried through the damp air. Boatmen were taking to their oars. The waiting was almost over. The ships hull shivered as her three masts turned across the fading stars. Morning had broken on 12 May 1735.

Portefaix was crammed with over one hundred passengers and a cargo of grain and cannon. Like most ships of the French fleet bound for the colonies, the hold was loaded to capacity. All on board hoped for a safe passage. Eighteen years was a long time for a ship to be working the seas. The 117-foot keel had been laid in Toulon back in 1717 and the hull constructed from the recycled timbers of three decommissioned warships. With 22 eight-pounder cannon on the lower deck and 22 six-pounders on the upper deck, the ship was handled by a crew of 140 men and 5 officers. They were commanded by Lieutenant Guillaume de Meschin.

The last month had been frustrating. Included on the ships manifest was the Geodesic Mission to the Equator, an unruly gaggle of universitaires, assistants and servants that had washed up on the Charente from all corners of France with an unimaginable quantity of baggage, scientific instruments and letters of authority from the king. They had more than twenty trunks of books. One of them had brought a dog. Instructions had been sent to Rocheforts navy intendant the crown official charged with the ports operation to supply the mission with swords, muskets, powder and ammunition, tents and blankets, surgical equipment and cooking utensils. More than sixty crates and trunks had accumulated on Rocheforts stone quay, together with an unpackable assortment of paraphernalia. The weight and bulk were too much for the ship. The mudbanks of the Charente and the shoals of the bay were notorious for snagging overloaded vessels. Confronted with the missions excessive baggage, Lieutenant Meschin had been obliged to unload from the hold 140 barrels of grain. It had taken two days to rearrange the cargoes. This was achieved in the presence of Professor Bouguer, who besides being a hydrographer and astronomer happened to be Frances leading expert on weight distribution in ships.

Meschin gave the order to weigh anchor and to warp the ship downriver on the ebb tide. By 10 a.m., they were moving along the sea-reach of the Charente towards the fort at the entrance to the estuary. Portefaix eased past the embrasures of le Madame, into the open water of the bay. Then the wind died. Eyes turned to limp sails. As the anchor chain rattled to the holding ground off le dAix, some of those on board wondered whether the false start was a bad omen.

Hours dragged into night. For four days, Portefaix rode at anchor. Then the wind returned and the sails were raised. Beneath taut arcs of canvas, crew and passengers watched the low shore of le dOlron slide by the port rail until they were safely past the northern tip of the island and the cautionary finger of Colberts lighthouse. Jean-Baptiste Colbert, le Grand Colbert, builder of lighthouses, roads, canals and of France, had laid the foundation stone of the French Academy of Sciences, the first learned society in France devoted to scientific research. Three of those on Portefaix were elected members of the Academy.

As Portefaix turned to the west, the deck began to heave then drop upon the ocean swell, and Professor Bouguer ejected the contents of his stomach. He had not wanted to join the mission. I had no intention of having anything to do with the enterprise, he recalled later, claiming that the weak state of his health had led to a repugnance for sea-voyages. Pierre Bouguer was Royal Professor of Hydrography at Le Croisic, the key port on the Atlantic coast of Brittany, where he trained captains and pilots for a life at sea. But Bouguer was not a natural sailor and this was his first Atlantic crossing.

Untroubled by tempests, Portefaix sailed across the Bay of Biscay towards the tip of Spain. Off the rocky snare of Cape Finisterra, the crew and passengers saw the last of Europe. With every passing watch, they settled into the routines and rigours of life on board. Compared to the security of terrestrial France, a 650-ton ship carrying 250 people was claustrophobic and uncomfortable. Bouguer and the other two Academicians distracted themselves from nausea and tedium by learning how to use their new instruments.

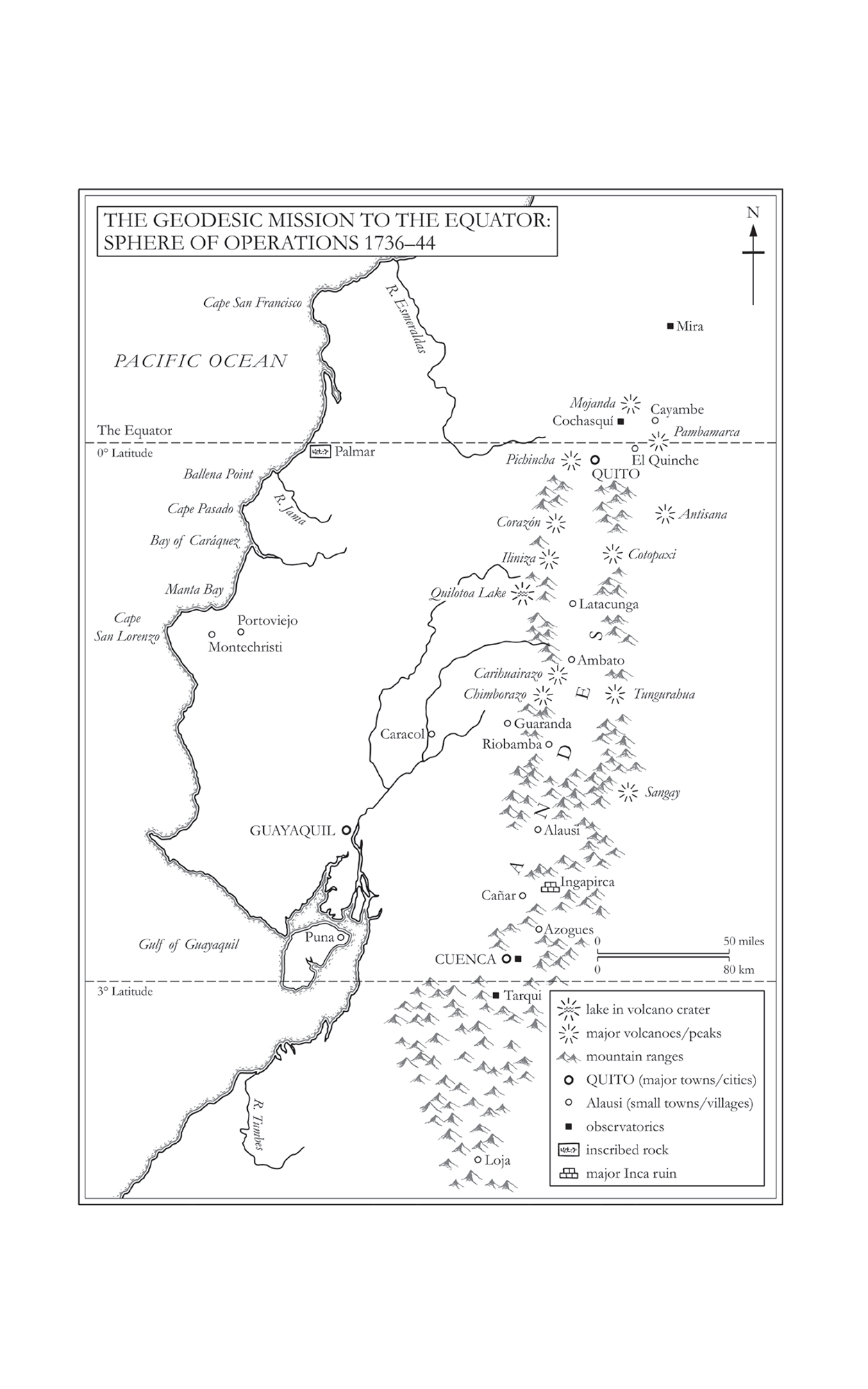

They were sailing to South America in order to answer the outstanding question of the time: What was the true shape of the Earth? Most were agreed that Earth was not a perfect sphere. But was it elongated towards the poles, or flattened? Was Earth prolate or oblate? In the elongated camp were followers of the French philosopher Ren Descartes. In the flattened camp were followers of the English mathematician Isaac Newton. In the Parisian salons and cafs frequented by the Academys elite, the Cartesians and Newtonians were fairly evenly split. Newtons theory was relatively recent and predicted that the centrifugal forces inside a fluid, rotating Earth were so great that it bulged at the equator and flattened at the poles.

It was more than an abstract debate. Without knowing the precise shape of the Earth, there could be no accurate maps or charts. The measurements provided by the Geodesic Mission to the Equator promised to make ocean navigation less dangerous and more profitable. Among those who grasped the geopolitical and economic benefits to France was the Minister of the Navy, Jean-Frdric Philippe Phlypeaux, Count of Maurepas, who was masterminding a resurgence of French maritime power and prestige. Safe navigation was essential for the navy, and a French excursion into the Viceroyalty of Peru would be able to gather useful intelligence on the Spanish colonies of South America, with possible benefits to trading and political relationships between the two European superpowers.