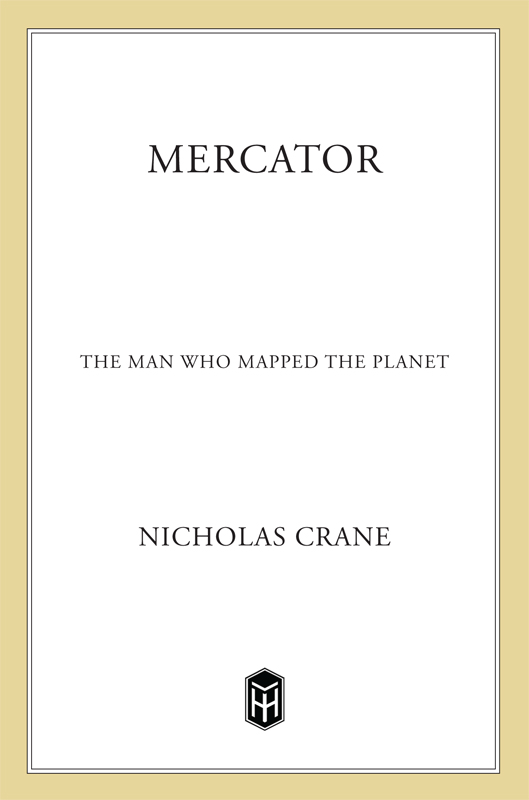

Nicholas Crane - Mercator--The Man Who Mapped the Planet

Here you can read online Nicholas Crane - Mercator--The Man Who Mapped the Planet full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Henry Holt and Co., genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Mercator--The Man Who Mapped the Planet

- Author:

- Publisher:Henry Holt and Co.

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mercator--The Man Who Mapped the Planet: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Mercator--The Man Who Mapped the Planet" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Mercator--The Man Who Mapped the Planet — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Mercator--The Man Who Mapped the Planet" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

To Annabel, and to

Imogen, Kit and Connie,

with love.

Illustrations

IN TEXT

A Personal Note to the Reader

Maps codify the miracle of existence. And the man who wrote the codes for the maps we use today was Gerard Mercator, a cobblers boy born five hundred years ago on a muddy floodplain in northern Europe. In his own time, Mercator was the prince of modern geographers, his depictions of the planet and its regions unsurpassed in accuracy, clarity and consistency. More recently, he was crowned by the American scholar Robert W. Karrow as the first modern, scientific cartographer. Mercator was a humble man with a universal vision. Where his contemporaries had adopted a piecemeal approach to cartography, Mercator sought to wrap the world in overlapping, uniform maps. Along the way, he erected a number of historic milestones. He participated in the naming and the mapping of America, and he devised a new method a projection of converting the spherical world into a two-dimensional map. He constructed the two most important globes of the sixteenth century, and the title of his pioneering modern geography, the Atlas, became the standard term for a book of maps.

No better example is required of genius arising from turmoil. Mercator was born in 1512 and died in 1594. His world was one of violent conflict, social upheaval, religious revolution and geographical discovery. He was five when Martin Luther precipitated the Reformation, and ten when the survivors of the worlds first circumnavigation returned to Seville in their leaking caravel. He knew poverty, plague, war and persecution. He was imprisoned by the Inquisition, yet patronized by an emperor. His life was one of brilliant breakthroughs and abrupt reversals.

In its telling, this is the story of the poor boy made good, the pauper who embraced the world, found fame, faced death, yet triumphed through fortitude. Variously described by his peers as honest, calm, candid, sincere and peaceable, Mercator wore and wears an aura of beatitude in troubled times. His attitude to his geographical calling was described by his friend and neighbour, Walter Ghim, as indefatigable. Mercators extraordinary longevity, eighty-two years, makes him an unusual biographical subject. Surviving for twice as long as many of his contemporaries, he was able to mature through two consecutive life-spans. In his first life, he stumbled through learning, experimentation, acclaim and catastrophe; in his second life, he withdrew to his Rhenish sanctuary and concentrated with single-minded endeavour on the works that would bring him timeless fame.

Writing Mercators Life has been a humbling experience. My motive for daring to trespass into his aura arose in part from a sense of lack. The best full-length biography of Mercator is still the volume by H. Averdunk and Dr J. Mller-Reinhard, published in German in 1914. Beyond the chapter in Karrows magisterial Mapmakers of the Sixteenth Century and Their Maps, Mercators story has never been told in full, in English. He deserves a broader acknowledgement.

Mercator is the third book in a geographical trilogy that has occupied me for the past ten years. Each of these geographical narratives has a cartographic plot. The first book, Clear Waters Rising, describes a 10,000-kilometre journey on foot along the continental watershed of Europe. The route appears on any map of Europes physical geography as a sinuous chain of mountain ranges running from northern Spain to western Turkey. The second book, Two Degrees West, was also derived from a line on a map, the line of longitude which was selected by the Ordnance Survey as the central meridian, following the decision in 1938 to map Britain on the Transverse Mercator Projection. Two degrees west runs for 578 kilometres through England, and the book describes the places and people found along that geographical cross-section. With rectilinear certitude, Two Degrees West led me to the father of modern mapmaking and this, the third of these geographical narratives.

In researching Mercator I have run up more than a few debts of gratitude. Without the British Library and in particular the reading room fondly known as Maps this book would not have been possible. The collections at the Royal Geographical Society and at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, have also been invaluable, as have those of the London Library, the National Library of Scotland and the Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp.

Many individuals gave their time and advice. For generously sharing their cartographic scholarship, I am indebted to Peter Barber, Tony Campbell, Dr Catherine Delano-Smith, Francis Herbert and Dr David Munro. (All errors in this book are entirely my responsibility and in no way reflect upon those mentioned here.) For translating essential primary sources, I am extremely grateful to Richard Bryant, Glyn Davies and William Sutton. Their care and expertise has vivified documents for the modern reader. To David Watson I extend enormous thanks for his linguistic versatility in translating disparate and seemingly arcane works relating to Mercator and historical cartography; David paid an additional price for his interest by being engaged as the books copy-editor. Thanks are also due to Tom Graves for his indispensable help in marshalling the books illustrations. While translating the book into Dutch, Jos den Bekker identified a number of inconsistencies and errors in the original English edition, now corrected, with gratitude.

Those who played a greater role than might have been acknowledged at the time include David Bannister, Hol Crane, Inge Daniels, Matt Dickinson, Luke Hughes, Colonel Colin Huxley, Simon Jenkins, Peter Van der Krogt, Roland Mayer, Hallam Murray, Stuart Proffitt, Rodney Shirley, Humphrey Stone and Louisa Young. Chris Crane was the first to read a passage from the book, but he was taken by cancer before I could finish.

Once again, Derek Johns was there at the beginning, at the middle and at the end, proving (yet again) that the trials of a literary agent begin with the sale of a promising idea. To Rebecca Wilson in London and to David Sobel in New York, I would like to extend warm thanks for commissioning the book, and to Richard Milner for guiding it through to its printed state. Finally and most importantly there is, as ever, one person who has been tested beyond normal limits of endurance. The books dedication cannot compensate for the lost years, but it does mark the return of a husband and a dad.

NC

London

March 2002

A Little Town Called Gangelt

In the summer of 1511, Emerentia Kremer fell pregnant and the harvest failed. Rye rose to its highest price for a decade and plague returned to the lands of the lower Rhine.

Emerentia and Hubert set off towards the ocean. In the Low Countries they could find food, shelter and a place to lay the baby. For several days they travelled, over the river Maas and across the heaths of Kempen, where robbers lurked by stagnant meres.

When the sandy tracks gave way to clay, spires began to pierce the sky. On these seeping levels sprawled some of Europes richest cities and towns: Antwerp and Mechelen, Louvain, Brussels, each of them arterially connected to the sea lanes of the world by the same deltaic river. It was to this river the immeasurable Schelde that the Kremers were bound.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Mercator--The Man Who Mapped the Planet»

Look at similar books to Mercator--The Man Who Mapped the Planet. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Mercator--The Man Who Mapped the Planet and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.