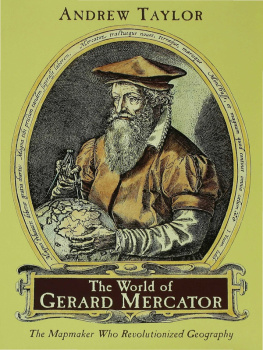

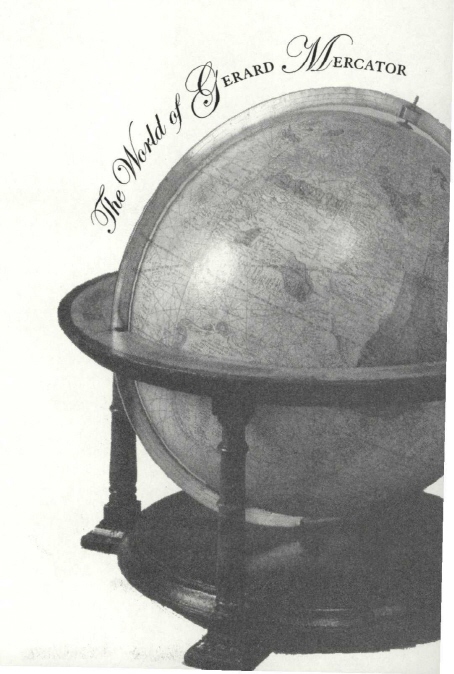

The World of

GERARD

MERCATOR

The Mapmaker Who

Revolutionized Geography

Andrew Taylor

Copyright 2004 by Andrew Taylor

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

First published in the United States of America in 2004 by

Walker Publishing Company, Inc.

Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry and Whiteside, Markham, Ontario L3R 4T8

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Walker & Company, 104 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011.

Art Credits: Used by permission of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England. Used by permission of the Bibliotheque Royale Albert I, Brussels. Used by permission of the Science Photo Library, London. Used by permission of the British Library, London, Rare Books and Maps Collections. Used by permission of the Hereford Cathedral Library, Hereford, England. Used by permission of the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Used by permission of Museo del Prado. Courtesy of Historic Cities Research Project http://historic-cities.huji.ac.il The Jewish National and University Library of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Used by permission of the National Gallery, London. Used by permission of the Bibliotheque National de France. Used by permission of the New York Public Library, Rare Books Division. Used by permission of the Royal Geographical Society, London. Used by permission of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, England.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Taylor, Andrew, 1951

The world of Gerard Mercator / Andrew Taylor,

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ).

eISBN: 978-0-802-71806-8

1. Mercator, Gerard, 15121594. 2. CartographersNetherlands Biography. 3. CartographyHistory16th century. I. Title.

GA923.M37T39 2004

526'.092dc22

[B]

2004043068

Book design by Ralph L. Fowler

Visit Walker & Company's Web site at www.walkerbooks.com

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

and all the years they have to come.

This book started with a journey to Hereford in England, where one of the great treasures of medieval Europe is on permanent display in the cathedral's New Library Building. The Hereford mappamundi sparked my initial interest in maps as a way of glimpsing the past, and my first thanks should go to the dean and chapter of the cathedral. They have custody of an irreplaceable treasure which belongs to all of us, and they make it available to anyone who cares to see it. Without that first visit, I would never have found my way to Mercator of Rupelmonde.

Because my grasp of foreign languages falls far short of Mercator's, I relied on several individuals to help me read letters and documents. Mark Riley, professor of classics at the California State University, Sacramento, was not only generous enough to translate Mercator's letters into English but also kind enough not to laugh outright at my own rusty Latin. Patrick Roberts of London similarly helped me with a number of French documents, and the late Dr, Dik ter Haar of Magdalen College, Oxford, welcomed me into his home and patiently guided me through many pages of Flemish. Any mistakes are mine; to all of them, my thanks.

In London and Oxford, the staffs of the British Library, the London Library, and the Bodleian Library were unfailingly helpful. Peter Barber, of the British Library's Maps Department, was particularly generous with his time in discussing Mercator's map of Britain with me. I had unstinting help, too, from the Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp, where it was a privilege to walk through Christopher Plantin's old workshops; from Duisburg's Kultur und Stadthistorisches Museum; the Mercator Museum in Sint Niklaas, Belgium; and the Cathedral of St. Jan, 's Hertogenbosch. A moment I shall never forget came in the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, when I first saw the map that is at the heart of the book: Mercator's world map of 1569.

Toby Eady and Mike Fishwick in London gave me the benefit of their professional help and advice in too many ways to list, and in New York, I had the good fortune to work with George Gibson. Every book needs the creative destruction of a good editor, and this volume had one of the best.

Friends helped in various ways. Tony and Jean Conyers lent me books from their library and must have wondered if they would ever see them again; Alison Roberts joined me on the trip to see Mercator's map in Paris; Grenville Byford shared his experiences as an ocean sailor to help me understand the minutiae of navigation; and Julian Bene, who spent many late nights and lengthy e-mails discussing Mercator and his life, may well recognize some of his conclusions in the book. Penny Berry came with me on that first visit to Hereford and not only tolerated an interest that changed into an obsession, but shared in it wholeheartedly, in England, Belgium, and Germany. The book that resulted is hers as much as mine.

But none of these people will object to the observation that the greatest thanks of all are due to Dr. Tim Little wood and his National Health Service team in the Hematology Department at Oxford's John Radcliffe Hospital. I owe them everything, and I don't forget.

O NE OF MY earliest memories is of myself as a small boy sitting on a wide window ledge, with my whole world laid out around me. As I turned my head, I took in the comfortable, familiar room behind me, the door into the kitchen, and the wooden sideboard up against the wall, while outside I could see down the yard toward the joiner's shop, which I knew was filled with sawdust and sharp blades. I could also see the familiar stone steps up to my front door, and another house across the way, where an old man used to sit in the doorway for hours on end, dozing.

That was about as far as my world stretched. I was aware, of course, of other worlds beyond, worlds I had heard about, half understood, or imagined for myself. Scattered among them were a few familiar islands that I had visited and knew fairly wellthe stone-flagged floor of the greengrocer's on the corner, for instance, the high wall on top of which I could walk up to the church, or the little vegetable garden where I used to watch my father as he workedbut for all intents and purposes, they were surrounded by darkness. Good things occasionally came in from those shadows outsidebars of chocolate brought by a kindly aunt, perhaps, or my mother's shoppingbut they were on the whole mysterious and unwelcoming, and if I occasionally peopled them with monsters, that was no more than any child does.

The story of discovery and mapmaking is one of pushing back shadows. The great explorers brought back undreamed-of riches and stories of unknown lands and peoples that were barely believablethe discovery of America, for instance, has been described as the greatest surprise in historybut their claims and discoveries had to be evaluated, laid out on paper, before they could form a coherent picture of the world. Much of that work was carried out by unknown figures, whose maps are lost, forgotten, or remembered only by passing mentions in ancient documents. Some were sailors or traders themselves, trying to prepare reliable charts for their own use and for those who came after them, but many were scholars who never went to sea. A few became famous and produced individual maps that stand out as landmarks in the history of the understanding of the planet. But none, in the last two thousand years, achieved as much as Gerard Mercator in extending the boundaries of what could be comprehended.

Next page