Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Originally published in the Great Britain by Hodder and Stoughton, September 2018

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

For Fredrik and Erlend, With the hope that youll see much of the world.

Oslo, Norway

59 56 38 N

10 44 0 E

Human beings took a birds-eye view of the world long before learning to fly. Since prehistoric times, we have drawn our surroundings as seen from above to better understand where we arerock carvings of houses and fields provide early evidence of this need. But it is only relatively recently that we have been able to see how everything really looks. On Christmas Eve 1968, the three astronauts aboard Apollo 8 orbited the Moon and became the first humans to see the entire Earth at once. Oh, my God! Look at that picture over there! Heres the Earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty! [] Hand me that roll of colour quick, will you, said astronaut William Anders, before taking a photograph of our planet hovering beautiful, lonely and fragile in the infinite vastness of space.

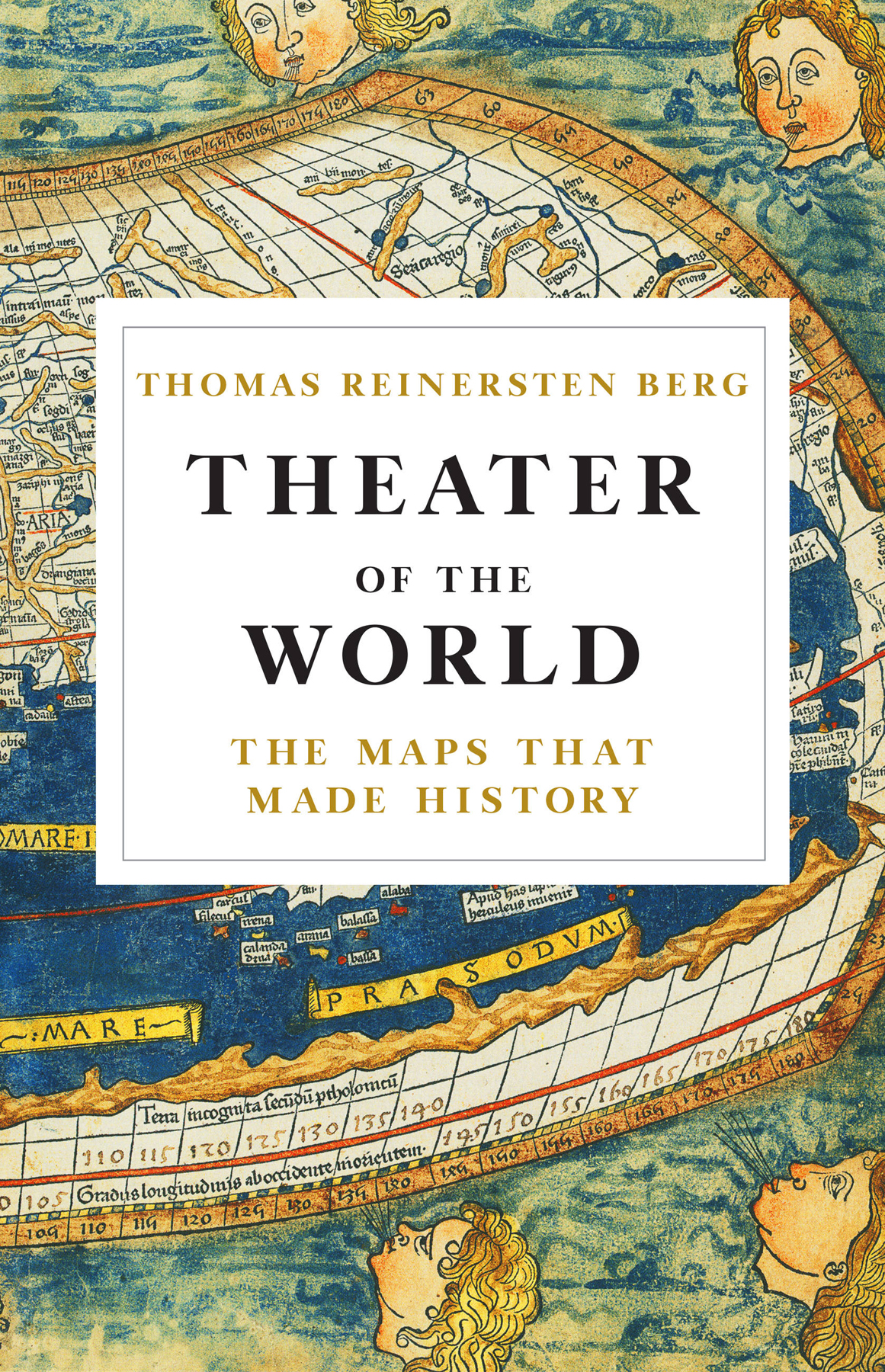

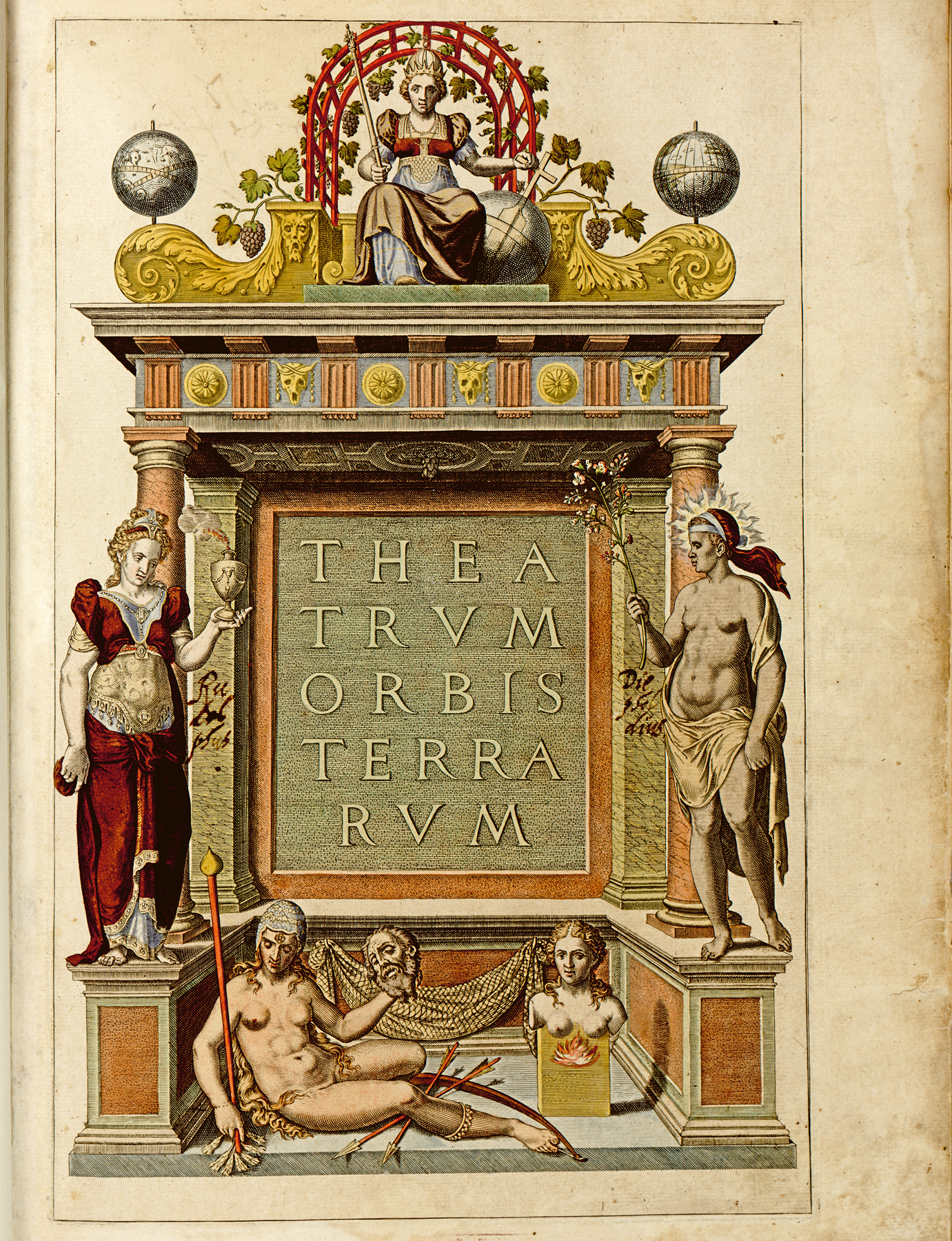

Apollo was the Greek god who rode across the sky in his chariot each day, pulling the Sun behind him. When Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius published the worlds first modern atlas in 1570, just 400 years before Apollo 8 orbited the Moon, a friend of his composed a tributary poem in which Ortelius sits beside the god in order to see the whole world: Ortelius, who the luminous Apollo allowed to speed through the high air beside him in his four-horse chariot, to behold from above all the countries and the depths that surround them.

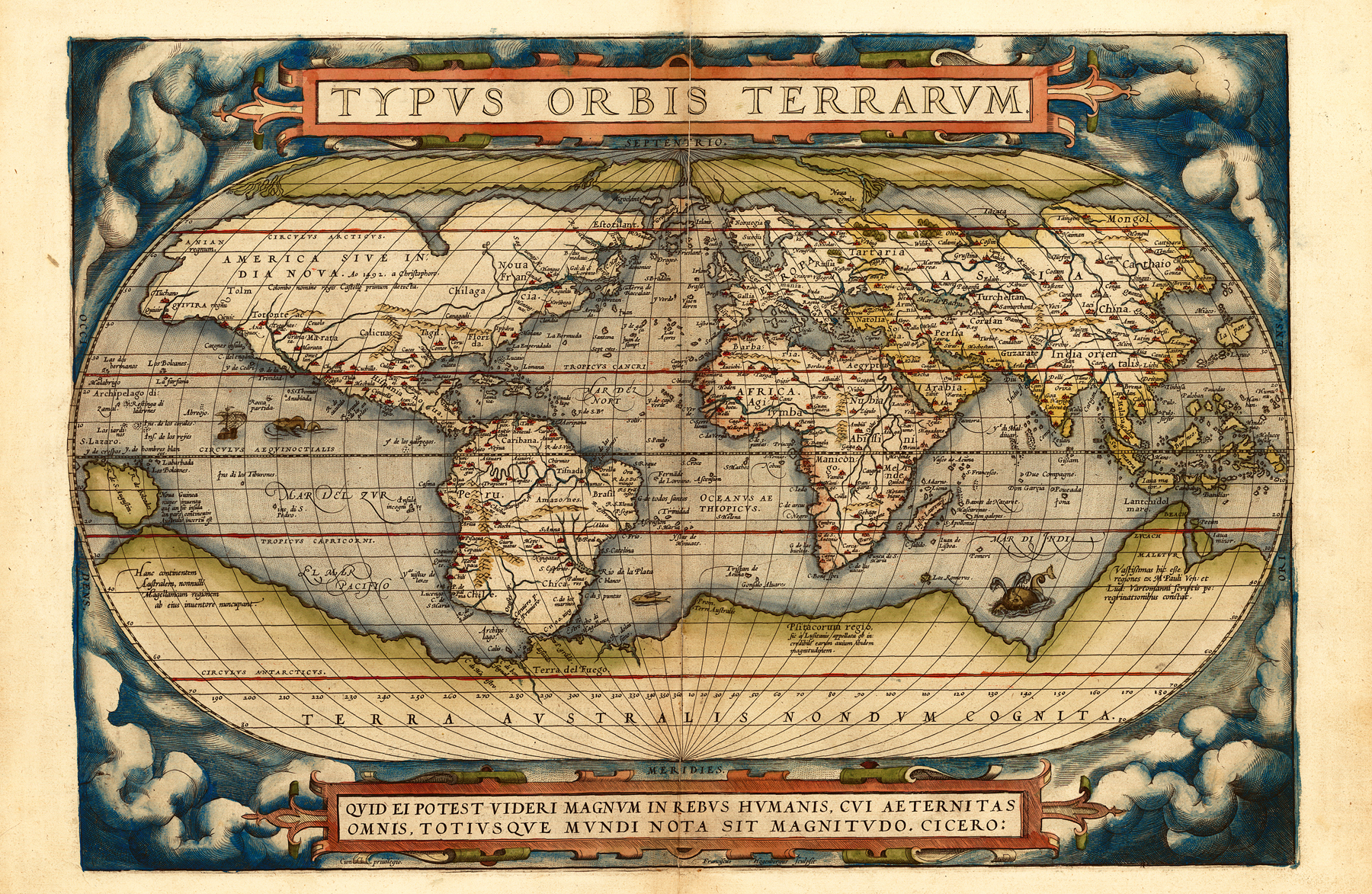

Orteliuss atlas opens with a world map, with clouds drawn aside like stage curtains to reveal the Earth. With the book open before us, we look down on Noruegia, Barbaria, Mar di India, Aegyptus, Manicongo, Iapan, Brasil, Chile and Noua Francia. Ortelius called the book Theatrum orbis terrarumTheatre of the Worldbecause he believed the maps enabled us to watch the world play out before our eyes, as if in a theatre.

Regarding the world as a theatre was common in Orteliuss time. The year after Theatrum was published, English playwright Richard Edwardes had one of his characters say that this world was like a stage,/Whereon many play their partsa formulation so admired by William Shakespeare that he used it in As You Like It some years later: All the worlds a stage,/And all the men and women merely players;/They have their exits and their entrances. Shakespeare also named his theatre the Globe.

Ortelius was no original cartographer. Nor was he an astronomer, geographer, engineer, surveyor or mathematicianin fact he had no formal education within any discipline. He did, however, know enough about cartography to understand what made a good map and what made a poor one, and with his sense of quality, thoroughness and beautyin addition to a large network of contacts and friends, who either drew maps themselves or knew others who did sowas able to collate a refined selection of maps for inclusion in the worlds first atlas.

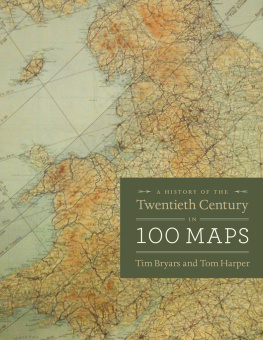

Writing a book about the history of maps is somewhat reminiscent of Orteliuss work with Theatrum. This book also builds upon the work of many others, and I have studied a considerable number of books, texts and films to identify the most important and interesting material. It has also been necessary to make certain choicesno map can cover the whole world, and no book can contain cartographys entire history, since the history of maps may be said to be the history of society itself. Maps are of political, economic, religious, everyday, military and organisational significance, and this has necessitated some difficult decisions about what to include. The hardest decisions to make have been those relating to material closest to our present time, since scarcely any aspect of society is unaffected by cartographic questions.

Throughout history, the creation of maps has been guided by value judgements as to what is worthy of inclusion. Maps have always given us more than geographical information aloneas illustrated by the clear contrast between an Aztec map of the city of Tenochtitlan, which only provides details of the rulers of each district, and Norgesatlas (Atlas of Norway) from 1963, where the publisher, Cappelen, due to social considerations, has chosen to include too many place names, rather than too few. The Aztec map reflects the hierarchy of a strictly class-based society, while the Norgesatlas represents the golden age of social democracy in which everyone must be included. Both maps were influenced by the values of the age in which they were created.

The same is also true of the writing of this book. I have chosen to give significant attention to the mapping of the northern areas of the world throughout the textnot because the peoples of these areas play any greater role in the history of maps than the Americans, Arabs, British, French, Greeks, Italians, Chinese or Dutch, but simply because this is where I come from and the part of the world in which I live. To the best of my ability, I have attempted to show how broader historical developmentsthose concerning improved surveys and new methods, new measuring instruments and a greater understanding of the ways and areas in which maps may be usedeventually reached this corner of the world and were taken into use by a poor country with a vast and difficult geography. Norway is characterised by mountains, plateaus, great forests, 25,148 kilometres of coastline and 239,057 islands, and was a Danish colony from 1380 to 1814. The country was also part of a union with Sweden between 1814 and 1905. A number of changes have been made to the original Norwegian text to make the book more accessible to an English-speaking readership.