2021 William R. Short and Reynir A. skarson

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

PREFACE

Sometime near the end of the tenth century, a man named Frai died in Sweden. His kinsmen raised a granite runestone in his memory in Denmark. Although the message carved into the stone is hard to interpret, it appears to tell us that Frai was the first among all Vikings and that he was the terror of men.

What did Frai do in his lifetime that made him so admired by his kin that they raised a runestone in his honor as the first among Vikings, yet at the same time made him the terror of men? In this book, we tell the story of men like Frai, not only about their weapons and battle-related activities but also about the inner thoughts and mindset of Viking warriors that caused them to venerate and praise activities that today we consider horrific. Along the way, we will see that Frai achieved the ultimate goal to which all Vikings aspired: orstrr (word-glory), that his name would be remembered and spoken after his death.

Viking society was a warrior society, with violence and the threat of violence a common thread shaping society and everyday life. Violence touched nearly every aspect of Viking culture.

Their myths and religious beliefs are so intertwined with violence that there would scarcely be any myths if there had been no violence. Men yearned for leaving this world after death and going to a paradise called Valhalla where they joined the elite warriors Einherjar in constant battles every day. Men were buried with their weapons, since even in death, they did not want to be far from them. The destiny of the gods is Ragnark, an enormous battle between the giants and the gods, which is foretold to end in the destruction of the world.

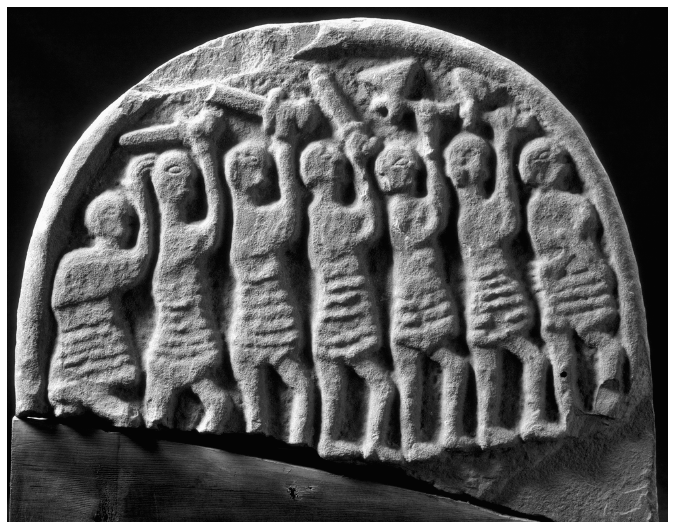

Nearly all of their stories, the sagas, are written figuratively in blood. Most, if not all, have a feud or other ongoing violent dispute as a central plot element. The surviving law codes have extensive sections on what forms of violence are permissible and what forms are forbidden. Their imagery, such as the many picture stones in Scandinavia, most often show acts of violence and men with their weapons raised ready to strike. Viking poetry used paraphrases (kennings) often based on violence and arms. Their ships, one of the great technological triumphs of the Viking age, were optimized for speed and stealth in combat, allowing for quick landings where they were least expected and for quick getaways following a raid. Even their house architecture is aligned with the likelihood of violence in and around the home, sited for strategic advantage and featuring defensive structures, hidden doors, and secret escape tunnels.

The foreign sources that chronicle the Vikings most often tell of the violence inflicted by them on the lands they visited. While these raiders were feared because they were men of terror, like Frai, they were sometimes cherishedas mercenary troops because they could be loyal like a dog, and they were sometimes admired for their courage in adversity.

This book provides an understanding of Frai and his people, based on the results of twenty years of research by our organization, Hurstwic. Our goal has been to advance the state of knowledge about Viking-related topics through rigorous testing and the use of the scientific method.

After introducing our research methods and sources, we have divided the book into several groups of chapters, each of which builds on what came before. The first group discusses topics that we believe are the underpinnings of Viking combat. Without a basic knowledge of these fundamentals, it will be hard to understand Viking people and their use of combat. These topics include mindset, empty-hand fighting, and a general introduction to the weapons of the Vikings and the place of those weapons in society.

We then move to a group of chapters that focuses on each weapon individually. They provide a more detailed look at the weapons of the Vikings and how these weapons were used: the prestigious sword; the iconic axe; the spear, the chosen weapon of inn, the highest of the gods; the bow, an essential weapon of mass battles on land and sea, and others. Our discussion will also include the defensive tools of the Vikings.

The last group of chapters delves deeper into the nature of Viking combat: mass battles on land and sea, tactics, dueling, and raiding.

We use the controversial word Vikings to describe these people, who lived in Scandinavia and moved throughout other northern European lands in the early medieval period. We make this choice for numerous reasons, but the primary one is that the alternative terms are longer, less concise, and more awkward ways to refer to these northern Europeans living in the period named for them: the Viking age, circa 8001100 CE.

Yet there are other factors at play as well. The meaning of words drifts with time, and the word Viking is no exception. In contemporary sources and in later medieval sources, the Old Norse word vkingr was reserved for seafaring men who harried and otherwise posed a threat to society, a topic discussed at length in this book. Later, the meaning drifted and was used for those deemed unworthy criminals: the bad guys of the story. Still later, the word came to mean all the Nordic people of the Viking age, and it is this sense of the word that we use in the book.

There are a number of words from the ancient Old Norse language that do not have a direct equivalent in modern English. In the text, we leave many of these words in the old language, rather than attempting to shoehorn them into an inappropriate English equivalent. Similarly, we leave place-names and personal names in the old language, using the old spelling.

The Old Norse language has several additional consonants compared to modern English, notably (thorn, pronounced like th in Thor) and (edh, pronounced like th in father). The language has many additional vowels, indicated with accents, umlauts, and ligatures. A pronunciation guide is included with the glossary. The old language is highly inflected, and we have chosen to keep the nouns in the nominative case and verbs in the infinitive for ease of understanding.

When alphabetizing personal names from lands and times that do not use family names, such as Iceland, we follow the custom of indexing using the given name and not the patronymic that follows. Accordingly, Grettir smundarson falls under G and not A.

In the interest of brevity, we cite only title and chapter (or verse, as appropriate) when we cite the core works of Old Norse literature, such as the sagas and the eddas. Print and online editions and translations are readily available for these works, and we do not wish to tie the reader to the version used by the authors in preparing this book. Chapter and verse numbers are not always consistent, and we have used the numbering from the slenzk fornrit editions where available.

![Haywood - Viking: The Norse Warrior’s [Unofficial] Manual](/uploads/posts/book/98981/thumbs/haywood-viking-the-norse-warrior-s.jpg)