2020 Stephen Millar

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, except brief extracts for the purpose of review, and no part of this publication may be sold or hired without the express permission of the publisher.

Names: Millar, Stephen, author.

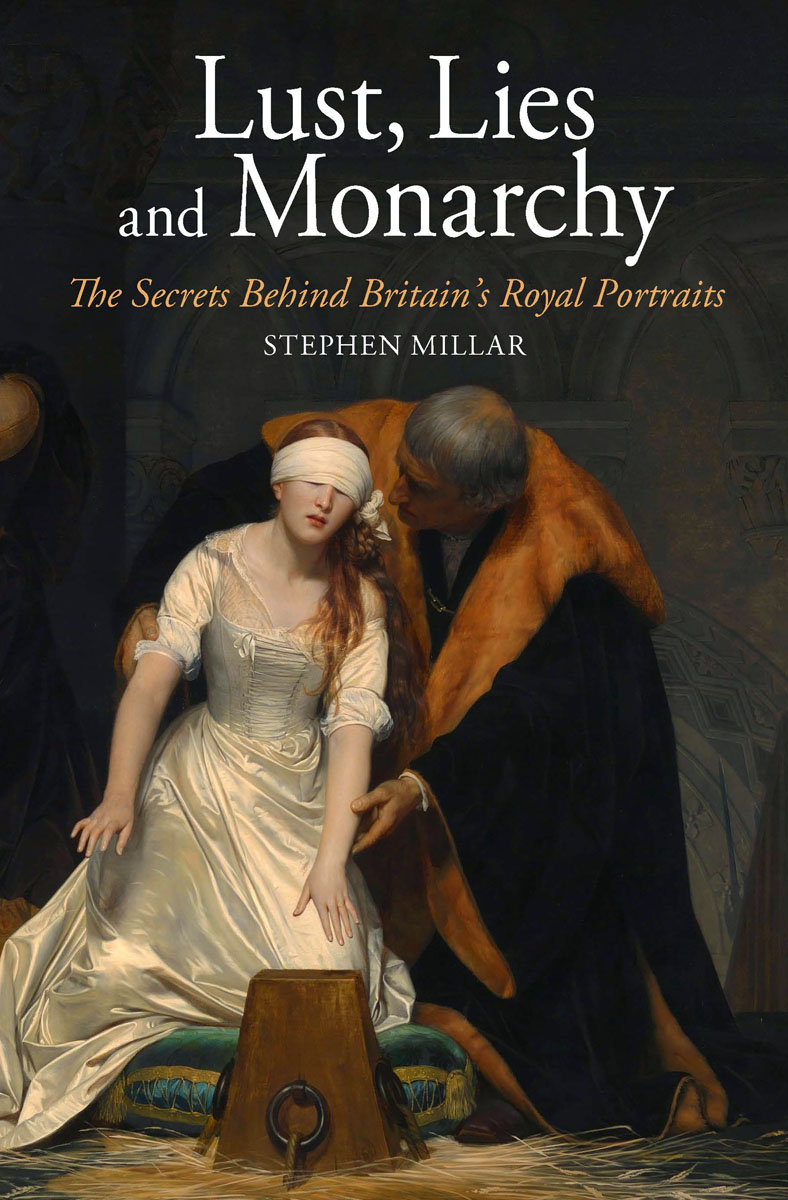

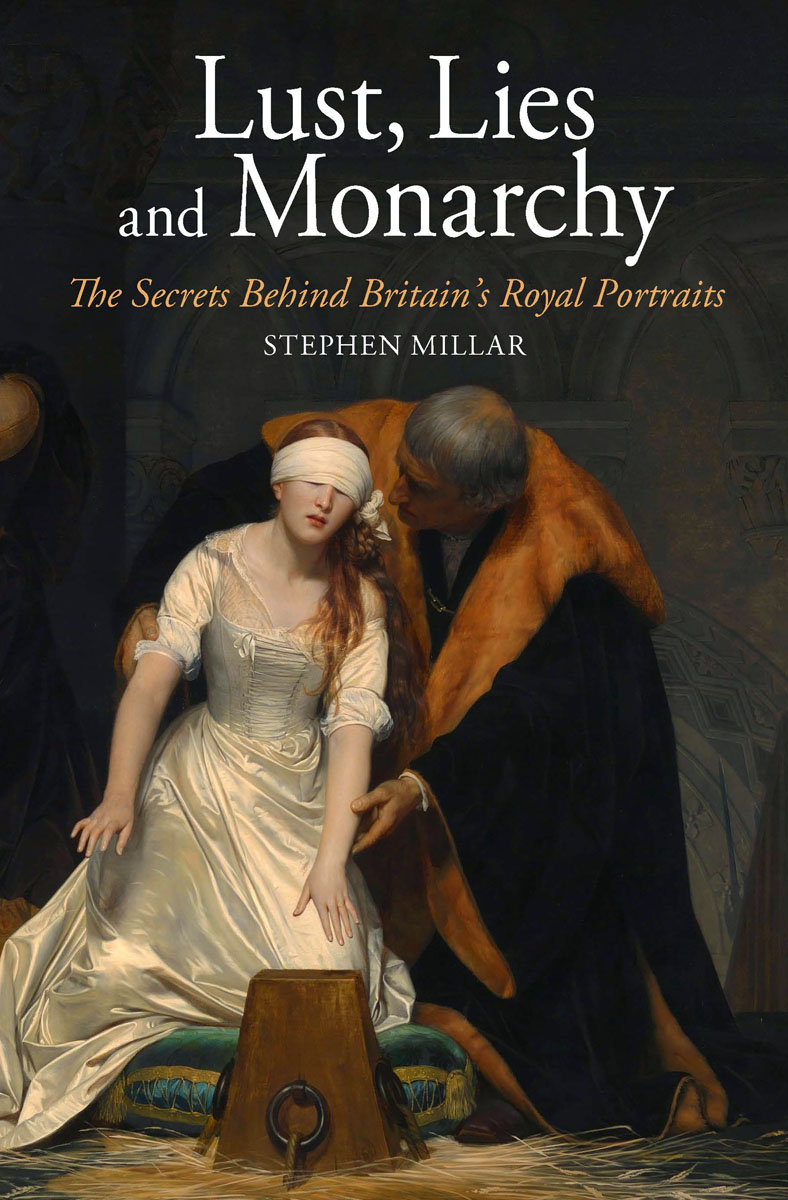

Title: Lust, lies and monarchy : the secrets behind Britains royal portraits /Stephen Millar.

Description: New York : Museyon, [2020] | Includes index.

Identifiers: ISBN: 9781940842288 | LCCN: 2019953309

Subjects: LCSH: Great Britain--Kings and rulers--Portraits. | Great Britain--Kings and rulers--Biography. | Queens--Great Britain--Portraits. | Queens--Great Britain--Biography. | England--Kings and rulers--Portraits. | England--Kings and rulers--Biography. | London (England)--Guidebooks. | BISAC: HISTORY / Europe / Great Britain / General. | ART / Subjects & Themes / Portraits.

Classification: LCC: DA28.1 .M55 2020 | DDC: 941.0099--dc23

Published in the United States and Canada by:

Museyon Inc.

333 East 45th Street

New York, NY 10017

Museyon is a registered trademark.

Visit us online at www.museyon.com

ISBN 978-1-940842-28-8

ISBN 978-1-940842-29-5 (e-Pub)

ISBN 978-1-940842-30-1 (e-PDF)

ISBN 978-1-940842-31-8 (Mobi)

To my childrenPatrick, Anna, Blythe and Arran

Lust, Lies and Monarchy

The Secrets Behind Britains Royal Portraits

INTRODUCTION

he British royal family can trace its origins back over 1,200 years, making it one of the most enduring ruling dynasties in the world. The fact that it has survived into the 21st century is testament to the familys ability to adapt to the religious, social, political and scientific revolutions that have impacted civilisation. Other European houses were swept away by these forces, but the British royal family has managed to change course, often just in time, to avoid being consigned to the history books.

he British royal family can trace its origins back over 1,200 years, making it one of the most enduring ruling dynasties in the world. The fact that it has survived into the 21st century is testament to the familys ability to adapt to the religious, social, political and scientific revolutions that have impacted civilisation. Other European houses were swept away by these forces, but the British royal family has managed to change course, often just in time, to avoid being consigned to the history books.

The role of art in the monarchys story is a small yet important one. In the modern age, it is hard to fathom that for many centuries most ordinary people would never see their sovereign in the flesh or have any idea of what he or she looked like. This lack of visual connection meant the monarchy was viewed as a distant institution, inevitable rather than celebrated.

The Renaissance and the invention of the printing press changed everything. Books and pamphlets were printed on a new scale, resulting in the spread of ideas that challenged the status quo. A concurrent revolution in the cultural sphere saw the emergence of great artists who began to achieve fame beyond their own localities.

It was at this moment of huge change in Europe that the Tudor dynasty claimed power in England, beginning with Henry VII. At this time England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales were seen by most people in mainland Europe as cultural and political backwaters, almost barbaric compared to the great kingdoms of Spain, Italy and France. However, the Tudors, conscious that many regarded them as usurpers, were determined to establish their brand.

Art helped them do this.

Henry VIII, the archetypal Renaissance prince, had a deeply troubled reign. Having split with Rome over his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, he had enemies on all sides. To project the image of a strong, capable ruler, he employed the services of Hans Holbein the Younger, possibly the finest artist then working in Europe. The investment paid dividends.

Holbeins depiction of Henry in the Whitehall mural was said to overwhelm viewers, and it was copied and distributed widely. It remains to this day the defining portrait of Henry, the image most people think of when they think of the king. It also exemplified the nature of royal propaganda. To Henrys enemies, it projected the image of a strong king not to be messed with, to his subjects a ruler who would look after them. But it was not the real Henry, who was cursed by failing health, declining mental powers and open sores on his legs that refused to heal. Royal propaganda was about creating an impression, not reality. It was about lies, not truth.

Art was also important for diplomatic purposes. Holbein famously travelled Europe painting portraits of eligible young women for his master Henry to marry.

Elizabeth I continued her fathers investment in art as a political tool. Hundreds of portraits of her were made during her reign, and most were subject to rigid rules about how she should be shown. This explains why she looks to be no older than in her thirties when she was painted near the end of her long life. Portraits of Elizabeth, particularly as it became clear she would not produce an heir, were designed to show her as a deitythe Virgin Queenwho could survive any obstacle, even multiple assassination attempts.

It was only in the 17th century that the royal family began to invest in art for arts sake. Prince Henry Stuart and his younger brother Charles I were the first serious art collectors in the royal family. Charles invested huge sums in buying art by the great masters, driving up prices. Whilst Charles genuinely appreciated art, his acquisitions also were a statement to other dynasties in Europe that the British royals were their cultural equals and were willing to spend what it took to catch up.

Charles I not only bought great paintings by dead painters, he invested in contemporary talents. His patronage of the Flemish painter Anthony Van Dyck made the standard of British royal portraiture the equal of anywhere else. Charles also commissioned busts by Bernini, and he enlisted Rubens to paint the ceiling of Banqueting House.

But Charles I had a major flaw: He was unable to read the way society was changing around him and consequently to adapt in order to survive. Convinced his power was God-given, he took on Parliament and the growing democratic institutions and lostboth the Civil War of the 1640s and then his head on a chopping block in Whitehall in 1649. His enormous art collection was sold off, and for a few years it seemed the royal family was extinct.

However, whilst many disliked the royals, many also were scared of the chaos and anarchy produced by the power vacuum that followed the death of the Parliamentary champion Oliver Cromwell. Charles II was therefore invited back to take his fathers throne in 1660. He was a canny ruler who concentrated on enjoying life rather than taking on Parliament. This endeared him to an exhausted country. But the king was also careful to commission works of art that re-established the grandeur of the monarchy. He also vigorously pursued the return of his fathers art collection that had been sold off.

The public became fascinated with the goings-on at court. Charles had thirteen mistresses and multiple illegitimate children. The Dutch artist Peter Lely witnessed the scandalous life of the Restoration court at first hand, and the king sat for him many times. Lely also captured the licentious mood of the court when he was commissioned to paint the most beautiful women of its inner circle, many of whom had been mistresses of Charles and his brother. The series, known today as the Windsor Beauties, originally hung in the rooms of Charles brother James, later James II. This was not art as royal propaganda, but a celebration of the fun-loving age, capturing the pinups of the late-17th century.

Next page

he British royal family can trace its origins back over 1,200 years, making it one of the most enduring ruling dynasties in the world. The fact that it has survived into the 21st century is testament to the familys ability to adapt to the religious, social, political and scientific revolutions that have impacted civilisation. Other European houses were swept away by these forces, but the British royal family has managed to change course, often just in time, to avoid being consigned to the history books.

he British royal family can trace its origins back over 1,200 years, making it one of the most enduring ruling dynasties in the world. The fact that it has survived into the 21st century is testament to the familys ability to adapt to the religious, social, political and scientific revolutions that have impacted civilisation. Other European houses were swept away by these forces, but the British royal family has managed to change course, often just in time, to avoid being consigned to the history books.