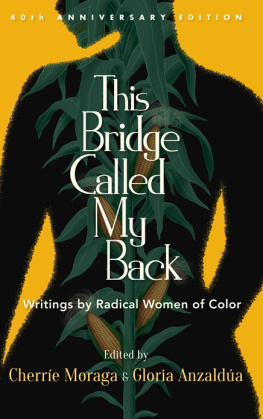

Some peoples names in this memoir were changed or were replaced with generic identifiers.

The Spanish in this work emerged when the writing naturally evoked it. Not that much, but enough, I hope, for the reader to experience this writing as a MexicanAmerican work.

C.M.

E lvira Isabel Moraga was not the stuff of literature. Few bemoan the memory loss of the unlettered. My motherand her generation of MexicanAmerican womenwas to disappear quietly, unmarked by the letter of memory, the memory of letter. But when our storytellers go, taking their unrecorded memory with them, we their descendants go too, I fear.

Maybe its about turning sixty. Maybe at such a substantive age, one can finally weave together enough of the threads of ones life to interpret a design from them. For my part, I hold one thickly braided cord as storymy queer self and my writer self, and each would bring me home to my Mexicanism. And my Mexicanism would bring me home to an earlier Amrica; to the Indian memory of bay leaf and madrone, desert chaparral, the Pacific always an ocean breeze away. It would also bring home to me a culture of memory and prophesythe harbinger of loss upon the horizon.

As a U.S. inheritor of Mexican ancestry, I have walked the reddening road of an Occupied America that anoints membership only to those born north of the watery divide of el Ro Grande. A border of river as thirsty as the desert into which it bleeds, leaving my relatives to drown in its grit. Growing up, my elders, well-meaning, told my generationGo that way, hijos. Look north to your future. They asked us to betray them, to forget them.

Walk that way, mija.

They didnt know the cost.

How to explain the complexity of this? What it means to benot just me but us. To know yourself as a member of a pueblo on the edge of a kind of extinction, and at the same time a lesbian lover and mother, where you truly do live your life in constant navigation through whatever part of your identity is being snuffed out that morningin the classroom, at the community meeting, the gasoline station, the take-out counterMexican, mixed-blood, queer, female, almost-Indian. And a poverty masked by circumstance.

For all my feminism, this is why I left a white womens movement in the late 1970s. So I wouldnt have to explain anymore, translate anymore. Because translating, I knew, would keep me from the harder work of going home: of trying to figure out, within the context of my ethnicity and culture, what Mexican & American / Indian & Catholic / rape & racism had to do with sexual desire and a contrary gender. And, just maybe, my return as a writer would matter to my pueblo. Maybe, in some small way, my visible queernesswhich I knew was representative of so many otherscould help make us a more resilient people.

Perhaps my writing has never really been about me. Perhaps it was about she all along: she without letters; she fallen off the map of recorded histories; she that is my history and my future with every mexicana female worker who comes to, or is born into, these lands of an ill-manifested destiny. She, the first and last point of my return.

There was no library in our home growing up. I did not sneak to read beneath the secrecy of flashlights under blankets. My reading stumbled out loud and my handwriting fell thick and crooked on wide-ruled paper. But I knew to listen. I listened to Elviras stories, to my tas stories, to my sisters promptings, Remember this moment, hermanita. I made mental records of their words, of being read to at night by that same sister who believed in romance, something that came on a horse and swept a woman up, not so unlike Elviras dreams.

I had only one romancethe love of an intractable Elvira, and this is what would shape my lesbianism and this is what would mark my road as a Mexican and this is what would require me to remember before and beyond my mother. I am a woman who knew myself daughter and son at oncea protector and provider for women and children. I have learned to confront police and rapists and silent enemies from within and have lived to tell of it.

I had never fully grasped the early years of my mothers life until I slowed down long enough to silently witness her last ones. In her final handful of years, the full distance of a near-century lifetime would flash back in a second of recall, never to reappear. And yet my mothers failing mind once and forever convinced me of the bodys ability to hold memory, which long surpassed her ability to speak it. It seems that when the body goes, memory resides in the molecules about us. We breathe in the last exhale of our mothers breath. This is what they bequeath to us. As they also bequeath their stories.

Elviras is the story of our forgotten, the landscape of loss paved over by American dreams come true. And maybe thats the worst of it (or what I fear)that our dreams can come true in America, but at the cost of a profound senility of spirit. If we forget ourselves, who will be left to remember us?

And so I followed the trail of my mothers fleeting reminiscences, picking up in the wake of her steps each and every discarded scrap of unwritten testimonio. This is what the spiritual country of my mothers departure asked of me, in the unspoken world of the deeply human.

My mother, in her little black sweater with the faux fur collar and fake string of pearls, is celebrating her ninetieth birthday. Seeing her made-up like this, even amid the obligatory pleasantly pastel decor of twenty-first-century eldercare suburbia, I catch a momentary glimpse of Elviras past, she who appeared in the sepia-toned photographs of a late-1920s Golden Age Tijuana: Elvirita, linking arms with her girlfriends in front of the Foreign Club; sprawled beneath the bare arm of a fledgling city tree; hip to hip with her cuate, Esperanza, on the bumper of a Model A Ford. Elvira: in the calf-length shapely skirt, the matching white heels, and the low-slung blouse with its draping bow. The bright red lips that do not smile, but invite, as is appropriate for the era. Elvira had a grand life before her children ever came into it.

There were no fathers in the Moraga clan, not in those first Aztln turn-into-the-twenty-first-century generations. There were men, yes; men who came and left the household with a single mans prerogative and secrets; men who answered to no one, and never to a female.