Pagebreaks of the print version

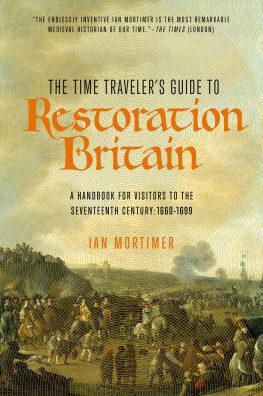

A HISTORY OF DEATH IN

17TH CENTURY ENGLAND

A HISTORY OF DEATH IN

17TH CENTURY ENGLAND

BEN NORMAN

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

PEN AND SWORD HISTORY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire - Philadelphia

Copyright Ben Norman, 2020

ISBN 978 1 52675 526 1

eISBN 978 1 52675 527 8

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52675 528 5

The right of Ben Norman to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Books Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing, Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Abbreviations

PCCRP | Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions |

Authors Note

Quotations from primary source material have retained their original spelling and grammar where applicable. To the best of the authors knowledge and ability dates within this book are in line with the Julian calendar, which was the calendar in use in seventeenth-century England and at the time was roughly 10 days behind the present-day Gregorian calendar. The Gregorian calendar was adopted in England in 1752. All years (again to the best of the authors knowledge and ability) are presented as beginning on 1 January, although in the 1600s it was common to celebrate the New Year on 25 March.

Picture Acknowledgements

In the book

Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Wellcome Collection. CC BY

John Barker [Public domain]

Public Domain, from the British Librarys collections, 2013

Abraham Storck [Public domain]

Sylvanus Urban [Public domain]

Public Domain, from the British Librarys collections, 2013

tyburntree.wordpress.com [Public domain]

Ralph Gardiner [Public domain]

Wellcome Collection. CC BY

en:User:Raymond Palmer [Public domain]

Jan Luyken [Public domain]

Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Manchester Art Gallery [Public domain]

Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Attributed to Henri Beaubrun (1603-1677) [Public domain]

Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Susan Doran [Public domain]

Public Domain, from the British Librarys collections, 2013

Picture Acknowledgements

Public Domain, from the British Librarys collections, 2013

Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Authors private collection

Authors private collection

Authors private collection

Authors private collection

Authors private collection

Authors private collection

Authors private collection

Authors private collection

Jacob Truedson Demitz for Ristesson History [Public domain]

The Portable Antiquities Scheme/The Trustees of the British Museum [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-sa/2.0)]

On the cover

(Townspeople fleeing to the countryside to escape the plague in England, 1630. Hand-coloured woodcut.) North Wind Picture Archives / Alamy Stock Photo

(The beheading of Charles I outside the Banqueting Hall of Whitehall in 1649. Engraving with etching.) Wellcome Collection. CC BY

(Surgeons performing an operation on a womans breast in the seventeenth century.) Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Chapter headers

(Skull on a book) Public Domain, from the British Librarys collections, 2013

Acknowledgements and Dedications

I wish to thank Pen and Sword Books for giving me the incentive to follow through with this project and agreeing to publish the book, particularly as I am a first-time author. My particular thanks go to Aileen at P&S for answering the many questions I had throughout the process. More generally I would like to thank my family and friends (you know who you are) for their support and encouragement, and for assuring me that the topic sounded interesting. The proof of the pudding is in the reading.

Bearing in mind that this book is as much about life as it is death, I am keen to dedicate it to two individuals: Joy Bradford, who sadly departed this world three years ago now, and baby Alba-Rose, who as I type these words is not three weeks old and has her whole life ahead of her.

Ben Norman, August 2019

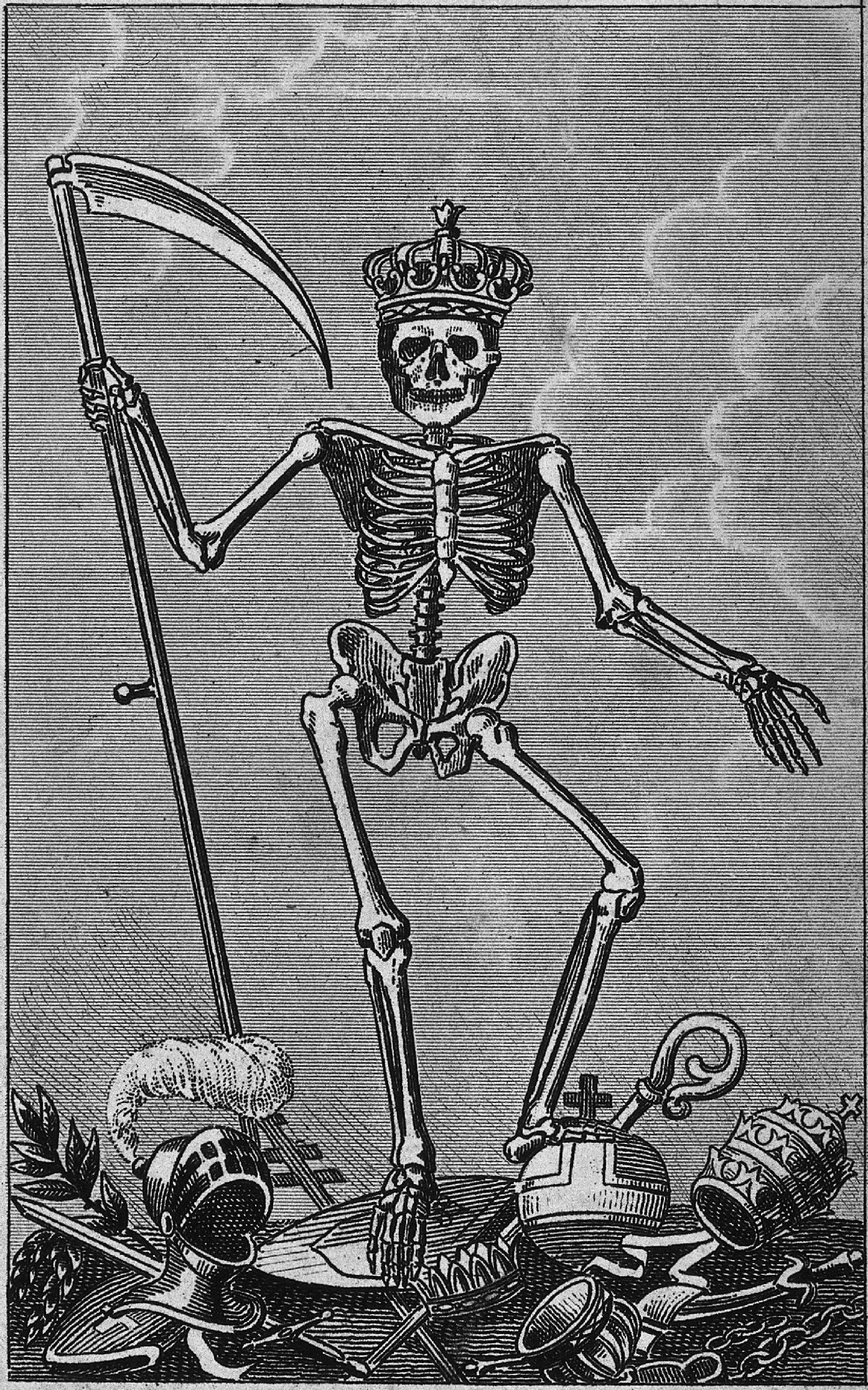

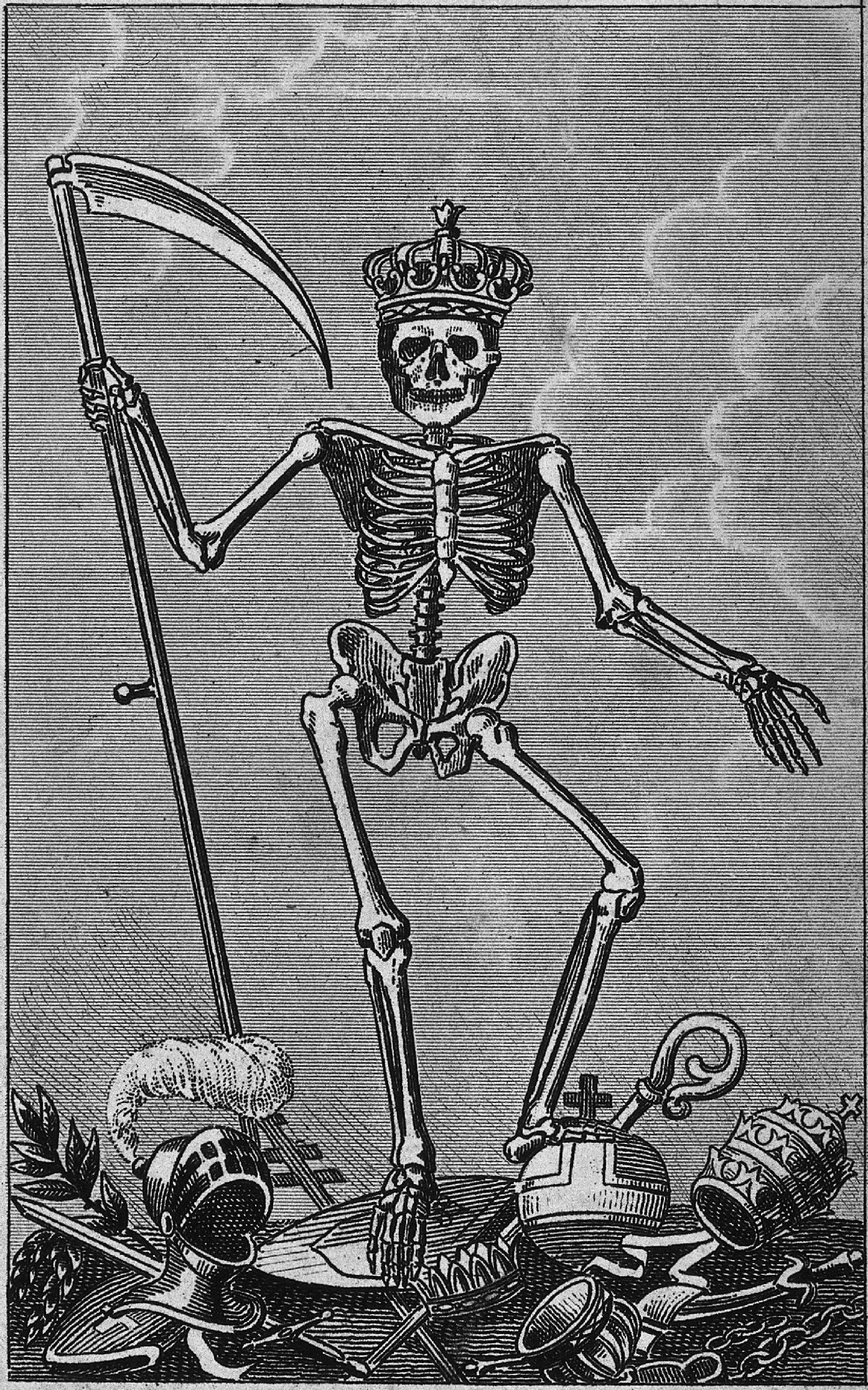

1. Death as king, by an unknown engraver.

Introduction

On entering his fiftieth year in 1673, Sir Edward Harley of Herefordshire noted:

O Lord! in thy hand is the breath of all mankind, and it is only God who holdeth our soul in life. But in most special manner I ought to praise my God, who preserved me from abortion at Burton-under-the-Hill. In this place, this day gave the light of life to poor clay, and for forty-nine years thou hast granted me life and favour, and thy visitation hath preserved my spirit. Lord, thou hast granted me life in the deliverances of life: when a child, from the chin-cough, measles, small-pox twice, and danger of drowning in the moat; when a man, from many perils in the wars, particularly when my horse was shot, when my arm was hurt, when a muskett-bullett, levelled at my heart, was bent flat against my armour, not reckoned of such proof, without any harm to myself. [] I have often been preserved in journeys and voyages from thieves; from waters, specially in a dangerous passage once at Newnham. Many times I crossed the sea between England and Flanders, allways safely [] I was delivered from the malitious accusation of the army, 1647, and my God made my speech in my defence in Parliament acceptable. That year I was preserved from the plague, of which my servant died, and at the same time recovered from a dangerous pestilential fever.

Harley recognised that he was lucky to be alive. He was of the opinion that many different things could have killed him in the long years between his birth and the present day. As an infant he had been in danger of succumbing to a succession of childhood diseases, including chincough (better known today as whooping cough), measles, and smallpox, the latter of which he had managed to catch twice. As a man he was no safer. Armed conflict brought its own risks, some too horrific to contemplate, and had endangered his life on several occasions. During the English Civil War, Harley was mercifully spared from a shot to the heart by a musket bullet only because it bounced off his armour. He acknowledged that it was something of a miracle that he had not been set upon and killed by thieves while on the road, as many others had been, or that he had survived numerous sea crossings when so many sailors had drowned. The Member of Parliament found it incredible that he had successfully avoided the plague, too, even though it had killed thousands of defenceless victims, including his own servant.