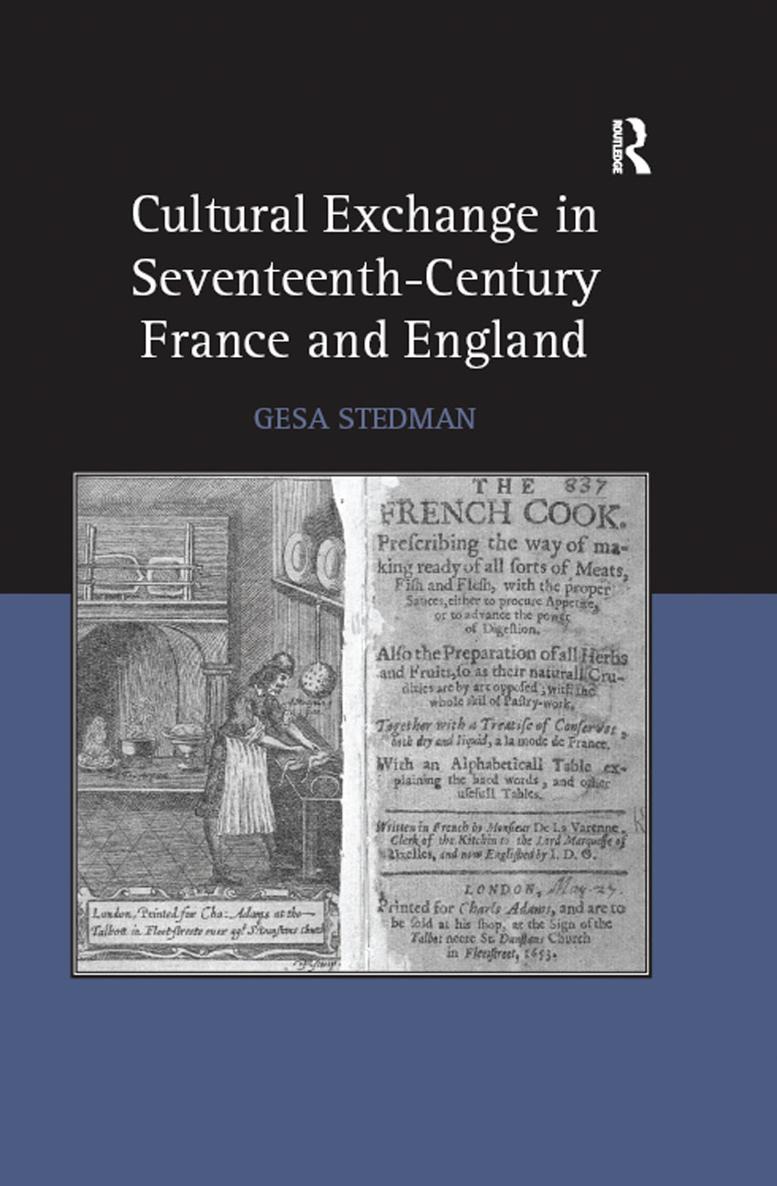

CULTURAL EXCHANGE IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE AND ENGLAND

The book is dedicated to Margarete Zimmermann and Jrgen Schlaeger, whose mentoring and mediating activities have been essential in more ways than one.

Cultural Exchange in Seventeenth-Century France and England

GESA STEDMAN

Humboldt University of Berlin, Germany

First published 2013 by Ashgate publishing

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright Gesa Stedman 2013

Gesa Stedman has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Stedman, Gesa.

Cultural exchange in seventeenth-century France and England.

1. England Civilization 17th century. 2. England Civilization French influences 3. France Civilization 17th century. 4. France Civilization British influences

I. Title

303.48241044-dc23

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stedman, Gesa.

Cultural exchange in seventeenth-century France and England / by Gesa Stedman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7546-6938-8 (hardcover: alk. paper)

1. FranceRelationsEngland. 2. EnglandRelationsFrance. 3. Cultural fusion FranceHistory17th century. 4. Cultural fusionEnglandHistory17th century. 5. FranceIntellectual life17th century. 6. EnglandIntellectual life17th century. 7. FranceSocial life and customs17th century. 8. EnglandSocial life and customs 17th century. 9. FranceForeign public opinion, British. 10. EnglandForeign public opinion, French. 11. Cultural relationsHistory17th century. I. Title.

DC59.8.G7.S74 2012

303.4824104409032dc23

2012022046

ISBN 13: 978-0-7546-6938-8 (hbk)

Contents

4.4 Englands Vanity, engraving by T. Carlett (?), illustration from anonymous, (1683). (British Library)

4.5 Title page of The Second Part of Vox Populi; or Gondomar appearing in the likenes of Matchiavell in a Spanish Parliament, portrait of Count Diego Gondomar (1630s). (National Portrait Gallery)

4.6 Social Types of Foreigners

4.7 The Comical Revenge, or Love in a Tub, frontispiece from George Etherege (1725; 1664). (British Library)

4.8 Metaphoric Effects

During the early modern period, the so-called Old Style or Julian calendar was in use in England. Consequently, England was 10 days behind the Continent which, for the most part, had adopted the New Style or Gregorian calendar from 1582 onwards. Therefore, 1 May in England would be 11 May everywhere else in Western Europe.

In order to prevent confusion, I have given dates relating to countries which had adopted the new reckoning, for example France, in both styles: 1/11 May. The first date refers to the Old Style calendar, the second to the New Style one.

Although for legal purposes the new year in England began with 25 March (Lady Day), I have followed Samuel Pepys and general custom which stipulates that the year begins on 1 January. Although Pepys and some other sources give overlapping year dates for the period between 1 January and 24 March for instance 1 March 1660/1661, I have consistently used a single year date 1 March 1661 following the New Style calendar.

Many people have supported me in the course of writing this book. I am grateful to the following people for their help, sometimes great, sometimes small:

To Margarete Zimmermann, for her continued interest in the topic and my rendering of it.

To Jrgen Schlaeger, for turning a sprawling manuscript into a readable book.

To Jana Gohrisch, for being a careful reader and a detailed critic.

To Ansgar Nnning, for encouraging me to finish the book, and for suggesting I might find cognitive metaphor theory useful.

To Christiane Eisenberg, for introducing me to cultural exchange studies.

To Ashgates reader, for her/his helpful suggestions.

To Whitney Feininger and all the team at Ashgate who make producing a book a pleasure, rather than a chore.

To Corinna Radke who was responsible for turning the manuscript into a book.

To the members of the work in progress colloquium at the Freie Universitt and the Humboldt-Universitt zu Berlin, in particular to Manfred Pfister and Andrew Johnston, for two very good ideas concerning the textual responses to cultural exchange, and to the medieval and early-modern practice of marriage by proxy.

To the members of the German Historical Institute, London, for showing me what historians are interested in and what they find irrelevant.

To Tobias Brandenberger, Dorothea Nolde, and Claudia Opitz for sharing their thoughts on early-modern cultural exchange with me and inviting me to their conferences.

To the members of the research colloquium of the Centre for French Studies, Freie Universitt Berlin, for their questions and comments on an earlier version of parts of the book.

To the staff at the British Library, London, the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and the Bibliothque Nationale, Paris, for help with obscure manuscripts, titles, and books.

To the British Library, the British Museum, the Royal Collection, the National Portrait Gallery, the National Gallery of Art (Washington D.C.), and Chatsworth Photo Library for providing me with copies of paintings, engravings, and images.

To the student assistants at both Justus-Liebig-Universitt Giessen and the Centre for British Studies, Humboldt-Universitt zu Berlin, for help with the bibliography, the footnotes, and obtaining books.

Special thanks to Christina Rcker for help with the formatting and to Sebastian Thalheim for finding the pictures and illustrations.

To the librarian of the Centre for British Studies, Evelyn Thalheim, for obtaining books for me at short notice and taking an interest in my research.

My parents Monika Stedman and Michael Stedman have been both careful readers and patient listeners. Their continued support in many areas has allowed me to focus on my work in a way otherwise impossible. Nils Kummert and Liam and Lynn Stedman have an unfailing belief in my abilities, and make it all worthwhile.

Thank you to all of you.

Gesa Stedman, December 2012

Introduction:

Theories of Cultural Exchange

But his [Charles IIs] fair soul, transformd by that French dame,

Had lost all sense of honor, justice, fame.

Like a tame spinster inth seragl he sits,

Besiegd by whores, buffoons, and bastard chits;

Lulld in security, rolling in lust,