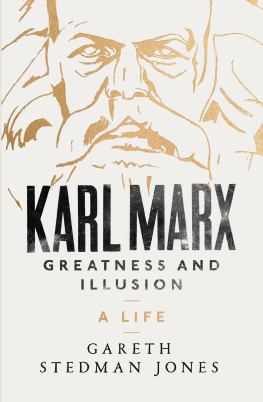

AN END TO POVERTY?

GARETH STEDMAN JONES

AN END TO POVERTY

A HISTORICAL DEBATE

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright Gareth Stedman Jones, 2004

First published by Profile Books Ltd, London

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-51079-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A complete CIP record is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 0231137826 (cloth : alk. paper)

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

To my mother

CONTENTS

This book has been written to accompany the Anglo-American Conference of the Institute of Historical Research, whose theme in 2004 was Wealth and Poverty. I wish to thank the Director of the Institute, David Bates, for encouraging me to undertake this assignment. I would also like to thank Peter Carson, Penny Daniel, Maggie Hanbury, Sally Holloway and Tim Penton for the part they have played in the publication of this book.

The thinking which shaped it is to a large extent the result of discussions and seminars which have taken place at the Centre for History and Economics at Kings College, Cambridge since 1992. I wish to thank the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation which has so generously supported the activities of the Centre. I have learnt from many who have participated in the intellectual life of the Centre, but especially from Emma Rothschild who provided constant inspiration and encouragement, while I was writing this book. Those who have helped to manage the Centre have also been of invaluable assistance, in particular Inga Huld Markan, Jo Maybin, Rachel Coffey and Justine Crump.

There are many others who have provided important suggestions, insights or help as this book was being prepared. I would particularly like to mention Robert Tombs, Daniel Pick, Tristram Hunt, Michael Sonenscher, Istvan Hont, David Feldman, Barry Supple, Sally Alexander and Daniel Stedman Jones. Finally, a special thanks to Miri Rubin who persuaded me that it was possible to write this book and did so much to help it towards its completion.

This book employs history to illuminate questions of policy and politics which still have resonance now. It aims to make visible some of the threads by which the past is connected with the present. It does so by bringing to light the first debates, which occurred in the late eighteenth century, about the possibility of a world without poverty. These arguments were no longer about Utopia in an age-old sense. They were inspired by a new question: whether scientific and economic progress could abolish poverty, as traditionally understood. Some of the difficulties encountered were eerily familiar. Many of the problems which politicians and journalists imagine to have arisen in the world only recently globalisation, financial regulation, downsizing and commercial volatility were already in the eighteenth century objects of recurrent concern.

It is of course true that the world in which discussion of these issues first arose was very different from our own. It was dominated by the revolutions of 1776 in America and 1789 in France, as well as by the first movements to overcome slavery and empire. The arguments discussed in this book took place in a period which witnessed the overturning of ancient forms of sovereignty across Europe, direct assaults upon monarchy, aristocracy and church, crises of religious belief, the emergence of the common people as an independent political force, and a war fought across all the oceans of the world.

But to a greater degree than we are prone to imagine, those upheavals and their legacy are still relevant to us. Our conceptions of the economy, both national and international, and its relationship to political processes are still in some ways shaped by the conflicts discussed in this book. So are the relationships between religion, citizenship and economic life. Those who doubt the relevance of history because they believe that the world was made anew by the defeat of Communism, the end of the Cold War, and the demise of socialism at the beginning of the 1990s, do not escape its hold. They simply become the guileless consumers of its most simple-minded reconstructions. Those who devised the new reform programmes of post-socialist parties, desperate to remove any residue of an old-fashioned and discredited collectivism, hastened to embrace a deregulated economy hopefully moralised by periodic homilies about communitarian sentiment. By doing this, they imagined themselves to be buying into an unimpeachable and up-to-date liberal tradition handed down in a distinguished lineage of economists and philosophers inspired by the laisser faire libertarianism of Adam Smiths The Wealth of Nations.

This book reveals that such assumptions are at best dubious and, for the most part, false. The free market individualism of American conservatives and the moral authoritarianism which often accompanies it are not the products of Smith (although they certainly draw selectively upon certain of his formulations), but of the recasting of political economy in the light of the frightened reaction to the republican radicalism of the French Revolution.

Smiths analyses of moral sentiments and commercial society were not the exclusive possession of any one political tendency. The battle to appropriate his mantle was closely intertwined with the battle over the French Revolution itself. Modern commentators are agreed that Smith was not in any distinctive or meaningful sense a Christian, while those who wrote about him at the time strongly suspected it; worse still, at least for contemporaries, the evidence provided by his revisions to the 1790 edition of The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which he had originally written in 1759, suggested that at the end of his life he was even less of a Christian than before. This was not merely a minor or incidental quirk in Smiths picture of the world, it informed his fundamental conception of human motivation as well as his theory of history. In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith wrote of the ambition which drove on the poor mans son to strive to become rich and, if successful, to advertise his newfound status by procuring mere trinkets of frivolous utility. After a disquisition on the impossibility of translating wealth into happiness, Smith concluded:

Power and riches appear then to be, what they are, enormous and operous machines contrived to produce a few trifling conveniences to the body, consisting of springs the most nice and delicate, which must be kept in order with the most anxious attention, and which in spite of all our care are ready every moment to burst into pieces, and crush in their ruins their unfortunate possessor.

Nevertheless, he continued, It is well that nature imposes on us in this manner. It is this deception which rouses and keeps in continual motion the industry of mankind.

The idea that some kind of trick or self-deception was the basic motivating factor behind human activity, but that it was nevertheless to be cherished because it explained why mankind was induced to found cities and commonwealths, and to invent and improve all the sciences and arts, which ennoble and embellish human life was difficult to integrate either into Christianity or into what in the years after 1789 was presented as a post-Christian republican alternative. Smiths picture derived from classical sources, part stoic and part epicurean. It sat ill with Christian evangelicalism. Nor did it accord well with counter- or post-revolutionary apologias for aristocracies, merchants, established churches, low wages or the outlawing of combinations of labourers. But then nor could it be said to endorse republicanism, egalitarianism, democratic representation or the toppling of aristocracies. Supporters and opponents of the Revolution, therefore, annexed different parts of Smiths picture of commercial society to support rival visions of social and political life.

Next page