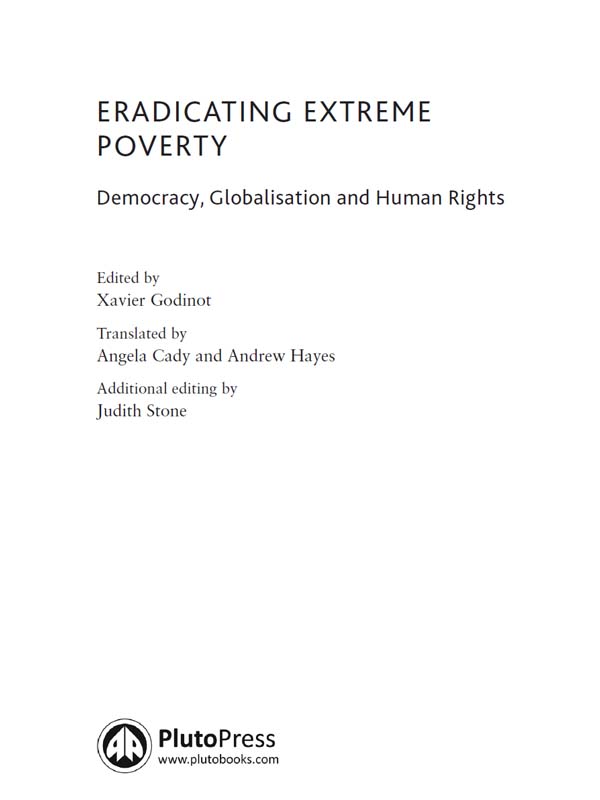

First published in French 2008 by Presses Universitaires de France

English edition first published 2012 by Pluto Press

345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA

www.plutobooks.com

Distributed in the United States of America exclusively by

Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martins Press LLC,

175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010

Copyright Xavier Godinot 2008; English translation 2012 ATD Fourth World

The right of the individual contributors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 3198 0 Hardback

ISBN 978 0 7453 3197 3 Paperback

ISBN 978 1 8496 4632 1 Epub

ISBN 978 1 8496 4633 8 Kindle

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Designed and produced for Pluto Press by Chase Publishing Services Ltd

Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England

Simultaneously printed digitally by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, UK and Edwards Bros in the United States of America

ATD Fourth World

The international movement ATD Fourth World is a non-governmental organisation with no religious or political affiliation which engages with individuals and institutions to find solutions to eradicate extreme poverty. Working in partnership with people in poverty, ATD Fourth Worlds human rights-based approach focuses on supporting families and individuals through its grassroots presence and involvement in disadvantaged communities, in both urban and rural areas, creating public awareness of extreme poverty and influencing policies to address it. It brings together people from all walks of life, starting with people living in the most extreme poverty and has a presence on the ground in 30 countries on five continents. Through its Permanent Forum on Extreme Poverty, an international network of anti-poverty organisations and human rights defenders, it maintains links with people and associations in 155 countries. Florianne Caravatta, Marilyn Ortega Gutierez, Alasdair Wallace, Patricia and Claude Heyberger, Rosario Macedo de Ugarte and Marco Aurelio Ugarte Ochoa, who authored this book, have been full-time volunteers in this movement for many years.

Trained in politics and economics for 40 years, Xavier Godinot, who coordinated the book, has combined academic and grassroots approaches in the fight against extreme poverty. He directed ATD Fourth Worlds research institute for twelve years. He then ran anti-poverty projects in Madagascar, with families living in rubbish dumps. He is now working at the headquarters of ATD Fourth World in France where he is coordinating an action research project in eight countries to evaluate the Millennium Development Goals.

Preface to the English Edition

Xavier Godinot

Three years have elapsed since the French version of this book was published by the Presses Universitaires de France. I spent most of this time in Antananarivo, the main town of Madagascar, as Regional Coordinator for the Indian Ocean region of the International Movement ATD Fourth World, a non-governmental organisation dedicated to combating extreme poverty and exclusion in both the northern and southern hemispheres through partnerships with people in extreme poverty. It was an outstanding position from which to expand my knowledge of what it means to live in extreme poverty, and how to fight against it in different contexts. This preface reflects a lot of what I learnt in these three years.

In Antananarivo, my wife and I did not stay in any of the wealthy and gated communities used by mostly white foreigners. For three years, we rented a flat in a working-class neighbourhood, close to the shanty town of Antohomadinika, at the north-west limit of the capital. With French and English colleagues from the same NGO, we were the only white inhabitants in the area. We were lucky enough to have electricity, cold water and toilets in our flat, which was a luxury in a town where 75 per cent of the inhabitants have none of these facilities. We learned a lot from some inhabitants of Antohomadinika and Andramiarana, who had worked closely with our predecessors for years. Eventually, we delivered a collective report to the World Bank on The Urban Challenge in Madagascar: When Destitution Wipes Out Poverty. It was presented to a large and diverse audience, including families in extreme poverty, in October 2010, on the occasion of the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty, providing these families with a platform to voice their daily struggles and concerns.

The shantytown of Antohomadinika III G Hangar is a maze of shacks and alleys inaccessible to cars and invisible from the main road. It comprises more than 9,000 inhabitants, of whom 70 per cent are under 18 years old. Its population has increased by more than 50 per cent in 14 years. An additional estimated 10 per cent, who did not register at the city council mainly because of their poverty, should be added to this count. Most people survive on precarious and informal work, and most of the households, comprising on average six people, live in wooden shacks of between four and eight square metres with dirt floors, built on land that is flooded during the rainy season. Within their shacks, they may paddle in water for weeks. During a meeting in the area in January 2010, convened for the preparation of our report to the World Bank, a group of inhabitants shared their concerns, including Mrs Mamy who said When it rains, dirty water flows into the houses. Then, we put the beds up on bricks. Most families rent their shacks and struggle to pay the landlord, leading to the constant risk of eviction. As only five public water taps are available, people have to queue for hours to bring home the buckets of water they need for the day. Personally, I go to the tap at 4.30 a.m. to get water, and I come back at 5.50, said Mrs Hanitra. The sanitation and waste collection are very poor: only two garbage skips and three toilet blocks, which residents must pay to use. As this area has the highest prevalence of severe food insecurity and monetary poverty in Antananarivo, few people use the toilets.

The living conditions on the garbage dump of Andramiarana, ten kilometres north of the capital, are worse still. More than 650 people stay here, making a living as waste pickers. Among them, 63 per cent are under 20 years old. Most households are homeless families who have been evicted from place to place for years, eventually ending up at the dump. All of them strive to survive in dire straits. The poorest live in shacks made of plastic bags and wood, that one can enter only on all fours. Before starting a cash transfer programme funded by UNICEF, we found out that 70 per cent of them were not registered at the city council, which means that they had no legal existence, no citizen rights, and that their children could not enrol in school. Mrs Hanta, a single mother of four living on the dump, told us in July 2009: The biggest injustice we suffer is ignorance. Here, people had no schooling and are abused, since they dare not confront those who are educated. We dare not and cannot voice our ideas to those who are educated. This is why we get only precarious and low paid jobs, that comply with no legal standard.