First published 1994 by Westview Press

Published 2019 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1994 by Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Timmer, Doug A.

Paths to homelessness: extreme poverty and the urban housing

crisis / Doug A. Timmer, D. Stanley Eitzen, and Kathryn D. Talley.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8133-0782-1 ISBN 0-8133-0783-X (pbk.)

1. HomelessnessUnited StatesCase studies. 2. PovertyUnited

StatesCase studies. 3. Urban poorHousingUnited StatesCase

studies. 4. UnemployedUnited StatesCase studies. I. Eitzen,

D. Stanley. II. Talley, Kathryn D. III. Title.

HV4505.T56 1994

362.5'0972dc20 94-15668

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-28237-0 (hbk)

This research was assisted in part by a Dana Foundation Faculty Development Fellowship Grant from the University of Tampa and a Lilly Foundation Development Grant from North Central College, Illinois.

We want to thank the people who shared their lives with us. We have learned much from them and want to give something back. Therefore, the royalties received from this book will be given to not-for-profit community groups in the struggle for low-income and affordable housing in Tampa and Chicago.

Doug A. Timmer

D. Stanley Eitzen

Kathryn D. Talley

I am eating outside of a ribs joint early on a Sunday evening in late July, at the corner of 53rd and Dorchester on the South Side of Chicago. A young black manmaybe in his mid-to-late twentiescomes up to my table.

"It's a tiresome world, isn't it? I've been livin' in my van for the last two months. Got my last check [unemployment] and there still ain't no work. I'm goin' to get out of here to Boulder or Wisconsin. My buddy wants to go to Colorado but I just want to go up to Wisconsin. You can find the same things there as you can in Colorado. We're gonna try to find a cave. I'm tired of this big-city, big-city prices. You get a cave and you ain't got to pay no rent. Ain't nobody can take it from you."

Before I can say much, he's on his way, leaving as quietly and quickly as he appeared.

"Take care, man," he says.

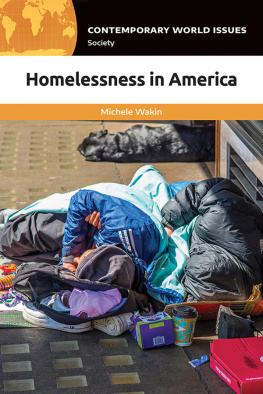

Understanding Homelessness: Industrial and Urban Decline

The homeless are the most visible of America's social problems. Homeless people are found everywhere: in cities, small towns, suburbs, and rural areas. They are on the evening news, especially when it is very cold and during the winter holidays. We see them huddled in frigid temperatures on steam grates. We encounter them as they beg for handouts along the sidewalks in front of the trendiest stores as well as in the alleys of the most run-down neighborhoods. We cannot escape them as they seek refuge in church doorways, subway terminals, libraries, parks, and stores. They are everywhere and their numbers are increasing.

The homeless are the poorest of the poor. Like other poor people, the homeless receive inadequate or no medical care, tend to be malnourished, experience discrimination, and are the objects of scorn and condescension by those more advantaged. But the poverty of the homeless is extreme. They are homeless because their economic resources are exhausted. They have no personal safety net and they have escaped the one supposedly supplied by society. Finding food and shelter are troubles every day. And, most notably, the homeless are much more visible than other poor people. Whether they sleep in the streets or in shelters, they are quickly and easily identified as social pariahs.

Homelessness is not just a matter of social class. Race is also a crucial determinant, since people of color are disproportionately among the very poor. For example, in 1991, 11.3 percent of whites were below the poverty line compared to 28.7 percent of Latinos and 32.7 percent of African Americans. If we look at those at half the poverty rate or lower, 3.9 percent of whites were in this extreme category of poverty compared to 9.9 percent of Latinos and 15.8 percent of African Americans (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1992:17-19). Within these impersonal statistics are institutional racism, which disadvantages racial minorities through residential segregation patterns, job discrimination, and inferior education, and the personal tragedies and indignities resulting from discrimination that disadvantages people of color.

Although homelessness is found throughout American society, it is particularly an urban phenomenon. Homelessness is especially urban because the cities are the endpoint of industrial and urban decline. The government's data for 1991 show that 43 percent of the nation's poor were found inside central cities (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1992:1). Homelessness in the United States is predominantly a problem of the inner cities because the poor there are especially vulnerable to the structural forces that lead to unemployment, layoffs, and plant closings. The poor in the inner cities are also relatively defenseless against the problems endemic to poverty because the cities are generally financially unable to provide a sufficient safety net to meet their needs. Finally, the poor in the cities find special difficulty in finding affordable housing because of high costs and ever fewer available units. This lack of housing supply for the poor is the primary reason, as we will document throughout this book, for the rapid rise in the homeless population in U.S. cities since the middle 1970s.

How are we to understand the phenomenon of homelessness? The most commonly used explanation focuses on the faults of those individuals who are homeless. This type of explanation is based on the ideology that opportunities for economic advancement are readily available for those willing to try. In this view, individuals are personally responsible for their successes or failures. Thus, homeless persons are to blame for their deprivation because of their drinking habits, their immorality, their mental instability, their illiteracy, or their lack of purpose and initiative. In other words, the homeless are homeless because they are drunk, unstable, or lazy. The problem with this approach is that it blames the victim and ignores the powerful structural forces that push many people into difficult situations beyond their control.

If the individualistic approach is correct, then the proportion of homeless should be about the same in all large cities of the world. Personal irresponsibility certainly occurs everywhere. If that is the reason for homelessness then there should be about the same proportion of homeless in Tampa as in Toronto or in Chicago as compared to Copenhagen. Since this is not the case, socioeconomic factors must account for the differences. Elliot Liebow argues (and we agree) that "the only things that separate people who have a home from those who do not are money and social support: Homeless people are homeless because they cannot afford a home, and their friends and family can't, or won't, help them out. I don't want to overlook the differences among us but I don't think they're as important as the samenesses in us" (quoted in Coughlin 1993:A8).