Homelessness Is a

Housing Problem

The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Anne G. Lipow Endowment Fund in Social Justice and Human Rights.

Homelessness Is a Housing Problem

How Structural Factors Explain U.S. Patterns

Gregg Colburn and Clayton Page Aldern

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

University of California Press

Oakland, California

2022 by Gregg Colburn and Clayton Aldern

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Colburn, Gregg, 1972- author. | Aldern, Clayton Page, 1990 author.

Title: Homelessness is a housing problem : how structural factors explain U.S. patterns / Gregg Colburn and Clayton Page Aldern.

Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021037026 (print) | LCCN 2021037027 (ebook) | ISBN 9780520383760 (cloth) | ISBN 9780520383784 (paperback) | ISBN 9780520383791 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: HomelessnessUnited States. | Metropolitan areasHousingSocial aspectsUnited States. | HomelessnessGovernment policyUnited States. | Homeless personsSubstance useUnited States.

Classification: LCC HV4505 .C6 56 2022 (print) | LCC HV 4505 (ebook) | DDC 362.5/920973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021037026

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021037027

Manufactured in the United States of America

31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To anyone who lives without stable housingand to the policy makers, organizers, advocates, researchers, practitioners, and those with lived experience working to end homelessness

Contents

Figures and Tables

FIGURES

TABLES

Acknowledgments

The motivation for this book stemmed from Greggs observation that the roots of the homelessness crisis in many cities in the United States were being misdiagnosed, often to frustrating and harmful ends. A public focus on mental health and drugscertainly, important risk factors for homelessnessdominates narratives in our home in the Puget Sound region, thereby narrowing the policy conversation. In discussions with stakeholders throughout the region, it became apparent that an intense focus on behavioral health might be masking a more important root cause of this crisis: housing market conditions.

Gregg shared the early vision for this book in 2019 with colleagues throughout the Seattle region. One such conversation proved to be particularly valuable and changed the course of this book project. Rogers Weed, then board chair of Building Changes (a nonprofit focused on homelessness), introduced the two authors of this book. After a number of productive and engaging conversations, Clayton and Gregg decided to collaborate on this project. The two of us collaborated on the analysis, Gregg wrote the majority of the manuscript, and Clay applied his expertise in data visualization to the images found in this book. In a sure sign of a productive partnership, this final product is far better than any that would have resulted from a solitary effort.

Gregg is grateful to the many people who provided insight, wisdom, and support throughout this process. At the University of Washington, a wonderful community of scholars, including Arthur Acolin, Scott Allard, Kyle Crowder, Rachel Fyall, Rebecca Walter, and Thasa Way have supported my professional development and have provided valuable feedback at various stages of the writing process. In addition, scholars from around the country including Thomas Byrne, Brian McCabe, and Beth Shinn also provided feedback and guidance. Numerous members of the Seattle community served as sounding boards throughout the writing process; a special thank-you to Kollin Min who was a key supporter of this project. Finally, Gregg is also thankful for his wife, Jen, and children Grace and Grant for their patience and support. Much of this book was written as we quarantined together during the COVID-19 pandemic. I love you all and am grateful for the joy and laughter you bring to my life.

Clayton extends his deep gratitude to the advocates and researchers with and without the lived experience of homelessness who have worked to help him and others understand the structural roots of the crisis. To Jeff Rodgers, Tess Colby, Aras Jizan, Marc Dones, Anne Marie Edmunds, Valeri Knight, Sarah Appling, Claire Aylward Guilmette, Deborah LAmoureux, Gerrit Nyland, Caroline Belleci, Geoff Campion, Vishesh Jain, Aman Sanghera, Annie Pennucci, Matt Lemon, Pear Moraras, Abby Schachter, Stephanie Roe, Jesse Jorstad, and Stephanie Pattersonthank you for your insight into (and leadership in) this space, and thanks for all you continue to teach us. Thanks to Jason Schumacher and Neal Myrick at the Tableau Foundation for your deep investments in data visualization and data literacy in homelessness policy and housing stabilityand for letting Clay use your software for exploratory analysis and figure drafting. To Sara Curran, Tim Thomas, and Thasa Way at the University of Washington for the critical support via the Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology: Thank you. Gratitude to Whitney Henry-Lester for the late-night chats to these ends and to Lowell Wyse for the late-night chats to other ends. A near-impossible degree of gratitude to Anneka Olson, whose patience knows no bounds: Thank you for your keen editing brain, critical perspective, and warm presence. Henry the Cat and Maple the Cat also offered pivotal moral support.

The final chapter of this book incorporates the ideas of researchers, practitioners, and policy makers from around the country. We are grateful to those who shared their research and opinions about the strategies needed to end homelessness: Whitney Airgood-Obrycki, Thomas Byrne, Tess Colby, Dennis Culhane, Mary Cunningham, Conor Dougherty, Mark Ellerbrook, Katie Hong, Aras Jizan, Jill Khadduri, Margot Kushel, Kollin Min, Stephen Norman, Beth Shinn, and Dilip Wagle.

Finally, we thank Naomi Schneider, Summer Farah, and the rest of the University of California Press team for supporting this book project.

PART I

Crisis

CHAPTER ONE

Baseline

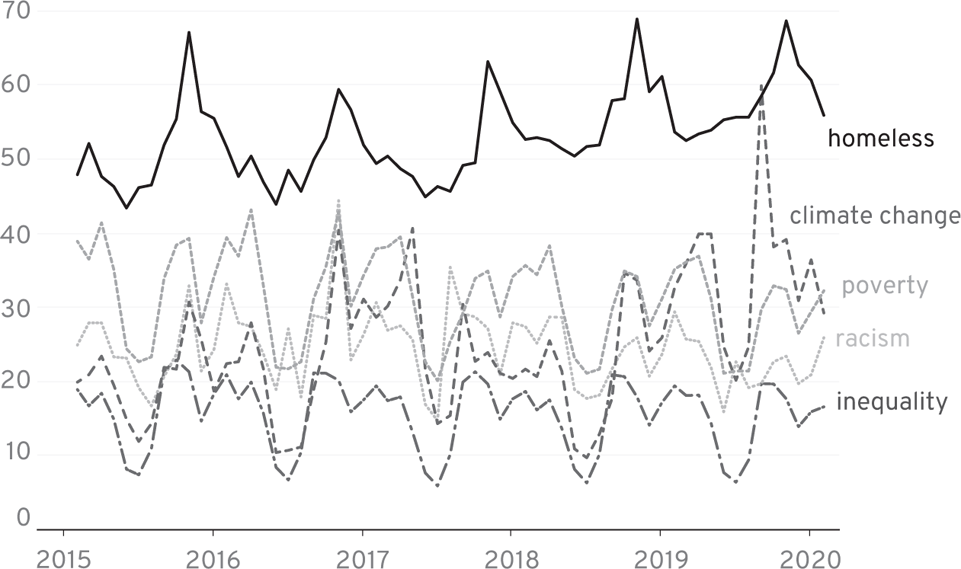

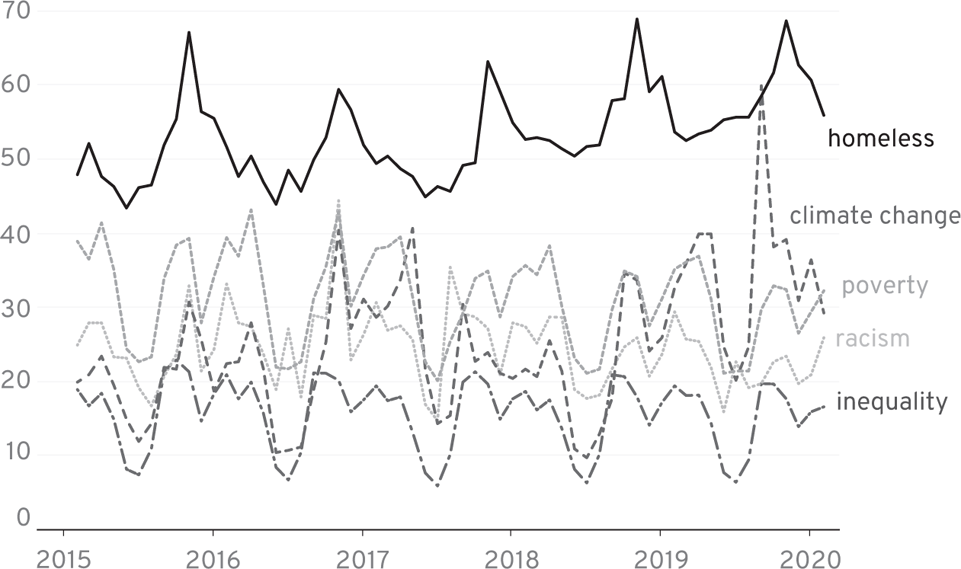

Homelessness occupies a prominent place in American political life. Although less than one-fifth of 1 percent of the U.S. population experiences homelessness on a given night in the country, the issue receives considerable attention from policy makers and the general public. This spotlight is striking given the scale of the homelessness crisis when compared to other prominent social problems. That fifth-of-a-percent figure translates to about five hundred sixty-eight thousand people. To be sure, this number should feel large and unacceptable. But on an absolute basis, for example, homelessness pales in comparison to the nations poverty crisis: Over thirty-four million Americans were living below the federal poverty line in 2019. Meanwhile, abundant evidence highlights the political preoccupation with homelessness. In 2020, a poll in Washington State revealed that voters ranked homelessness as the top priority for the state legislaturefar above other common public concerns like transportation, the economy, the environment, and health care.

Figure 1. Public interest over time for five search terms. Data source: Google Trends

How might we explain this seemingly disproportionate interest in the issue of homelessness? Two potential explanations come immediately to mind. First, maybe this interest isnt as disproportionate as it might initially appear. That is, maybe the numbers are wrong. Among astute observers, it is well understood that official point-in-time census estimates of homelessness underestimate the true size of the population experiencing homelessness on any given night. In light of these figures, it is more accurate to consider homelessness as a problem that affects millions, rather than hundreds of thousands. But even the larger figure highlights the fact that only a small fraction of people living in poverty actually lose their housing.

Next page