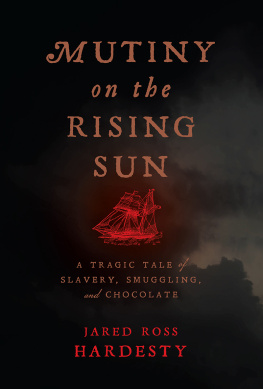

Mutiny on the Rising Sun

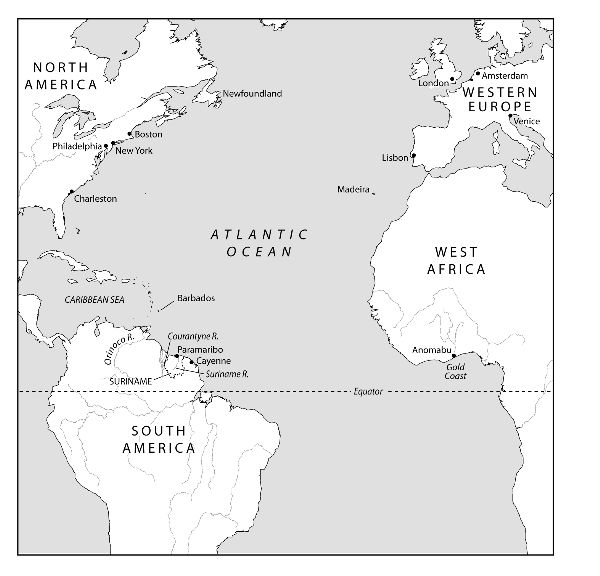

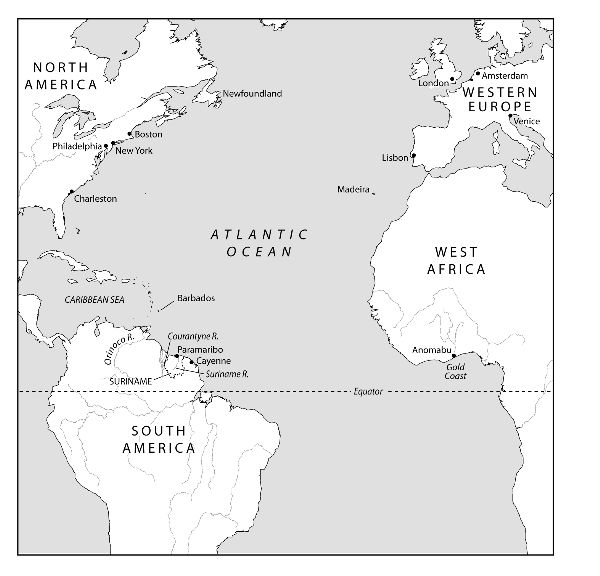

The Atlantic world. Map designed by Bill Nelson.

The Guianas. Map designed by Bill Nelson.

Mutiny on the Rising Sun

A Tragic Tale of Slavery, Smuggling, and Chocolate

Jared Ross Hardesty

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2021 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the publisher.

ISBN : 9781479812486 (cloth)

ISBN : 9781479813148 (library ebook)

ISBN : 9781479810215 (consumer ebook)

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

For my grandparents

Contents

Mutiny on the Rising Sun draws from a vast archive of original manuscript sources. During the eighteenth century, spelling, capitalization, punctuation, and grammar were not uniform. As such, when quoting from original English-language documents, I retain the original formatting. The book also uses Dutch archival documents. Since those have been translated into English, quotations from them are formatted following modern conventions. Likewise, many of the names found in the Dutch sources have been modified for accuracy.

Moreover, at the time of the mutiny in 1743 and until 1752, the British Empire remained on the Julian Calendar, while the Dutch (and most of Continental Europe) followed the Gregorian Calendar. Because of discrepancies in timekeeping, by the middle of the eighteenth century, the Julian Calendar was eleven days behind the Gregorian. When working on a case that spanned both calendars, this can create confusion. For example, the mutiny took place on either 1 June 1743 (Julian Calendar) or 12 June 1743 (Gregorian Calendar), depending on where persons lived and what calendar they followed.

To address this issue, in this book I render all dates by the Julian Calendaralso called Old Style as opposed to the Gregorians New Style. This decision is not to privilege the British over the Dutch but rather to standardize dates as they would have been understood by most of the colonial Americans involved with the case. Nevertheless, in chapters 5 and 6, which narrate the end of the mutiny and its aftermath, exact dates matter. In those chapters, dates are still rendered in the Old Style, but often followed by their New Style date in parentheses. When distinguishing between the two calendars in chapters 5 and 6, I use the abbreviations OS for Old Style / Julian and NS for New Style / Gregorian. Everywhere else, dates are in the Old Style.

The Julian Calendar differed in another way. The new year began on 25 March as opposed to 1 January. Most contemporaries made note of this, labeling all dates between 1 January and 24 March with both years, writing, for example, 15 January 1742/3. To simplify, this book considers 1 January the new year, although if the author of a manuscript document used both years, that will appear in the citation.

Finally, a significant portion of this book deals with issues of race and slavery. Only when absolutely necessary do I use eighteenth-century nomenclature for people of African and Indigenous descent. When discussing Native people, I am as specific as possible and use ethnic identifiers, avoiding broad terms like Indian and Native American. Indigenous people in the Guianas are referred to as Amerindians, and that term appears in the text. Terminology also matters for discussing slavery. For that reason, I generally use the term enslaved to refer to those captives held in bondage. Nevertheless, while I eschew calling enslaved people slaves as much as possible, doing so is sometimes difficult for stylistic reasons.

John Shaw stood at the helm of the schooner Rising Sun enjoying the cooler night air. After more than a week in the heat and humidity of Paramaribo, it was a welcome relief. It was eleven oclock on the night of 1 June 1743 and Shaw, the ships boatswain currently on watch, prepared to mark the passage of another day. Everything was calm and unremarkable. The captain, Newark Jackson, had just retired to his cabin. Hugging the northeastern coast of South America, the schooner lumbered eastward away from Dutch Suriname and toward French Cayenne.

The Rising Sun and its crew had just spent the previous week trading in Surinames capital Paramaribo. It was business that should not have been conducted. The schooner, having voyaged from the British West Indian colony of Barbados, entered Suriname under false pretenses. Claiming to need supplies and repair, the ship received permission to dock from the colonys governor, Jan Jacob Mauricius. Not a fool, Mauricius knew the schooner carried contraband and was there to offload its cargo in defiance of the law. International treaties, however, prevented the governor from denying distressed ships safe harbor. He commanded them to moor at Fort Zeelandia, Surinames seat of government, finish their repairs, buy their necessities, and make haste in leaving.

They did not leave immediately. The crew lingered for a week, selling the ships illicit cargo, while the captain and supercargo, or merchant, George Ledain visited old friends and trade associates. After days of malingering, Mauricius became so annoyed with the crew that he stationed five soldiers on board the Rising Sun to prevent any further contraband trade. Somehow, the illegal commerce continued. Jackson, meanwhile, kept telling the governor that the ship was in need of ever more repairs and the sailors ended up caulking the entire vessel while in Paramaribo. Even if the ruse was not particularly clever, one had to admire the crews dedication to it.

Finally, on 31 May 1743, the Rising Sun departed Paramaribo and used the Suriname Rivers current to leave quickly.

Early the next morning, the Rising Sun departed Suriname entirely and started to tack eastward toward Cayenne, the second and final destination before returning to Barbados. The day was totally uneventful. The captain, supercargo, and John Shaw were all veterans of the Suriname trade and had been on this route many times before. The ships mate, William Blake, was a skilled pilot and navigator, while the three Portuguese sailors Jackson hired in Barbados to assist with the voyage, Ferdinand da Costa, Joseph Pereira, and Thomas Lucas, collectively boasted decades of experience at sea. Although the trading venture was illegal in three different empires, it was at least routine and uneventful.

Or it should have been. As Shaw stood watch at the Rising Suns helm, one of the Portuguese sailors on duty with him, Pereira, engaged him in conversation. Pereira inquired about the ships compass and where each of the points on that compass led. The boatswain thought no harm of the conversation and explained that the uppermost point went to Orinoco in the Spanish colony of Venezuela. Tiring of the conversation, Shaw asked Pereira to fetch him a dram of rum. The sailor went down in the hold and returned ten minutes later with no dram but with more of the same questions. Shaw offered the same answers and Pereira returned below deck.

Next page