Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

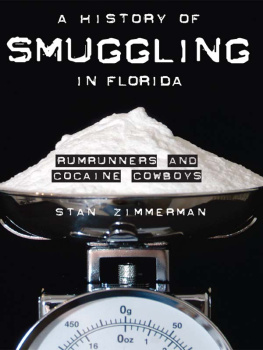

Copyright 2006 by Stan Zimmerman

All rights reserved

Cover art by Deborah Silliman Wolfe.

First published 2006

Second printing 2008

e-book edition 2012

ISBN 978.1.61423.356.5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zimmerman, Stan.

A history of smuggling in Florida : rum runners and cocaine cowboys / Stan Zimmerman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

print edition ISBN: 978-1-59629-199-7 (alk. paper)

1. Smuggling--Florida--History. I. Title.

HJ6690.Z56 2006

364.133--dc22

2006026777

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Floridas unique location, peninsular geography, poverty of natural resources and history of hustle produced this chronicle of illicit activity. Smuggling is a constant but unrecognized factor in Floridas steamy history. The navigator who found Florida was first a smuggler. Todays Florida governor is married to a smuggler of clothing and jewelry. Not to mention a previous governor who was a gunrunner.

It is a wild tale. A story of unconquered Native Americans. A story of the richest men in the world. A story of mud towns that became metropolises. A story of heroes and villains.

On one hand, we have desires; on the other hand, suppliers. And in between, stern government regulations. Nobody knows how many things are illegal to import. This bottle of rum is OK but that one is not. This jar of caviar is fine but next week its totally forbidden. The rules change daily. One aspect is constant: demand for contraband is strong and growing. Always has been, probably always will be.

Because smuggling is a covert activity, documentation is impossible to find until a smuggler is caught and indicted. Only then are records available, although what is made public is carefully sanitized. Because so many smugglers are never caught, the scope of their operations is nearly impossible to quantify.

Todays official guesstimates are staggering. The Federal Drug Enforcement Administration gives an annual rangefor illegal drugs onlyof $13.6 to $48.4 billion in 2005. The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston estimated in 2001 that $30 billion in illegal profits were laundered that year in the United States. The big numbertotal annual money laundering worldwide in 2001was estimated between $600 billion and $1.5 trillion. While those sums are profits from all illegal industries, most of them depend on smuggling.

Floridas fraction of both the national and global totals is unknown. But we know virtually everything worth smuggling hasat some point in timepassed quietly across Floridas borders, often by the ton.

My aim is neither to glorify nor vilify. My aim is to display a fundamental truth about Florida: it is a smugglers paradise. Smugglers developed Florida as we know it today and they are shaping its future for tomorrow. From the Governors Mansion to your next-door neighborhowdy, smuggler!

one

EVERYBODYS A SMUGGLER

It was the wee hours of a February morning. I was aboard the Sibelius Express between Moscow and Helsinki. The Berlin Wall was down, the Soviet Union collapsed and a shaky new Russia was rising from the wreckage. Winter snow covered the poplars streaming outside the window of my train compartment.

Suddenly there was banging on the door. Customs! Passports! The door slid open as I tumbled in my underwear from my sleeper. I was confronted with one of the ugliest women Ive ever seen. She looked like a toad dressed in a heavy wool uniform. Passport! she croaked.

I started to put on my trousers, but Niet! was her response, so instead I extracted my passport from my bag and handed it to her. We stood in silence while she flipped the pages, and then examined my hard-won visa on a separate sheet of paper. It had taken years to arrange that visa; its sponsor was the new Russian Ministry of Defense, for I was in the new Russia to interview ex-Soviet submarine designers.

That didnt cut any mustard with my early hours visitor. Declaration?! she nearly shouted. No, said I. Nothing to declare. She spun and motioned to four men in the carriage hallway. They entered the compartmentit was getting crowded nowand proceeded to take it apart. The ceiling came down, the seats and bed were disassembled: it was a practiced deconstruction, completed in only a few moments.

Toad lady surveyed the wreckage and then motioned for me to open my bag. I pulled down the zipper, and her eyes lit on a small oil painting Id purchased in St. Petersburg. Forbidden to export art from Russia! she said, as she lifted it between thumb and forefinger. Her bully-boys then attacked the bag with a vengeance, uncovering my other prizea catalog in French from the Pushkin in Moscow, the museum where all the impressionist paintings expropriated during the Russian Revolution ended up.

I purchased my small oil painting in a freezing rain outside the Hermitage museum in St. Petersburg for a pittance. I even asked for a receipt, a scrap of paper with a scrawl I couldnt read. Later I saw the exact same painting, in larger and smaller sizes, all over St. Petersburg. But I didnt mind, I still enjoyed my little seascape.

By now the compartment was chaos: my dirty clothes mingling with parts of the ceiling, my reporters notes fallen into the disemboweled bed, my shoes dangling from the luggage rack and my painting still between the thumb and forefinger of the toad woman.

She looked at the Pushkin catalog and then at my wee painting. I produced the receipt. She examined it carefully. She put the painting down and thumbed through the catalog. Art is good, she said, and walked out. I scurried to repack my belongings as the bully-boys rebuilt the compartment. Then they too were gone.

I waited for the cops to arrive and haul me away, but they never came. I arrived in Helsinki, painting intact, with the internal glow of a successful smuggler.

The Sibelius Express was not my introduction to smuggling. As a reporter, I served an apprenticeship in Florida and spent journeyman time here as well. Smuggling stories were at times an almost daily occurrence. As a broadcaster, I covered the transition from marijuana to cocaine. As a sailor in the Ten Thousand Islands of Florida, south of Naples, I observed the low-flying DC-3s bearing illicit cargoes over the Everglades en route to landings on the deserted streets of undeveloped proto-cities like North Port and Cape Coral.

On one trip, I witnessed the nighttime passage of an unlit ship reeking of human stench as it passed within a stones throw of my anchorage. It was an odorous reminder of slave ships in centuries past. Other times, Ive seen bales of marijuana bobbing like sea turtles in the Gulf of Mexico, jettisoned or lost overboard by midnight pot haulers. Yes, Ive been close to smuggling.

As a reporter, I covered trials of major cocaine smugglers, senior law enforcement officers and even a sheriff caught in the coils of smuggling. And years later, my community became involved in the story of a single orchid, smuggled out of Peru and ending up in a botanic garden that pled guilty to the federal crime of possessing a protected species. A friend is still in prison for selling Cuban cigars to the cognoscenti of Longboat Key.

Next page