Minarets on the Horizon

MUSLIM PIONEERS IN CANADA

Murray Hogben

2021 Murray Hogben

Except for purposes of review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form without prior permission of the publisher.

Published with the generous assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. We also acknowledge the support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Cover design by Sabrina Pignataro

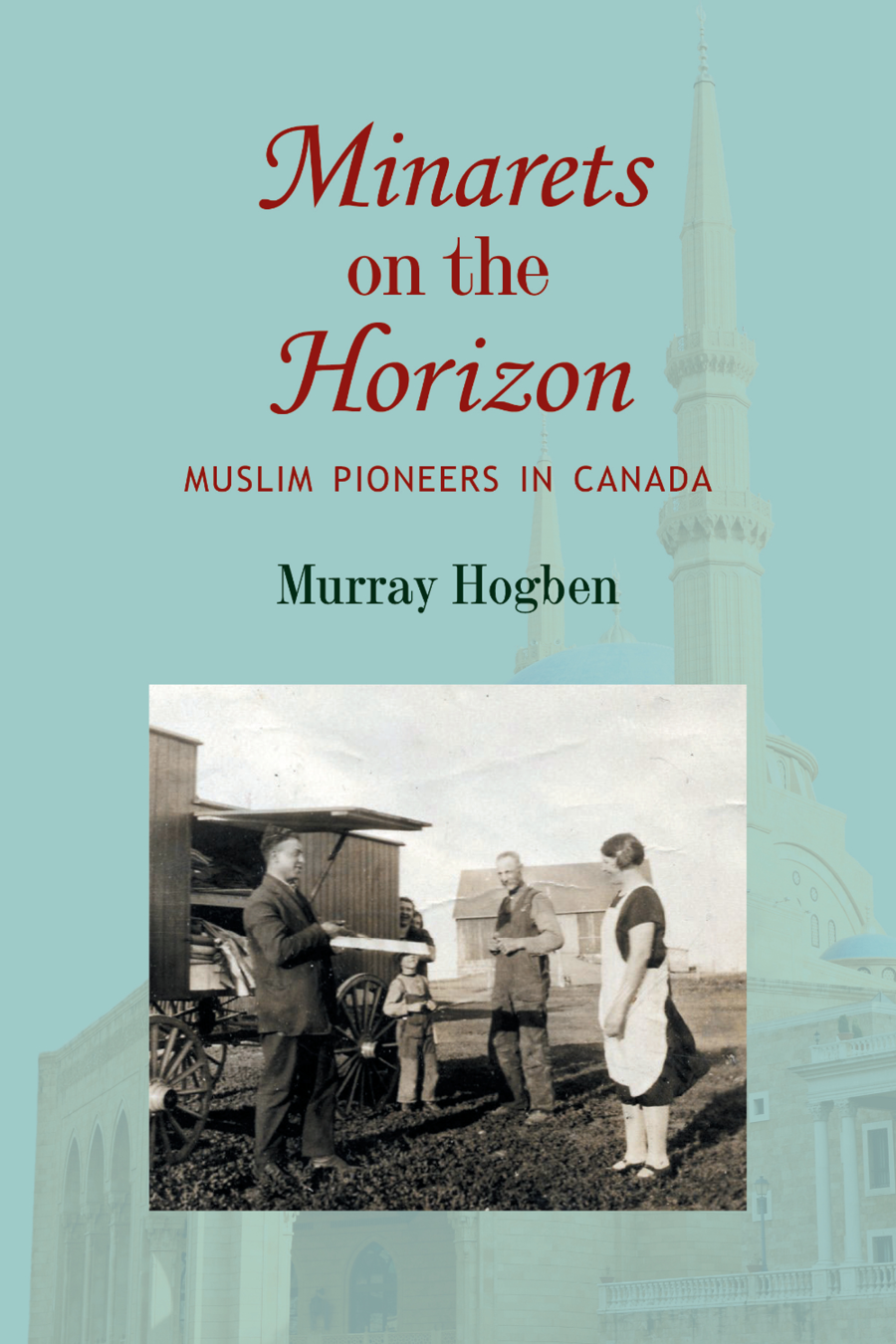

Cover images: Mohammad (Sam) Asiff peddling goods to Alberta farmers from his horse cart in 1930s, photo courtesy of Fisal Asiff; fmajor/Mohamed Al-Amin mosque, Beirut, Lebanon, stock photo /iStockphoto

Author photo credit: Bibijehan Henson

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Minarets on the horizon : Muslim pioneers in Canada / Murray Hogben.

Names: Hogben, Murray, author.

Description: Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20210148004 | Canadiana (ebook) 2021014873X | ISBN 9781774150320 (softcover) | ISBN 9781774150337 (EPUB) | ISBN 9781774150344 (PDF)

Subjects: LCSH: MuslimsCanadaHistory20th century. | LCSH: ImmigrantsCanadaHistory20th century. | LCSH: PioneersCanadaHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC FC106.M9 H64 2021 | DDC 305.6/970971dc23

Mawenzi House Publishers Ltd.

39 Woburn Avenue (B)

Toronto, Ontario M5M 1K5

Canada

www.mawenzihouse.com

To my wife Alia without whom the best parts of my life would not have occurred,

to our children Noorjehan, Ameera and Omar,

to our grandchildren Bibijehan, Shakoor, Isra and Reza,

to our son-in-law John Douglas Henson,

and to all the pioneers, recorded or not.

May God be pleased with them all.

The Carpet-Weavers Excuse

Back in 1979, I travelled across much of Canada to record interviews with some of my Muslim coreligionists, with the aim of documenting their experiences as immigrants, the challenges they faced, and their current conditions. At that time we numbered just short of 100,000, and the Council of Muslim Communities of Canada (CMCC) and the Canada Council had decided that such a survey would be worthwhile. But as time passed, I lost faith in myself to ever carry out this daunting project without the aid of institutional support, which I did not have. In 2011, an arson attack destroyed all of my tape recordings, partial transcriptions and paperwork. Fortunately much had survived in cyberspace. This was enough to compel me to pick up the project again. I added more material to it and completed it, though forty years later. However, I have long been concerned about memory lapses by myself and my ageing interviewees and about possible misunderstandings between us that could have affected the accuracy of this history.

As the famous poet and astronomer Omar Khayyam (10481131) wrote, in the rendition of Edward FitzGerald titled the Rubaiyat (18091883):

The Moving Finger writes; and having writ,

Moves on; nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.

To mitigate such a final and unforgiving judgment on my book, I make a plea for indulgence, using the oriental carpet-weavers excuse. According to a story, the weaver should make sure there is an obvious mistake in the work, because to weave a perfect carpet would be to challenge the perfection of God. In that sense, because of errors, I hope that God will be pleased with my efforts.

PART I

Introduction: The Project Since 1979

Moslems!

That was the word that the leader of our 1950s high-school clique picked as a useful derogatory term for losersany outsiders who werent part of our little group. Growing up in Ottawa, we had never met or seen a Muslim (the preferred spelling) before. What were Muslims like? Sinister Arabs besieging gallant French Foreign Legionnaires in a desert fort? Veiled harem women? Gunga Din?

A few years on, while I was finishing a bachelor of arts degree in English literature, I encountered Islam firsthand when I met a young Indian Muslim woman, Alia Rauf. She made such an impression on me that I became a convert in 1956, married her, and went on to become an active, practising Muslim and spokesman.

In 1961, there were less than 6,000 Muslims in Canada. Today there may be up to 1.5 million of us spread out across this country. As the secretary of the Muslim Society of Toronto in the 1960s and later of the Islamic Society of Kingston, I worked with Muslim groups into the 1970s and became connected to the Council of Muslim Communities of Canada (CMCC), which was founded in 1979. It was then that, with funding from the Canada Council, I began a project to record interviews with Muslim men and women from across the country about their lives as immigrants. In its final form the project, and this book, has become a record of the lives of Canadas pioneer Muslims.

The word pioneer, in the first place, refers to Muslims, or their antecedents, whose lives began in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Syria (which included present-day Lebanon) and Albania. They were the earliest Muslims in Canada. That was long before the liberalization of Canadian immigration policy in the late 1960s. A cursory reading of the evolving immigration acts from 1869 through the 1962 Order in Council shows a gradual move to eliminate overt racism in the laws. Finally, the 1967 Order in Council established the points system, which excluded race, ethnicity, and national origin from the conditions of admissibility to Canada. Education, professional skills, work experience, and knowledge of English or French were emphasized in the interests of Canadas economic and labour requirements. Although immigration officers retained some discretion, South Asians and others were no longer limited by quotas. An ever-increasing number of Muslim immigrants began arriving, and their families expanded.

To be clear, I am using the word pioneer in this work to mean those Muslims who had immigrated to Canada from the late nineteenth century onward through to those arriving before the critical year 1967 from a variety of countries, or were born here.

In this book, I am using Muslim to refer to all who self-identify with Islam to some degree to census-takers, friends, and others. The term includes those who practise the tenets of the faith with more or less rigour and sincerity, and also those who connect only culturally with other Muslims on occasions like weddings and funerals.

My only regret is that I havent had more time or energy to add other voices, those of more women and ethnicities and that cover a wider geographical area. This long-delayed work is far from perfectas I have admitted in my apologia. But my sense of obligation to old friends, the Muslim pioneers whose stories must be told, and the wider Canadian Muslim and non-Muslim communities, compels me to stop here, with the hope that others will carry on this work.