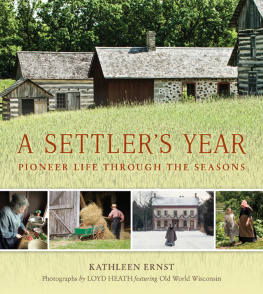

A Settlers Year

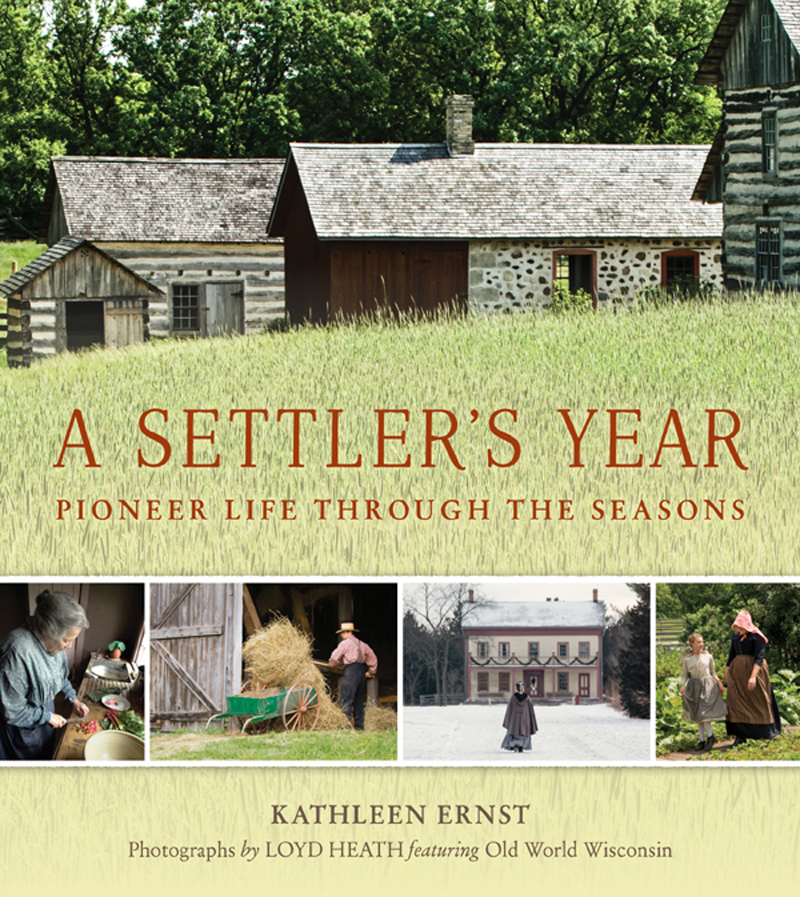

A SETTLERS YEAR

PIONEER LIFE THROUGH THE SEASONS

KATHLEEN ERNST

Photographs by LOYD HEATH

W ISCONSIN H ISTORICAL S OCIETY P RESS

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

Text copyright Kathleen Ernst, LLC, 2015

E-book edition 2015

For permission to reuse material from A Settlers Year: Pioneer Life through the Seasons (ISBN 978-0-87020-714-3 and e-book ISBN 978-0-87020-715-0), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

wisconsin history .org

Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Societys collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

Photographs copyright Loyd Heath 2015 unless otherwise credited

Designed by Percolator Graphic Design

19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Ernst, Kathleen, 1959

A settlers year : pioneer life through the seasons / Kathleen Ernst ; photographs by Loyd Heath.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87020-714-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-87020-715-0 (ebook)

1. Frontier and pioneer lifeWisconsin. 2. WisconsinHistory19th century. I. Heath, Loyd. II. Title.

F584.E76 2015

977.5'03dc23

2015005242

In memory of Marty Perkins:

scholar, colleague, mentor, friend

CONTENTS

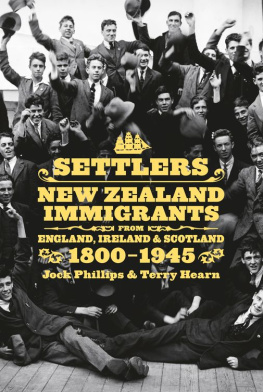

On a breezy, salt-scented day in the nineteenth century, a group of Bohemian immigrants with tearstained cheeks leaned over the railing of the ship that would take them to America. Someone began to sing Where Is My Home? Husky-voiced, the others joined in as their last glimpse of Europe faded into the horizon behind them.

Another day, an Irish boy with haunted eyes and hollow cheeks boarded a ship. He did not look back at the land so desperately ravaged by potato blight and famine. Pinned inside his pocket was the note his mother had scribbled on a scrap of paper before she diedthe name of an unknown uncle, and a single compass word: Wisconsin.

At a different dock, several German women gave the tail ends of fat balls of homespun wool to their weeping, shawl-wrapped mothers and sisters. The yarn unwound behind the immigrants as they trudged up the gangway to their ship and found space at the railing. When the ship left her moorings, the yarn unspooled all too fast through trembling fingers. Soon each woman on the deck felt her twisted filament slip awaythe last ephemeral link to everything dear and familiar. Dozens of strands billowed lightly over the water, fading from sight like the tail of some fearful mare galloping back to familiar pastures.

Sometime later a deeply indebted Swedish tenant farmer slipped ghostlike from home on a dark night and made his way to the nearest port. He left his family with nothing but a promise to send passage money when he could. Years would pass before the family could reunite.

Where is my home?

The question haunted thousands of Europeans a century and more ago. They were caught between all they had ever known and the unimaginablea new life

Some women spent months deciding how to squeeze necessities and mementos into sturdy wooden trunks. Others arrived in the New World with baskets and unwieldy bundles. All of them packedin addition to wool socks, linen sheets, dried peasdreams of a better life. (WHI IMAGE ID 4722)

Women struggled to keep their infants and toddlers clean, healthy, and safe during the long trip. Sea voyages meant cramped quarters, seasickness, and fresh water doled out in strictly rationed portions. Many mothers were homesick, worried, and exhausted before even beginning the journey from the Atlantic coast to Wisconsin. (WHI IMAGE ID 38123)

Some immigrants traveled alone; others took strength from friends, relatives, or neighbors who had chosen to journey together. Theyd all gambled that the trip would lead to a better lifeif not for them, for their children. In Wisconsin, the population rose from 11,000 to over 305,000 between 1836 and 1850. By then, one-third of the population was foreign-bornsome from Great Britain, some from Europe.

Behind the statistics were more than a hundred thousand unique people, each with her or his own hopes and heartaches. Schoolchildren can recite lists of push and pull factors that contributed to the mass immigration. Famine, wars and compulsory military service, political or religious oppression, lack of affordable or arable land, and primogeniture (which permitted only the eldest son to inherit land) prompted thousands of European children, women, and men to turn their backs on home and family; available land and glowing reports from early settlers and land agents lured them across the Atlantic. But many Polish immigrants, whose homeland was under Russian and German rule, summarized the reason for leaving succinctly: za chlebemfor bread. Thousands of desperate Poles saw no hope of preserving their culture, tilling their own land, or otherwise providing the most basic necessities for themselves and their children in the Old World. They came in search of a new home.

After surviving the ocean crossing, newcomers made the next leg of their journey in canal boats, sloops, or steamships; in rattling train cars or plodding wagons. Many aimed for Milwaukee, with its public lands office, opportunities for work, shops to replenish dwindling provisions, and growing pockets of ethnic settlement where manyespecially Germans and Irishtook comfort in the cadence of familiar language.

And certainly, some of the immigrants stayed in Milwaukee or ultimately settled in other burgeoning cities. Tradesmen seeking new customers, men with money looking for commercial opportunities, men without money looking for work on the docks or in a brewery, tannery, or butcher shopsome settled into urban life for good. Most people, however, took a deep breath, squared their shoulders, and plunged into Wisconsins prairies and woodlands. In 1850, less than 10 percent of Wisconsins population were urban dwellers.

Also traveling from the Eastern seaboard were Yankeesmen and women of English descent, many third- or fourth-generation Americans. Perhaps restless, perhaps adventurous, perhaps already feeling confined by growing populations, perhaps frustrated by rising land prices, they left friends and family in Maine and Vermont and New York to try their luck on the western frontier.

Many of these families had packed the latest mechanical innovation into their wagonsa new harrow, or the latest hand-cranked sewing machine. They brought a zeal for civic improvements and a dedication to democratic government. Albert Tuttle, who left his wife and son in Connecticut while he explored Wisconsin, made clear in a letter home his desire to transport what he cherished most: