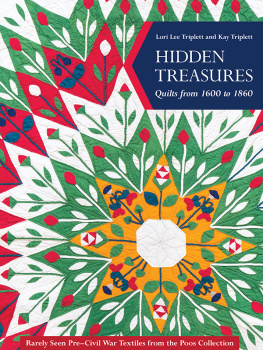

Publisher: Amy Marson

Creative Director: Gailen Runge

Editor: Liz Aneloski

Technical Editors: Deanna Csomo McCool, Sadhana Wray, and Linda Johnson

Cover/Book Designer: April Mostek

Production Coordinator: Zinnia Heinzmann

Production Editor: Jennifer Warren

Illustrator: Tim Manibusan

Photo Assistants: Carly Jean Marin and Mai Yong Vang

Photography by Diane Pedersen of C&T Publishing, Inc., unless otherwise noted

Published by C&T Publishing, Inc., P.O. Box 1456, Lafayette, CA 94549

Dedication

To the pioneers, who blazed a trail for us to follow, wrote journals or diaries for us to explore, and left textiles as a legacy of artistry for us to love.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to everyone who continues to support our quilting journey.

INTRODUCTION

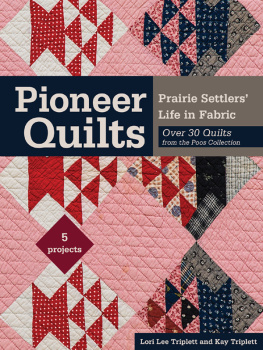

In January 2014 we attended the Tokyo International Great Quilt Festival in Japan. At that time we met with quilt festival planners to see if they would be interested in any exhibitions from the Poos Collection, such as the Chintz Quilts exhibition. Several months later we were amazed when the planners asked if we could tell the American pioneer story through quilts. It started us on a journey of discovering more about our family, more about the plains, and more about the Great Migration.

The Great Migration

The United States of America made the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, The Louisiana Purchase meant even more land was available for exploration and ownership for those able to pay. By 1800 the minimum number of acres a settler could purchase under the Land Ordinance of 1785 had been halved, to 320 acres, and settlers were allowed to pay in 4 installments, making land ownership a reality for a few more. In 1804 the required minimum acreage was halved again. The Homestead Act of 1862 made property ownership possible for many more by requiring settlers simply to file a claim and improve the land for 5 years.

A covered wagon on the Oregon Trail

Photo by Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives

Originally the westward course of expansion was the Missouri River, with travel dominated initially by canoes or small boats and later with steamboats. Over land, the Santa Fe Trail, pioneered by William Becknell in 1821, served as a main trade route for merchants from Independence, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico. Beginning in 1830, the Great Platte River Road was the convergence point of many routes (Trappers Trail, Oregon Trail, Mormon Trail, California Trail, Pony Express route) and a superhighway of westward expansion.

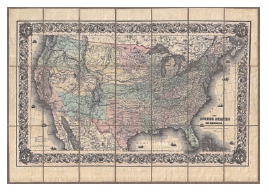

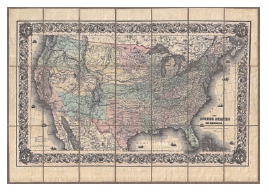

1855 Colton pocket map of the United States, created by Joseph Hutchins Colton

Photo of printed cartograph by Geographicus Rare Antique Maps

According to historian Merrill Mattes, pioneers may be divided into three main categories: soldiers who occupied the military posts and conducted government business;

This is the group of people that we focus onthose mothers, daughters, sons, and fathers who left behind family and friends to travel to a new place and create a home. Myths about the great trek started quickly, with writers who may never have taken the trip creating stories about it. The tall tales have continued, enhanced by Hollywood. Instead of relying on the myths, this book is supported by historical research, records of friends and family who lived during the nineteenth century, and other primary sources. More than 2,000 diaries exist from the period, reproduced faithfully in book collections or published by individuals. Finally, state and local historical societies have among their holdings diaries, letters, and notes.

Hollywoods version of the well-equipped, happy pioneers in the movie Santa Fe Trail, with Ronald Reagan, Errol Flynn, and Alan Hale Sr.

Photo by Film Archive

Preparation

According to the diaries, pioneers preparations for the trip tended to follow one of three different philosophies, each with positives and negatives.

In the first group were those who simply chose to sell all their possessions and travel lightusually individual travelers. By taking less, a pioneer could make better time and be less likely to experience a few of the hazards of the trail, such as theft. But travelers taking this approach might not have the supplies needed to survive, because stores and places to stay were not available to strangers in the early part of the century.

The second group adopted the opposite extreme, taking every possession and buying more, planning to be prepared for anything. But as wagons broke down or the weight proved to be too much for the livestock hauling it, many of these belongings were simply left by the side of the road. Trading or selling the extra items was rarely successful, because others knew that if there was excess, it would likely be left behind. Anything left by the side of the road could be claimed for free after the owner departed.

The final group were those pioneers who elected to take a minimal number of items but selected those carefully. If available, information from someone who had already made the trek often proved vital. Some diaries and other sources mention the wagon master, a guidebook, or letters from others who had successfully completed the journey. This group of pioneers appears to have been the most successful in making it to a new place to improve their fortune.

Susan Shelby Magoffin (18271855), the wife of a trader, who traveled the Santa Fe Trail in the 1840s and left a diary

Photo courtesy of the State Historical Society of Missouri

These preparations took from many months to up to a year to complete and were frequently difficult. There were wagons, livestock, weapons, and tools to prepare. Pine boards for coffins were also sometimes included in the preparation, because it was considered unlikely that everyone embarking would survive the journey. Fruit and vegetables were dried, and meat was salted. Flax was grown, and cotton was gathered and turned into homespun cloth to make tents, wagon tops, sheets, and death shrouds. Georgia L. McRoberts, whose family moved from Mississippi to the South Platte Valley, wrote about the preparations: Mother got cotton and wool which she carded, then spun; dyed and wove yard after yard of sheets, bed spreads, dress goods and even jeans for mens pants.

A woman using the spinning wheel

Scanned book illustration courtesy of Internet Archive Book Image

Keturah Belknap wrote, Will spin mostly evenings while my husband reads to me. The little wheel in the corner dont make any noise. I spin for Mother B and Mrs. Hawley and they will weave; now that it is in the loom I must work almost day and night to get the filling ready to keep the loom busy.

The Journey

After the preparation, the journey itself would be arduous, because most pioneers walked at a pace of ten to fifteen miles a day. The covered wagons were full of supplies, so unless serving as a driver, the pioneer walked beside the wagon so as not to add to its weight. Horses were a luxury; unless the pioneers were wealthy or the horses were used for work, rarely was a family able to ride horseback.

Next page