Publisher: Amy Marson

Creative Director: Gailen Runge

Art Director: Kristy Zacharias

Editor: Liz Aneloski

Technical Editors: Sadhana Wray and Helen Frost

Cover/Book Designer: April Mostek

Production Coordinator: Zinnia Heinzmann

Production Editors: Katie Van Amburg and Alice Mace Nakanishi

Illustrator: Freesia Pearson Blizard

Photo Assistant: Sarah Frost

Photography by Diane Pedersen, unless otherwise noted

Published by C&T Publishing, Inc., P.O. Box 1456, Lafayette, CA 94549

Dedication

This book is dedicated to all the African textile artists that contributed their knowledge and artistry to the world. As more research progresses, we hope many more names will be revealed to allow these artists the credit they richly deserve.

Acknowledgments

Our sincere thanks to the following for their time and knowledge:

Linda Baumgarten, curator of textiles and costumes, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Andrea Feeser, associate professor, modern and contemporary art history, Clemson University

Jan Hiester, curator of textiles, The Charleston Museum

Kim Ivey, curator of textiles and historic interiors, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

W. Douglas McCombs, chief curator, Albany Institute of History & Art

Margaret Ordonez, professor, Department of Textiles, University of Rhode Island

William Volckening, The Volckening Collection

Jan Whitlock, Whitlock Interiors

Thank you for financial assistance for research expenses:

American Quilt Study Group, Lucy Hilty Research Grant

American Quilt Study Group, Meredith Scholar Award

Quilt & Textile Collections

INTRODUCTION

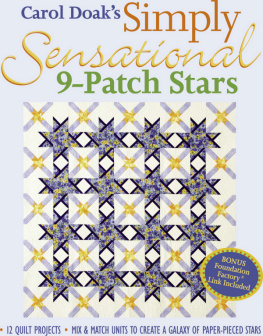

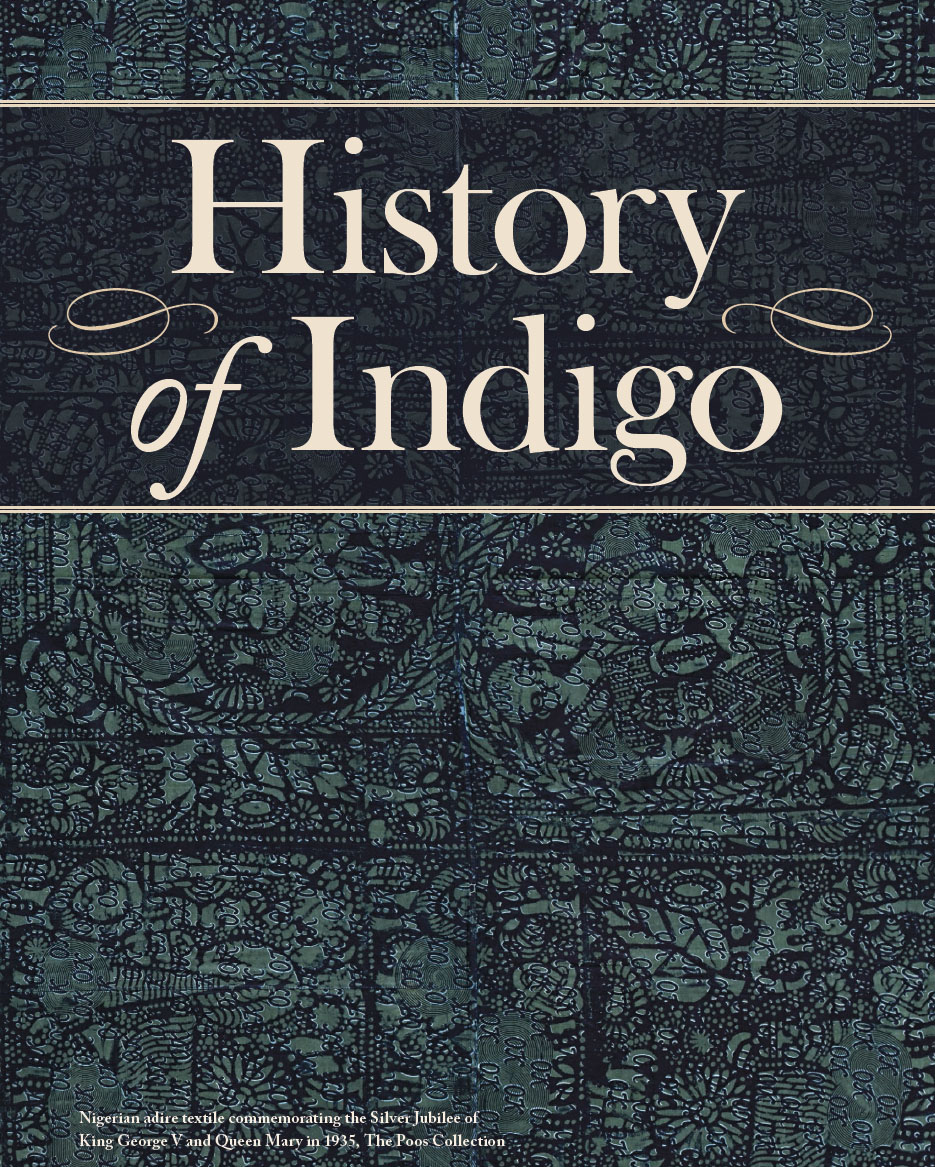

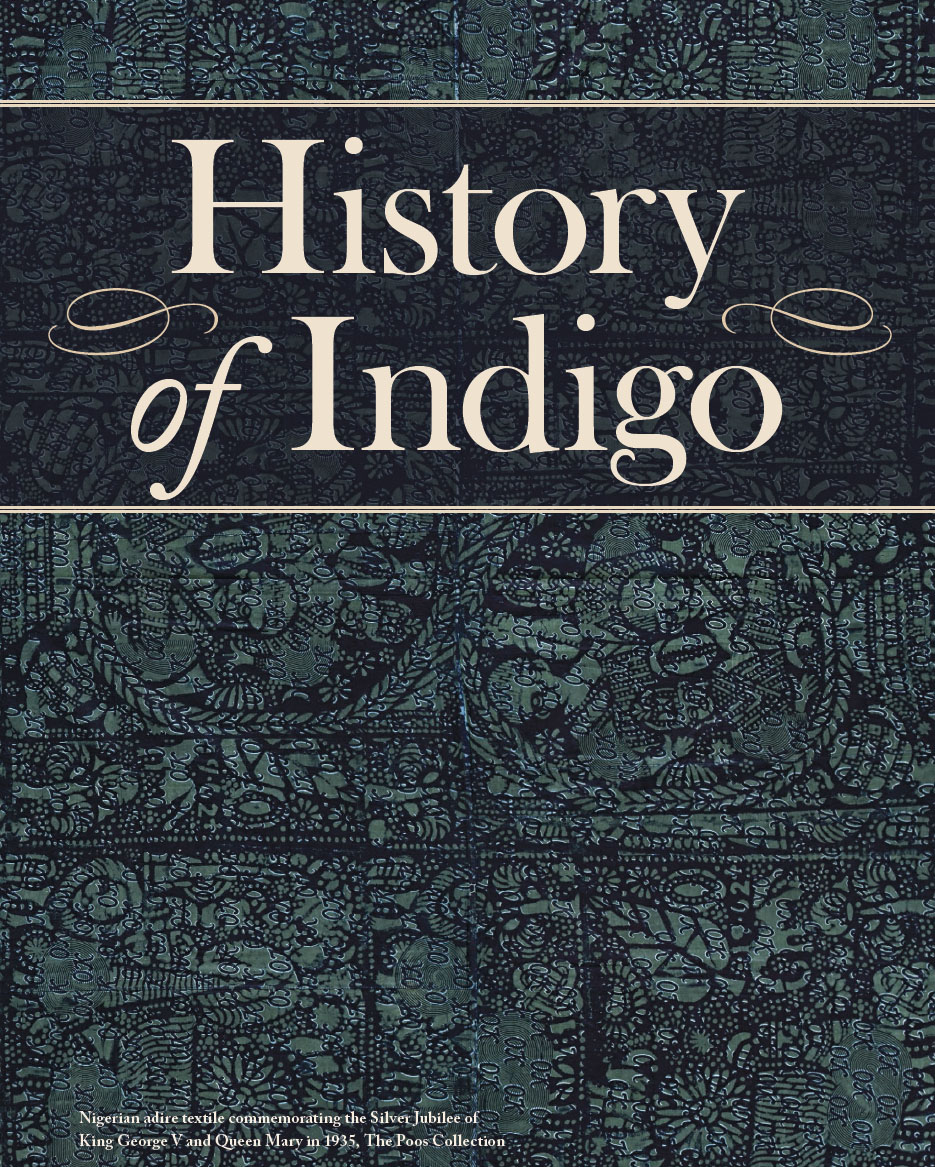

The Poos Collection was started in 1980 by Kay Triplett and has grown to be one of the largest privately held quilt and textile collections in the world. It is named for Martha Poos, a grandmother from Lancaster, Kansas, who quilted and instilled the love of quilts in her family members. The collection is well known for its emphasis on pre-1860 quilts, but less known for its extensive worldwide textile collection. It is a joy to present both wonderful quilts and historic African textiles together in this book.

When selecting the idea for our third book from the collection, indigo seemed the perfect theme. Blue is by far the most popular color in the world, and indigo is the king of that color. Indigo dye has been universally appreciated for millennia, from early Stone Age Africans to Renaissance European royalty to modern-day textile enthusiasts. Blue-and-white designs have been standard for centuries; colonial Americans chose that color combination for the blankets, bed hangings, and ceramics in their homes. They wore blue-and-white checked shirts, kerchiefs, and short gowns; blue-and-white striped jackets; and blue-and-white printed calico gowns.

The longevity of blue-and-white textile designs perhaps explains, in part, current interest in eighteenth-century indigo resist patterns (dubbed the mystery of historic textiles by Florence Pettit in her book Americas Indigo Blues). However, some of the fascination with these blue-and-white textiles may also be derived from their uncertain source, which has stumped researchers for decades. Many researchers have focused on Indias role in indigo cultivation, use, and trade. However, this book proposes that the people of Africa provided important, centuries-old knowledge of the dye when they were brought to the American colonies as slaves and came as free Africans in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

In May of 1956, the Cooper Union Museum and Smithsonian Institution of New York City (now combined into the Cooper-Hewitt Museum) gathered 50 experts from major institutions to examine and discuss more than 100 different blue-and-white resist textiles, representing about 65 different patterns.) For other researchers, this mark simply added more questions to the mystery. The experts left the gathering at the Cooper Union Museum without solid answers.

Through the decades, researchers continued to work on the mystery of indigo resist by testing the fiber content, speculating on the techniques used, and specifically identifying a couple of patterns as similar to those found in period sample books.

But the puzzle and the questions remain: Who made these textiles? What were the origins of the resist dyeing techniques? Did colonial Americans have the capabilities to produce this fabric? If so, then when was the knowledge necessary to make indigo resist textile designs transferred to this continent? Kay Triplett studied the textiles in West Africa and noticed parallels to the mystery indigo resist textiles, including similar bold designs in a white, light blue, and dark blue color scheme. The artists in Africa created the three-color scheme using very basic techniques, which meant the techniques could have been replicated in the colonial American environment.

The knowledge, as well as practice, of African resist and dyeing techniques led us to explore the African contribution to the world of textiles, particularly as it relates to indigo resist. India has long received the lions share of researchers attention regarding the cultivation, use, and trade of indigo. Instead, this book addresses the African artistry and love of textiles from the beginning.

Indigo and indigo resist are explored through the historic antique quilts of the Poos Collection. Quilters before the twentieth-century publication of blocks tended to have very individualistic names for the patterns. For ease of the reader, block names associated with the quilts (made popular in the 1930s) and later standardized have been used in this book. It is also important to remember that unless there is specific provenance, the quilts could have been made by someone beyond the typical female of European descent. African-American quilters are not simply defined by the Gees Bend style or colorful patchwork; they also made traditional patterns, with different types of techniques. Examples of the variety in African-American-made quilts can be found in many major museums.

Following the trail of an enslaved people is frequently difficult because, as they say, history is written by the conqueror. So sometimes the clues left behind are circumstantial; these are still presented in this book, because circumstantial evidence is an accepted form of proof in our society. However, we recognize there is still much research to be done, more names to uncover, more history to reveal. Therefore there are frequent endnotes included, to allow others to build on our research and put more pieces of the African influence puzzle together.

INDIGO: AFRICAS GIFT TO THE WORLD

Origins in Africa

The contributions of the African continent to the history of textile use and decoration often have been neglected.

Indigofera tinctoria growing in western Africa

Photo by Kay Triplett

It is a genus with a wide variety of more than 700 species; more than 300 species have been recorded in Africa alone. Indigofera grows naturally only in tropical regions, but cultivation of the plant has extended the range greatly over time.

Early evidence of art and painting on the African continent exists from Stone Age painting kits excavated from the Blombos cave in South Africa. These kits date from about 100,000 years ago and show that

Next page