INDIGO IN

THE ARAB WORLD

INDIGO IN

THE ARAB WORLD

Jenny Balfour-Paul

First published in 1997

by Routledge

Reprinted 2004

By Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Transferred to Digital Printing 2006

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

1997 Jenny Balfour-Paul

Typeset in Sabon by LaserScript, Mitcham, Surrey

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or

reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,

mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter

invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any

information storage or retrieval system, without permission in

writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book has been requested

ISBN 070070373X

Frontispiece Indigo dyer at Bayt cAbud, Zabid, Yemen

Publisher's Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint

but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent

Dedicated to my mentor

the late Susan Bosence

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Photographs were taken by the author unless otherwise attributed.

Plate 1

Plate 2

Plate 3

Plate 4

Plate 5

Plate 6

Plate 7

a dark colour; September 1995. The yarn is woven locally into cloth with red border stripes, melia, worn as shawls and skirts by women of the Sahel and Cap Bon regions.

Plate 8

Plate 9

(b) and (c)

Burnishing indigo-dyed cotton with a smooth stone to produce an iridescent sheen resembling carbon paper. Left Awad al-Mutara Ahmad Dhali of al-Bayda, Yemen, December 1983, and right Amer Salim Salem al-Shemani of Bahla, Oman; March 1985.

Plate 10

Plate 11

Plate 12

Plate 13

Plate 14

London 1989). Courtesy British Museum, Dept. of Ethnography:1967 AS2 15.

Plate 15

Plate 16

Frontispiece

Maps

NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION

The subject of this book is not one in which a rigorous system of Arabic transliteration has been judged necessary. This is partly because of the high incidence of colloquial Arabic (sometimes very localised) among the terms used, and partly because some of the words may, in fact, be borrowings from other languages. Nevertheless, the transliteration used is as consistent as these factors allow. The cain [c] is always shown while the hamza [] is shown whenever it occurs in a significant position. ta marbuta [t] is shown only where it is pronounced.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I should like first to thank all those in the Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies, and in the Centre for Arab Gulf Studies, at Exeter University, who have taken an interest in my research work, especially the late Professor M.A. Shaban, who enabled me to visit Oman and the United Arab Emirates, and Professor Ian Netton, now of Leeds university. I owe a great deal to my supervisor, Brian R. Pridham, former Director of the Centre, for his encouragement and help with my PhD thesis, upon which this book is based, and to his secretary, Jennifer Davies, and the staff of the Centre's Documentation unit, Ruth Butler, Parvine Foroughi and Bobby Coles. Thanks are also due to the staff of Exeter University library, particularly Heather Eva and Paul Auchterlonie, and to the University authorities for awarding me an Honorary Research Fellowship since 1993.

I am grateful for the help I have received from many people elsewhere in a wide range of disciplines, but should like to single out the following for the especial encouragement they have given me: the late Albert Hourani, Dr. Jim Bynon, Dr. Shelagh Weir, Peter Clark, Gigi and Roddy Jones, Francine Stone, Dr. Liz Wickett, Hussein Cherine, Doreen and Leila Ingrams, Clara Semple, Jacqueline Herald, Professor Lutfy Boulos, Dr. Ruth Barnes and Dr. Dominique Cardon. It was the warm support of the late Professor R.B. Serjeant that gave me the impetus to widen my research after my initial fieldwork in Yemen. My initiation into the mysteries of the indigo dye vat was thanks to the late Susan Bosence, who subsequently urged me to study the dyers of Yemen and elsewhere. She has been the inspiration behind all my work on indigo, and she died on the day I completed this manuscript.

I much appreciated the patience, generosity and hospitality of all those working or connected with indigo in the countries where I undertook my fieldwork, particularly from the farmers and dyers whose work is recorded in this book. Muhammad cAli cAbud, Ahmad Sacd al-Hakami and the al-Waqidi family of Zabid, Professor Khaled Maghout and Mahmud Hreitani in Aleppo, Dr. M.S. al-Amudi, Rector of Aden University, Omar Bamatraff in Aden and Professor Naceur Ayed at Tunis all helped me greatly.

Any errors and omissions in this book are due to my own shortcomings.

I am grateful to the following grant-making bodies who awarded me grants to help ease the expenses of research the Elmgrant Trust, Dartington; the Dyers Company, London; the Gilchrist Educational Trust, London; and the University of Exeter.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge my long-suffering family. My children, Finella and Hamish, and my mother, Jill Scott, have put up with my indigo obsession over many years. But above all, without the constant support of my husband, Glencairn (advisor, critic, translator of Latin and Arabic, and companion) this book would never have been completed.

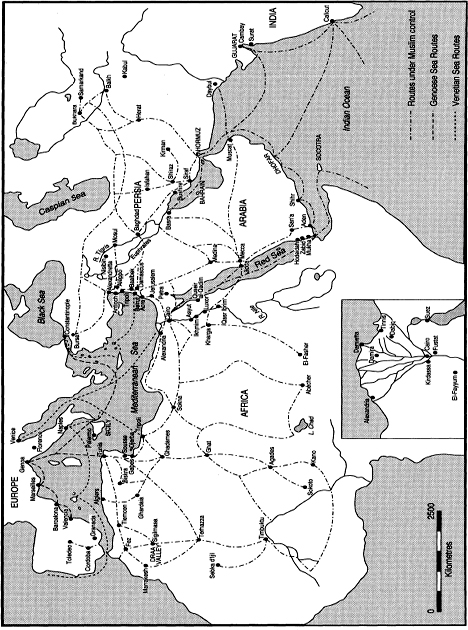

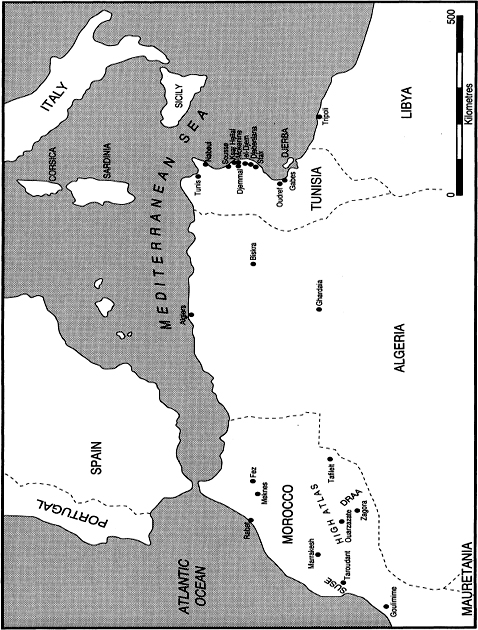

Map 1 Main trade routes and textile centres in the Arab world Mediaeval and later (inset, Nile Delta)

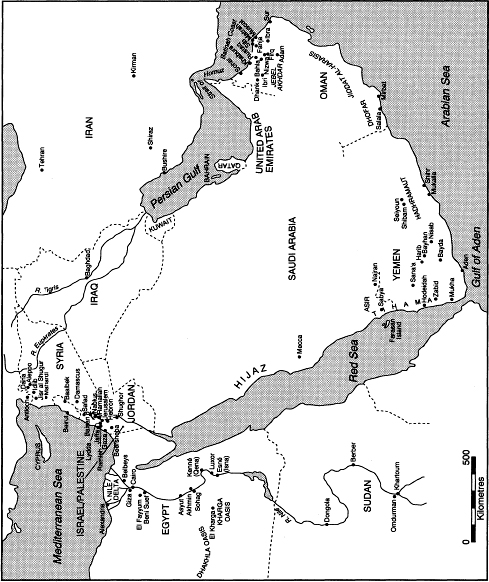

Map 2 Arab centres of indigo production and dyeing from the Middle Ages Middle East

Map 3 Arab centres of indigo production and dyeing North Africa

INTRODUCTION

Indigo, from whatever plant source, was the most important and universal natural dyestuff known to man from prehistoric times; without it, mankind would have had almost no source of blue dye colour until the invention of synthetic dyestuffs in the second half of the nineteenth century. Its synthetic substitute remains popular, most notably for the dyeing of blue jeans.

The role indigo has played in the history of many parts of the world has been fairly well documented, but in the case of the Arab world, where indigo dye has been in continuous use for over four millennia, little or no thorough investigation has been previously undertaken. This book sets out to provide as comprehensive a coverage as possible of the subject in all its aspects, from its earliest history to the present day. Although the study is of a particular substance, the approach is multi-disciplinary. It grew out of a desire to record the indigo industry of the Red Sea coastal plain of the Tihama, in Yemen, before its inevitable demise, after learning that the number of dye workshops in Zabid (already famous for indigo-dyeing in the Middle Ages) had dwindled from over one hundred in 1960 to just two in 1983, the year of my first study visit. Subsequent historical research on indigo in Yemen was carried out in UK. Encouragement to expand on this study led to further field trips to all the principal countries concerned, including return visits to Yemen, as well as to extensive library and museum research, discussion with those working in related fields and my own practical experience of dyeing with indigo, both natural and synthetic, and cultivating temperate and tropical indigo plants.