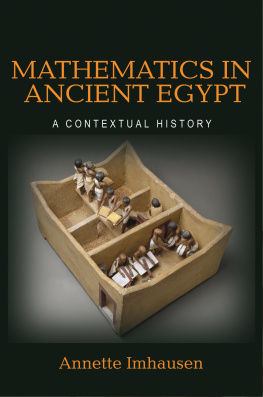

Analyzing Collapse

The AUC History of Ancient Egypt

Edited by Aidan Dodson and Salima Ikram

Volume Two

Analyzing Collapse

The Rise and Fall of the Old Kingdom

Miroslav Brta

The American University in Cairo Press

Cairo New York

This electronic edition published in 2019

The American University in Cairo Press

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

200 Park Ave., Suite 1700 New York, NY 10166

www.aucpress.com

Copyright 2019 by Miroslav Brta

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 977 416 838 3

eISBN 978 1 61797 960 6

Version 1

Contents

Preface

I rst came to Egypt in 1991 as an undergraduate student of Egyptology and prehistoric archaeology at Charles University in Prague. The fall of that year was my rst excavation in Abusir, a rural site among the pyramid elds, but one of the principal sites of the Old Kingdom period. It proved to be crucial for my future career in many ways.

There I experienced the thrill of observing how monuments, built millennia ago and now fallen into oblivion, were reappearing from the sands of the desert. Such discoveries challenged my imagination and my ability to piece together small fragments of evidence to build a picture of the past. Step by step, as the days passed, the ancient Egyptian world was becoming more and more tangible. Destinies of individual ofcials were gaining more concrete contours. Their fates started to ll in the outlines of the world they lived in and which they helped to shape. Individual lives of long-forgotten Egyptian ofcials of both high and lower standing, together with the general characteristics of the Old Kingdom society, were merging together; the micro- and macro-worlds started to form a unied and tightly interwoven whole. It took me quite a long time to reach this level of perception, and I have no doubt that to arrive at a complete state of knowledge and understanding of such a complex society is utterly impossible. This book is an attempt to offer my present perspective on one of several important periods of ancient Egyptian historyone of the rst complex civilizations in the history of this planet. This book is a kind of interim testimony to the development of that society.

But ambitious as this sounds, there is yet another aspect of this pursuit that I wish to share: individual archaeological discoveries represent an indispensable micro-world from which a general picture of historical processes several centuries long may be reconstructed. Ancient Egyptian evidence may be viewed from the longue dure perspective. This is an approach formulated by the French School of Annals; it refers to the study of history through mapping and analyzing evidence for specic historical processes over long periods of time, combined with individual historical events and with a strong multidisciplinary component.

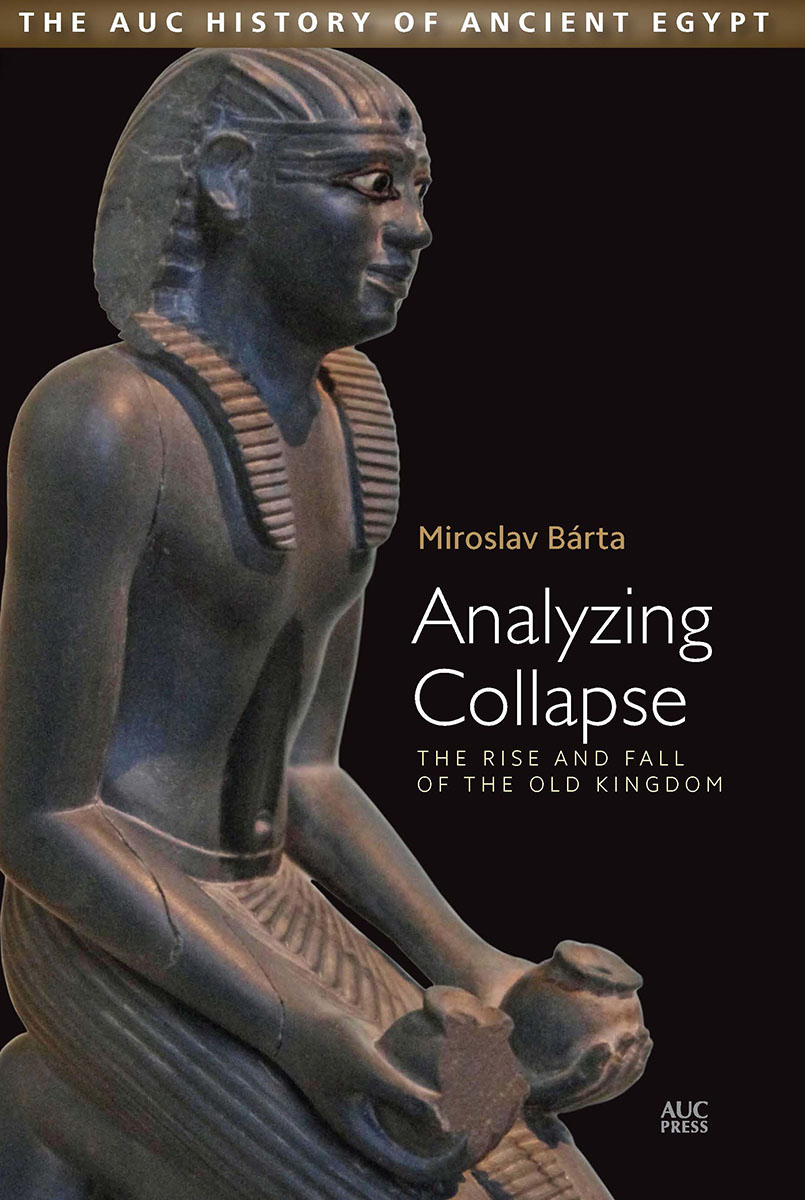

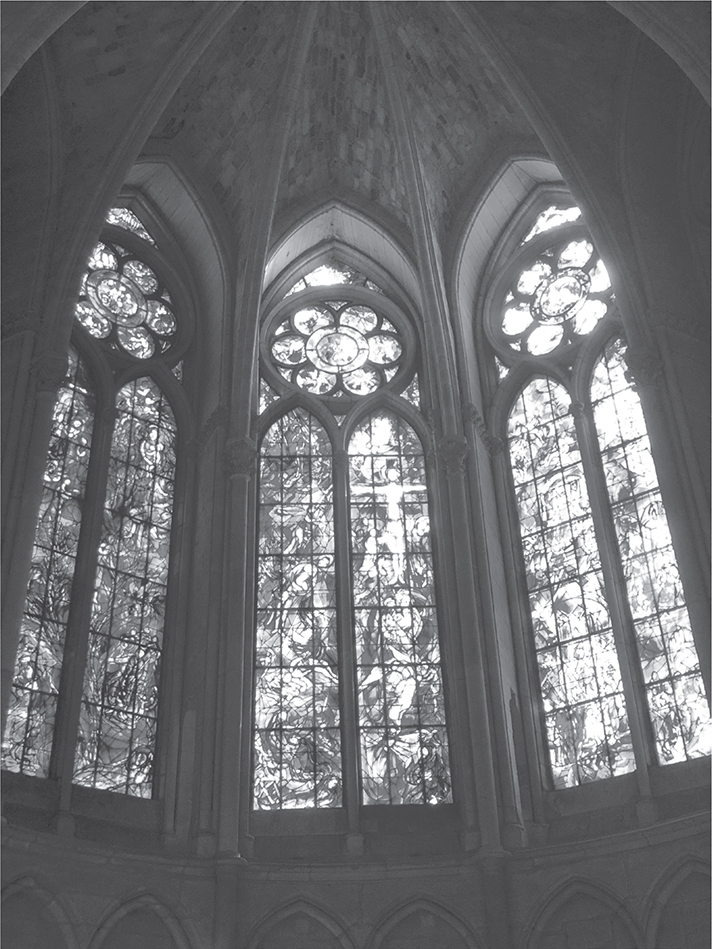

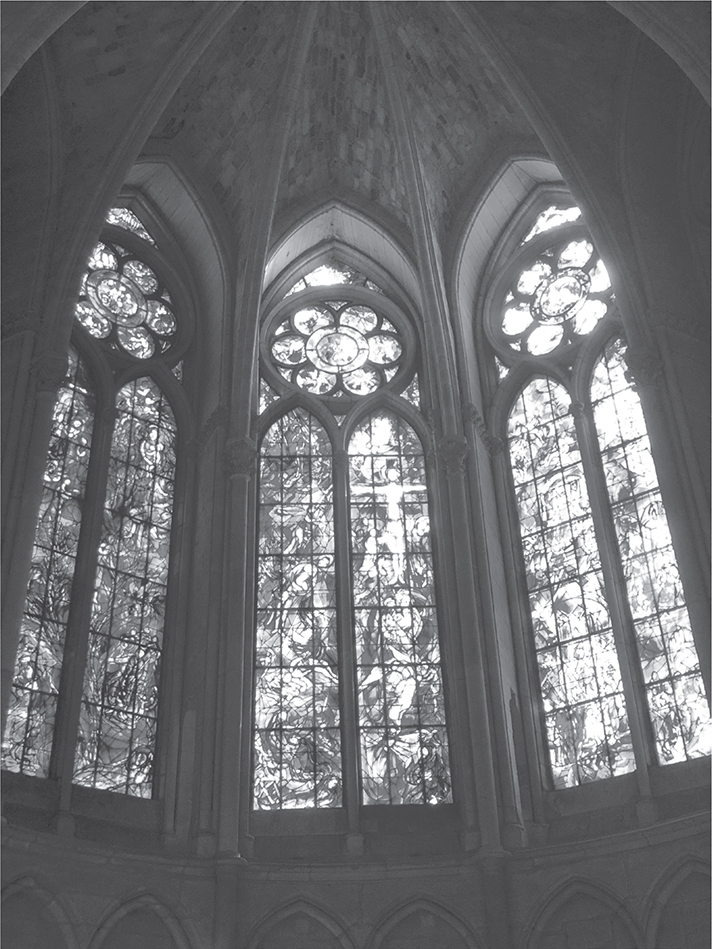

Fig. 0.1. Visual metaphor of modern study of history. Tiled windows in the cathedral in Rheims by Marc Chagall. In order to create such impressive windows, each of the colored tiles must be carefully produced; each on its own would be meaningless. To understand any civilization one must do the samecombine single events and longue dure analysis. (M. Brta)

Therefore, my focus throughout the book will be the following seven rules, which appear to form the essence of every civilization of which we have knowledge, and which can be distilled from comparative study of complex civilizations and longue dure history.

Law One

Every civilization is dened in space and time. It has geographical borders and temporal limits. Archaeology and history are the disciplines that analyze the emergence, rise, apogee, crisis, eventual collapse (understood as a sudden and deep loss of complexity), and the transformations leading to their new evolution. The making and unraveling of any civilization is a procedure that emphasizes the idea of time and process in combination with human agency.

Law Two

Every civilization develops by means of a punctuated equilibria mechanism, according to which major changes happen in a non-linear, leap-like manner when the multiplier effect is present. Once periods of stasis separating individual leap periods become shorter or disappear completely, one expects a major systems transformation, most often a sudden and steep loss of complexity (metaphorically called collapse).

Law Three

Every civilization uses a language that is universally understood by its members (its lingua franca, typically English in our Western world) and a commonly accepted system of values and symbols. Every civilization has major centers characterized by a concentration of population, monumental architecture, a writing system (in most cases), sophisticated systems of communication, systems for storing and sharing knowledge, a hierarchically shaped society, arts, and a division of labor. It also has the ability to redistribute main sources of energyin other words, it has elites who are able to establish and maintain the so-called social contract and allow the majority of the population to share in the prots generated by the system, which is controlled by a minority with decisive power.

Law Four

If the prevalent tendency within the civilization favors consumption of energy over producing it and investing it in a further increase of complexity, there is a declining energy return on investment (EROI). It means that a coefcient gained from the amount of energy delivered by a specic energy resource (such as water, sun, atom, gas, or coal) divided by the amount of energy necessary to be used in order to obtain that energy resource is becoming less and less signicant , and therefore less economically protable. As a consequence, the original level of complexity cannot be sustained or expanded. Eventually, in leaps rather than gradually, the system will lose its existing complexity and implode. This is what is traditionally and inaccurately called a collapse.

Law Five

Individual components of a given civilization proliferate and perish through inner mechanisms inherent in the society (changing bureaucracy, quality of institutions, role of the elites and technologies, ideology and religion, mandatory expenses, social system, and so on), and through the ability of the civilization to adapt to external factors such as environmental change. These are the internal and external determinants that shape the dynamics of any given civilization. They are in permanent interaction, in cycles of varying length.

Law Six

The so-called Heraclitus Principle has a major impact on all civilizations: the factors that promote the rise of civiliz ations are, more often than not, identical with those that usher in their collapse. Thus if we want to understand the precise nature and causes of the collapse, we must study not only the nal stage of the system but its very incipient stage, where the roots of the future crisis usually lie.

Fig. 0.2. Visual metaphor of a collapse. Impressive sarcophagus chest left behind in a corridor in the sacred animal cemetery of Serapeum, Saqqara, Egypt, Ptolemaic period. The sarcophagus, which was to contain the body of the sacred Apis bull, never reached its nal destination. The works, the faith, the legitimacy of the painstaking work ceased literally overnight; all workers and ofcials participating in this process walked away on a single day. This is what is typically called a collapsesudden loss of complexity, lack of economic means, lost legitimacy, and erosion of commonly shared values compromising the social contract. (M. Brta)