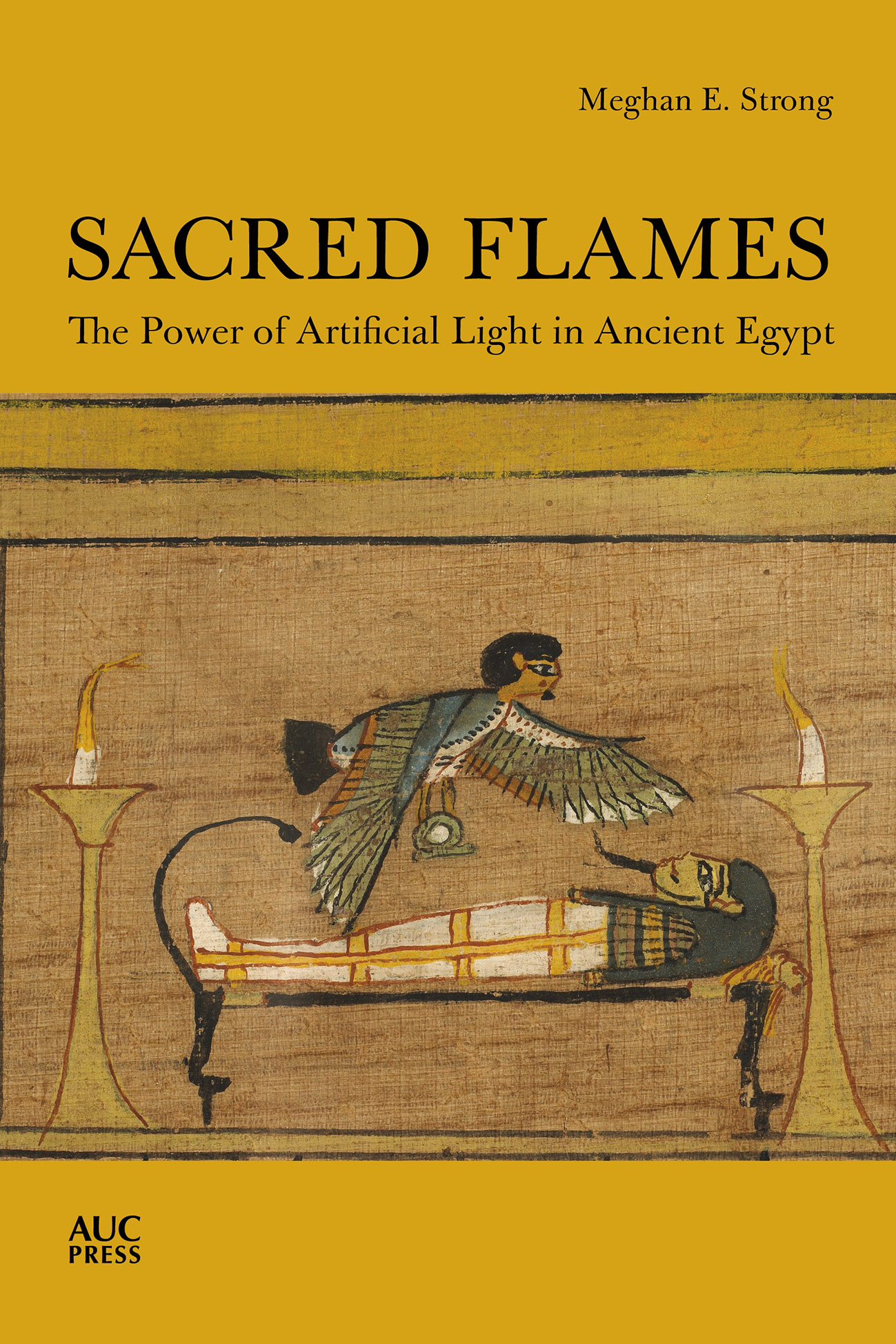

SACRED FLAMES

SACRED FLAMES

The Power of Artificial Light in Ancient Egypt

Meghan E. Strong

The American University in Cairo Press

Cairo New York

This electronic edition published in 2021 by

The American University in Cairo Press

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

One Rockefeller Plaza, 10th Floor, New York, NY 10020

www.aucpress.com

Copyright 2021 by Meghan E. Strong

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 649 03000 9

eISBN 978 1 649 03063 4

Version 1

Contents

Figures

Abbreviations

Aristotle | Aristotle. 1961. De Anima. D. Ross (ed.) |

BD | Book of the Dead |

CT | Coffin Texts |

Diodorus | Diodorus Siculus. 1933. Library of History, Volume 1: Books 1 2.34. C.H. Oldfather (trans.). Loeb Classical Library 279 |

FIFAO | Fouilles de lInstitut franais darchologie orientale |

Herodotus | Herodotus. 1972. The Histories. A.R. Burn (ed.) A. de Slincourt (trans.). Revised edition with new introduction. Penguin Classics |

L | Lexicon der gyptologie, 7 volumes. 197292. Wolfgand Helck, E. Otto and W. Westendorf. (eds.) |

LD | Lepsius, C.R. 1849. Denkmler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien |

MIFAO | Les Mmoires publis par les membres de lInstitut franais darchologie orientale |

MMA | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

o | ostracon |

p | papyrus |

Petrie Museum | Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, University College London |

Pliny | Pliny. 1945. Natural History, Volume IV: Books 12 - 16. H. Rackman (trans.). Loeb Classical Library 370 |

PM | Porter, B. and R.L.B. Moss. 2004. Topographical bibliography of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic texts, reliefs, and paintings; Vol. 1. The Theban necropolis Part 1. Private tombs. Second edition, revised and augmented |

PT | Pyramid Texts |

SAGA | Studien zur Archologie und Geschichte Altgyptens |

Strabo | Strabo. 1932. Geography, Volume VIII: Book 17, General Index. H.L. Jones (trans.). Loeb Classical Library 267 |

TLA | Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae |

Urk IV | Sethe, K. 1905. Urkunden der 18. Dynastie. 4 volumes. Urkunden des Agyptischen Alterums 4 |

Wb | Erman, A. and H. Grapow. (ed.) 192663. Wrterbuch der aegyptischen Sprache. 12 volumes |

Acknowledgments

T his book would not be in your hands if it were not for the encouragement and dedication of many wonderful people. First, a heartfelt thank-you to Nigel (to whom I wish a very happy retirement!), Anne, lfwine, Nadine, and the rest of the AUC Press team. You all have been a joy to work with and I am grateful for your patience and support of this project.

Kate Spence spent countless hours reading and editing this workand probably more hours picking me up off the ground and pushing me forward. This book would have been a poorer piece of research without her guidance and keen insight. Hratch Papazian calmly handled all my philological crises, for which I owe him much thanks.

Many light-hunting trips to museums and foreign countries were required during the course of this project, which would not have been possible without the generosity of many colleagues, including Laurent Bavay, Cdric Gobeil, Tracey Golding, Lila Janik, Liam McNamara, Adela Oppenheim, Alice Stevenson, Alice Williams, and the wonderful staff members of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, Ashmolean Museum, British Museum, and Metropolitan Museum of Art. I owe an enormous thank you to the staff of the Fitzwilliam Museum, particularly the researchers and collaborators on the Ancient Egyptian Coffins Project: Julie Dawson, Elsbeth Geldhof, Jennifer Marchant, and Helen Strudwick. Many colleagues, including Mariam Ayad, Janine Bourriau, Alan Clapham, Mennat Allah el-Dorry, Rene Friedman, Peter French, Sergej Ivanov, Friederike Junge, Giulio Lucarini, Cornelius von Pilgrim, Stephen Quirke, Pam Rose, Will Schenck, Anna Stevens, Nigel Strudwick, Kent Weeks, and Penny Wilson shared their knowledge, skills, references, and site material over the course of this project and I benefited greatly from their insights.

I am extremely fortunate to have wonderful friends and family who have loved me, encouraged me, humored me (by walking around my backyard with flaming torches and helping with other pyrotechnic experimentsthank you Helen, Ivan, Matt, and Rune), and pushed me on whenever I needed it. I also lucked out by having a husband who graciously dealt with our house smelling like a greasy burger shack and believed in me every step of the waythank you, Drew.

Introduction

O n April 29, 1879, my hometown of Cleveland, Ohio, became the first city in the United States to use electric street lighting. This was a momentous occasioncelebrated with a gun salute fired over Lake Erieand was one highlight in a flurry of lighting innovations that occurred during the nineteenth century. About the same time, Paris, London, and other cities around the world made the switch to electric street lights. This was the dawn of a new era, ushered in by the rise of the gleaming, clean lightbulb. What was a revelation in the late 1800s is now taken for granted. At the flick of a switch, light is always at our fingertips. We have forgotten that the invention of electric light marked a significant shift in our human experience. For millennia prior to the 1870s, artificial light required firea live flame that flickered and smokedand required constant maintenance and ample fuel. This dynamic light source also contributed to the environment and atmosphere in which people lived and worked. Homes were dimmer and smokier, flames sparkled across reflective surfaces, families gathered around candlelit tables, lives were marked by the lighting and extinguishing of fires. Yet, very soon after those first electric lights switched on, the memory of fire-based illumination was snuffed out.

Archaeology and Egyptology both developed alongside lighting devices throughout the 1800s. Scholarly giants of early Egyptology, such as William Matthew Flinders Petrie, Karl Richard Lepsius, James Henry Breasted, and others lived through the lighting revolution. While they no doubt marveled at this technological innovation initially, they likely soon grew accustomed to electric illumination. As artificial light became more common throughout the 1900s, it faded further into the background of daily life. The majority of our lives today take place under artificial lighting, but we hardly give it a second thought. The modern ubiquity of light has also bled over into scholarly exploration of the ancient world. Egyptologists, for example, have largely given little thought to lighting technology in ancient Egypt. As a result of all this, Egyptology has a bit of a lighting problem. More specifically, how the ancient Egyptians lit their world is a topic relatively undiscussed, and underexplored, in Egyptology. This gap in our understanding appears to be a symptom of a deeper issue within studies of the ancient Near East and Mediterranean. Artificial light, a man-made source of illumination, is seldom directly addressed in archaeological research. This is surprising not only because artificial lighting is one of the earliest tools used by humans but also because it impacts on so many areas of life. The first use of artificial light, for instance, correlates to the first time that humans made fire. Very early fires may have served as a means of cooking and heat but they also provided illumination. By the time humans began to paint the cave walls of Lascaux, Chauvet, and Altamira, lighting implements were produced with the express purpose of serving as a light source. These were simple in construction, requiring an illuminant, a fat or oil, and a wick, such as a strip of fabric or a piece of reed or wood. If a wick and illuminant are placed in a vessel, the device is called a lamp in modern vernacular. Alternatively, the wick could be coated in illuminant to create an implement that could be placed upright in a holder or held in the hand. These light sources are given a variety of names including torch, taper, and candle. While basic in form, artificial lights can provide a great deal of information about the ancient world.